André du Bouchet stands as one of the most original voices in 20th Century French poetry. A poet of great intellectual rigor, he combined a deep philosophical awareness with a striking sensitivity to the material presence of language. His works, often minimalistic and spatially experimental, reflect a concern with perception, silence, and the natural world. As a 20th Century French poet, du Bouchet diverged from lyrical traditions and embraced a poetics rooted in fragmentation, openness, and the autonomy of the poetic word. His contributions not only shaped modern French poetry but also placed him in dialogue with fellow innovators such as Paul Celan, Yves Bonnefoy, and René Char.

This article explores du Bouchet’s poetic vision, his philosophical and aesthetic foundations, and his place among the foremost 20th Century French poets. Through comparisons and contextual analysis, we aim to understand his unique contribution to French poetry and how his work continues to influence readers and writers today.

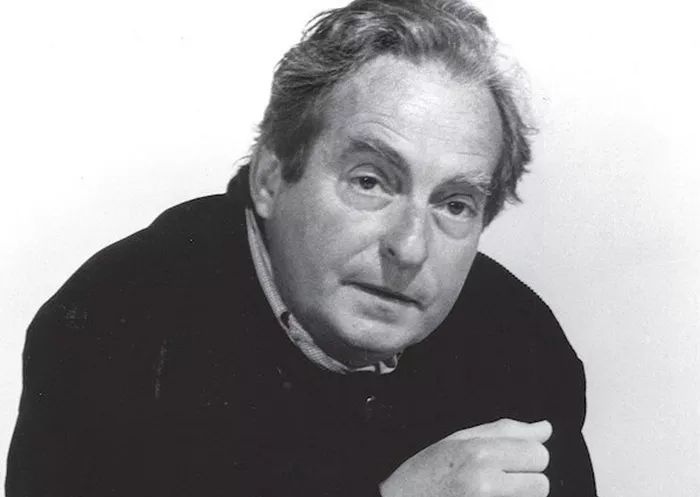

André du Bouchet

André du Bouchet was born on March 7, 1924, in Paris, France. He spent much of his youth between France and the United States, which gave him a bilingual and bicultural education. His experiences abroad offered him a broader perspective on literature and language, which later became evident in the experimental nature of his poetry.

Du Bouchet studied literature and philosophy at institutions such as Amherst College and Harvard University before returning to France, where he completed his education at the Sorbonne. He was influenced by major literary figures, especially those from the French and German traditions. Writers like Stéphane Mallarmé, Arthur Rimbaud, Friedrich Hölderlin, and Paul Valéry shaped his early literary inclinations.

This intellectual background laid the groundwork for his poetic style: fragmented, abstract, and often difficult. Yet within this complexity, there was always a desire to reach for the elemental, the physical, and the real. As a French poet trained in both the classical and modernist traditions, du Bouchet became an interpreter of the world through the medium of sparse and challenging verse.

The Emergence of a Distinct Poetic Voice

Du Bouchet began to publish poetry in the 1950s. His first major collection, Le Moteur blanc (1956), already displayed the features that would characterize his mature work. His language was stripped-down and open. He used blank spaces, fragmentation, and silences as integral components of his poetic structure.

Unlike many of his contemporaries who leaned toward narrative or lyrical expression, du Bouchet focused on the act of perception itself. In this sense, he was more aligned with phenomenology than with traditional poetic sentimentality. His poems are landscapes of thought, not only in subject but also in form.

Du Bouchet described poetry not as a mirror of reality but as a space of encounter, where language meets the world in a raw and unfiltered way. This concept of poetry as a terrain aligns him with another major 20th Century French poet, Yves Bonnefoy, who also emphasized presence and the materiality of language. However, while Bonnefoy’s verse often seeks reconciliation and unity, du Bouchet’s poems resist closure. They remain open, unresolved, and searching.

Poetics of Space and Silence

One of the most significant aspects of du Bouchet’s poetry is his use of space. On the printed page, his poems often resemble visual art more than conventional verse. Words are scattered, isolated, or arranged with extreme precision. This spacing is not decorative but essential. It marks pauses, silences, and gaps in meaning.

For du Bouchet, the white space of the page is not empty. It is alive with potential. The void between words is as important as the words themselves. In this regard, he shares affinities with Stéphane Mallarmé, the 19th-century French poet whose Un coup de dés experimented with visual layout and open form. Yet du Bouchet’s use of space is more ascetic, more severe. It echoes the barren landscapes he often describes—deserts, stones, windswept plains.

His minimalism recalls the haiku’s brevity, but it serves a different purpose. Whereas haiku distills a moment into three lines, du Bouchet’s verse unfolds absence and expands into silence. He does not offer epiphanies but invitations to dwell within unknowing.

