The 19th century was a time of political revolution, national unification, and cultural renewal in Italy. Among the many voices who contributed to this exciting period of literary and political transformation was the Italian poet Felice Cavallotti, a man equally known for his pen and his politics. Born in 1842, Cavallotti stood out among the 19th century Italian poets not only for his literary output but also for his passionate involvement in national affairs. His served poetry both artistic and civic functions, reflecting the ideals of liberty, unity, and moral duty that defined the Risorgimento era.

This article explores Cavallotti’s role within the broader movement of 19th century Italian poetry. It examines his themes, style, influence, and compares him to other poets of his generation. In doing so, it places Cavallotti within the continuum of literary history while highlighting the unique elements of his voice. As we analyze his work, we also understand how Italian poetry of the 1800s evolved alongside Italy’s dramatic political changes.

Early Life and Political Foundations

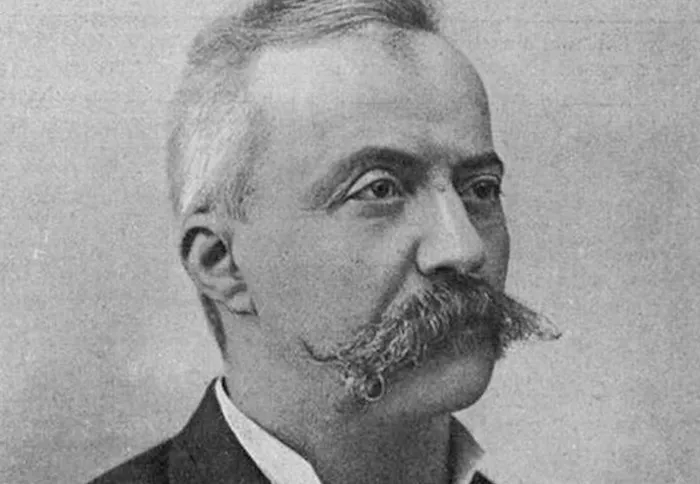

Felice Carlo Emanuele Cavallotti was born in Milan in 1842, during a time when the Italian peninsula was divided among foreign powers and regional states. As a young man, he developed a deep interest in literature and patriotism. These two passions shaped the rest of his life. Cavallotti believed in the power of the written word to influence hearts and minds, and his early exposure to liberal and nationalist ideals would define his poetic career.

Like many 19th century Italian poets, Cavallotti was heavily influenced by the spirit of the Risorgimento—the movement for the unification of Italy. However, unlike some contemporaries who focused mainly on aesthetic matters, he treated poetry as a means of activism. He believed that poetry should be useful to society, a view rooted in classical traditions but sharpened by his political engagement.

Cavallotti’s Poetic Vision

As an Italian poet, Cavallotti aimed to bridge the gap between poetic expression and political action. His works are often direct, passionate, and infused with moral fervor. He did not write primarily for the literary elite, but for the people, the citizens, and the patriots. His verse often dealt with themes such as justice, freedom, civil responsibility, and anti-clericalism.

His poetry was marked by rhetorical strength rather than delicate lyricism. While some of his contemporaries, such as Giosuè Carducci, sought to revive classical forms with refined poetic language, Cavallotti preferred accessible diction and clear structure. He employed poetry as a political weapon, a means to mobilize and awaken the masses.

Literary and Political Duality

Cavallotti was a man of letters and a man of action. He served as a member of the Italian Parliament and became a leading figure of the Radical Party. His speeches in Parliament often mirrored the tone and conviction of his poetry—incisive, impassioned, and uncompromising. He opposed corruption, the monarchy’s overreach, and the privileges of the Church. His criticism of the clerical establishment was particularly bold, and it earned him many enemies as well as admirers.

In this sense, Cavallotti was similar to other 19th century literary figures who crossed the boundary between poetry and politics. However, what made him unique was the consistency of his message. Whether speaking from the chamber or writing for the public, he voiced the same ideals. His poetry did not seek personal beauty or introspection, but communal awakening.

Themes in Cavallotti’s Poetry

One of the strongest elements in Cavallotti’s poetry is his use of satire. He exposed the hypocrisies of political and religious figures with biting wit. Satirical poetry had long roots in Italian literature, but Cavallotti gave it a modern political edge. His targets were not abstract vices but real institutions and individuals who he believed betrayed the people’s trust.

He also wrote elegies and tributes to freedom fighters and martyrs of the unification cause. His admiration for Giuseppe Garibaldi was especially deep. In such poems, he used a more solemn tone, combining patriotic pride with sorrow for those who died for the Italian dream.

Occasionally, he also explored personal themes, such as love and friendship, though these works remain less known. Even in these poems, however, one finds his moral sense. He was not interested in sensual or romantic excess but in idealized relationships rooted in respect and shared values.

Cavallotti and the Tradition of Italian Poetry

To better understand Cavallotti’s place in the literary canon, it is useful to compare him with other 19th century Italian poets. Giosuè Carducci (1835–1907), the first Italian Nobel laureate in literature, is perhaps the most notable of his peers. Carducci shared Cavallotti’s political views, especially his anti-clerical stance, but he expressed them with a different aesthetic. Carducci’s poetry was more formal, more concerned with poetic structure and classical references.

Another contemporary was Aleardo Aleardi, a poet with romantic sensibilities who focused more on nature, love, and melancholic reflection. Aleardi, like many romantic poets, saw poetry as a personal experience. In contrast, Cavallotti saw poetry as a public service.

Gabriele D’Annunzio, although a younger generation, began publishing in the later years of Cavallotti’s life. D’Annunzio brought a decadent and aesthetic style that contrasted sharply with Cavallotti’s moralistic tone. Where D’Annunzio sought beauty and sensation, Cavallotti sought truth and justice.

These comparisons show that Cavallotti occupied a particular niche within 19th century Italian poetry—one where ethics, politics, and social reform outweighed stylistic elegance. He was a civic poet in the purest sense.

Language and Style

Cavallotti’s language was direct and forceful. He used rhythm and meter to emphasize his arguments rather than for musicality. His verse often reads like an oration, filled with rhetorical questions, exclamations, and calls to action. This style was well-suited to the times, especially in post-unification Italy where political consciousness was rising.

Unlike more romantic poets, Cavallotti avoided abstract metaphors or symbolic landscapes. Instead, he described real events and real people. His poetry served as documentation of his age, giving voice to democratic values and public conscience.

Legacy and Later Influence

Although not as widely studied today as some of his contemporaries, Cavallotti remains an important figure in the history of Italian poetry. His legacy is particularly strong in the realm of political literature. He showed that poetry could be a weapon for justice and a tool for civic engagement.

After his death in 1898, Cavallotti was honored as a patriot and intellectual. Streets and schools were named after him. His collected works were published, and his political writings continued to influence liberal thought in early 20th century Italy.

His influence can also be seen in the work of poets and writers who believe in literature’s capacity to engage with public life. In today’s world, where the boundary between art and activism is often blurred, Cavallotti’s example feels timely.

Conclusion

Felice Cavallotti was not the most stylistically refined of the 19th century Italian poets, but he was among the most committed. As an Italian poet of the Risorgimento and post-unification era, he gave voice to the hopes and frustrations of a people striving for justice and national dignity. His poetry speaks less to the heart than to the conscience, but it remains vital in its honesty and urgency.

Italian poetry in the 19th century was marked by diversity—romanticism, neoclassicism, early modernism, and political realism all flourished. In this rich mosaic, Cavallotti’s voice stands out for its courage, moral clarity, and unwavering belief in the power of words to shape society. He reminds us that poetry is not only an art of beauty but also an instrument of truth.

For students, scholars, and readers interested in the relationship between literature and public life, Cavallotti provides a valuable model. His life and works form a bridge between classical oratory and modern civic poetry, between the ideals of the past and the challenges of the present.