Nature and the Elemental World

Du Bouchet’s poetry is filled with images of nature: rock, wind, sky, fire, earth. Yet these are not pastoral images. They are elemental—reduced to their most basic form. He is not interested in nature as scenery but as a force.

This approach aligns him with another 20th Century French poet, René Char. Both poets evoke nature in austere and sometimes violent terms. But while Char’s landscapes often carry a mythic or symbolic weight, du Bouchet’s are more immediate and literal. A stone is a stone. Wind is wind.

He resists metaphor in favor of the thing itself.

Such poetic materialism echoes phenomenological philosophy, particularly the work of Maurice Merleau-Ponty, who emphasized embodied perception and the experience of space. Like Merleau-Ponty, du Bouchet is concerned with how we encounter the world, not merely what we see in it.

Language as Resistance

Du Bouchet’s poetry resists easy interpretation. It is not narrative or didactic. There are few confessions, few stories, and little ornament. His language is rough, jagged, broken—a mirror of the world’s difficulty and the limitations of expression.

He once wrote: “The poem does not describe. It presents.” This statement reflects his conviction that poetry should not explain the world but enact an encounter with it. Language is not a tool for representing reality but a space where the self meets the external world.

This philosophy separates him from other 20th Century French poets like Paul Éluard or Louis Aragon, whose surrealist aesthetics emphasized imaginative transformation. While du Bouchet admired their creativity, he pursued a different kind of truth—one rooted in wordlessness, materiality, and rupture.

Collaborative and Editorial Work

In addition to writing poetry, du Bouchet was a translator, editor, and essayist. He translated works by Paul Celan, Osip Mandelstam, and William Faulkner. His translations reveal his sensitivity to the weight and rhythm of language across cultures.

He also founded and co-edited literary journals such as L’Éphémère, which became a central platform for avant-garde French poetry in the 1960s and 70s. Alongside Yves Bonnefoy, Jacques Dupin, and Paul Celan, du Bouchet used the journal to promote a poetry of openness, resistance, and formal innovation.

These editorial and collaborative roles placed du Bouchet at the heart of modern French poetry. His influence extended beyond his own writing to shape the critical and aesthetic discourse of his time.

Comparison with Paul Celan and Yves Bonnefoy

To better understand du Bouchet’s place in 20th Century French poetry, it is useful to compare him with two peers: Paul Celan and Yves Bonnefoy.

Paul Celan, though born in Romania and writing in German, became deeply integrated into the French poetic scene. Like du Bouchet, Celan’s work grapples with silence and the limits of language. Both poets use fragmentation and spatial arrangement to create meaning beyond syntax.

However, Celan’s work is haunted by the trauma of the Holocaust, and his poems often carry a political or historical weight absent from du Bouchet’s more abstract verse. Celan’s silence is tragic; du Bouchet’s is elemental.

Yves Bonnefoy, on the other hand, shares more thematic ground with du Bouchet. Both seek presence, materiality, and immediacy. Yet Bonnefoy’s poems are more meditative and accessible. His language seeks to clarify; du Bouchet’s to dislocate.

These differences highlight the diversity within 20th Century French poetry. Du Bouchet was not isolated but part of a vibrant and experimental tradition that redefined the possibilities of poetic form.

Critical Reception and Legacy

Du Bouchet’s poetry was never widely popular, but it has been highly influential among poets, critics, and philosophers. He was awarded the Grand Prix de Poésie by the French Academy in 1983, a recognition of his importance in French letters.

His work has been studied for its philosophical implications, its aesthetic rigor, and its contribution to modernist poetics. Scholars have linked his poetics to Heidegger, Merleau-Ponty, and other existential thinkers. Artists and musicians have also drawn inspiration from his spatial and rhythmic innovations.

In contemporary French poetry, his influence endures. Poets continue to explore silence, fragmentation, and the elemental—echoes of du Bouchet’s trailblazing vision. His legacy is not one of imitation but of invitation—to rethink what poetry is and what it can do.

Conclusion

André du Bouchet is a central figure in 20th Century French poetry. His works challenge the reader to abandon conventional expectations and to engage language as a field of perception. As a French poet, he forged a path that diverged from lyricism and embraced an austere, elemental beauty.

His poetry is not easy, but it is rewarding. It invites contemplation, disorientation, and rediscovery. Among 20th Century French poets, du Bouchet occupies a unique place—a poet of silence, stone, and space, whose words carry the force of the world itself.

For those seeking a deeper understanding of modern French poetry, du Bouchet offers not answers, but a voice that listens to the silence between things.