Jean Sénac occupies a unique and poignant place in the history of 20th Century French poetry. As a French poet born in Algeria, he wrote at the intersection of cultures, identities, and conflicts. His life and work were shaped by colonial tensions, questions of national identity, and a deeply personal struggle for self-expression. Sénac was a marginalized voice who became a symbol of defiance and artistic authenticity in a politically charged era.

This article will examine the life, poetic vision, and lasting contribution of Jean Sénac. It will explore his style, themes, and position within the broader field of French poetry. It will also offer comparisons with other major 20th Century French poets, such as René Char, Paul Éluard, and Aimé Césaire. Through this examination, we aim to understand how Sénac transformed personal and political conflict into poetic power.

Jean Sénac

Jean Sénac was born on November 29, 1926, in Béni Saf, Algeria, then a French colony. His exact parentage is unclear, and he was raised in poverty by his single mother. These beginnings deeply influenced his worldview. He was both part of the French-speaking elite and excluded from traditional French identity because of his social class and his birth outside of metropolitan France.

The young Sénac found refuge in literature. French poetry became his medium for understanding the world. Early on, he admired Arthur Rimbaud, whose rebellion, sensuality, and mysticism would echo throughout Sénac’s writing. The adolescent poet also engaged with the surrealist and symbolist traditions of French poetry, as well as the revolutionary writings of poets like Paul Éluard.

Sénac’s early poems already reflected a fusion of personal yearning and political sensitivity. His identity as both Algerian and French, and as a homosexual man in a repressive society, made him aware of multiple forms of marginalization. His early literary promise was soon recognized, and he began corresponding with major literary figures, including Albert Camus.

Relationship with Albert Camus: A Complicated Brotherhood

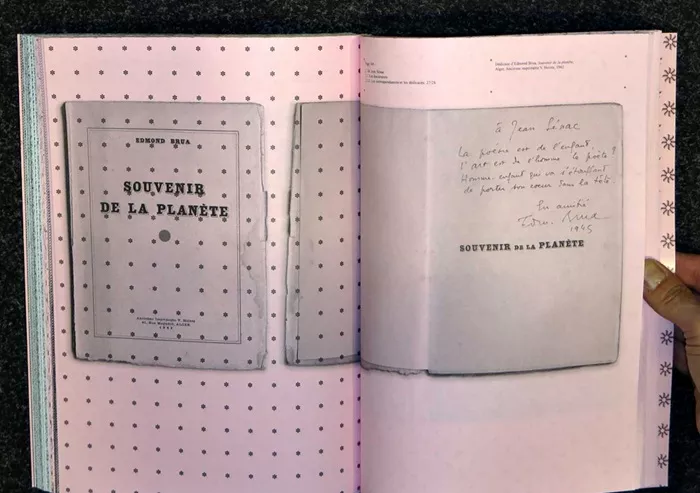

One of the most important early influences on Sénac’s career was Albert Camus. The two writers shared similar backgrounds as poor, French-speaking Algerians with deep political concerns. Camus encouraged Sénac and even helped publish his first poems in L’Arche, a French literary journal.

However, the friendship soured during the Algerian War of Independence (1954–1962). Camus advocated for moderation and coexistence between Algerians and the French, while Sénac became an outspoken supporter of Algerian independence. He identified with the Algerian national struggle, not as a nationalist, but as a humanist and poet committed to justice.

Sénac felt betrayed by Camus’s silence in the face of French colonial violence. He saw poetry not as a retreat from politics, but as a weapon of resistance. His break with Camus symbolized a larger break with the French intellectual establishment, which often failed to confront the moral implications of colonialism.

The Algerian War and the Poet of the Revolution

The Algerian War was the defining moment in Sénac’s life. As a 20th Century French poet, he faced the painful task of reconciling his French language and heritage with his support for the Algerian cause. He refused to leave Algeria and chose to identify himself as an Algerian poet writing in French.

During the war, he published fiery, lyrical collections such as Avant-Corps and Matinale de mon peuple. These works fused eroticism with political defiance. He wrote about the suffering of the Algerian people, the need for revolution, and the intimate pain of being torn between worlds.

One of Sénac’s most powerful poetic strategies was the blending of public and private themes. His poems celebrated male beauty and homosexual desire, while also invoking revolutionary fervor. This combination of sensual and political language was unique in 20th Century French poetry and made him a radical voice in both aesthetic and political terms.

He did not merely speak for Algeria’s independence—he envisioned a new, plural, liberated society. In his poem “Le Soleil sous les armes” (The Sun Under Arms), Sénac wrote:

“Nous bâtirons un pays de feu / Où l’homme ne soit plus humilié.”

(“We will build a land of fire / Where man will no longer be humiliated.”)

A French Poet in Postcolonial Algeria

After independence in 1962, Sénac chose to stay in Algeria, even though he was now a minority in a country redefining its national identity. He became a tireless cultural promoter. He organized poetry readings, literary salons, and radio programs. He supported young Algerian writers and tried to create a modern Algerian literature in French.

However, Sénac remained an outsider. His homosexuality, atheism, and continued use of the French language made him a controversial figure. While he supported the revolutionary ideals of the new Algeria, he also criticized its authoritarian tendencies. He envisioned Algeria not as an Arab-Muslim state, but as a diverse society based on human dignity and creativity.

His post-independence works, such as Poèmes Iliaques and Le Soleil sous les armes, continued to explore themes of exile, desire, and resistance. His voice became increasingly solitary, but never resigned. As a 20th Century French poet, he carved a space for radical authenticity in a time of political dogma and cultural pressure.

Poetic Style and Themes: Eros, Fire, and Identity

Jean Sénac’s poetry is characterized by emotional intensity, sensual imagery, and political urgency. He wrote in free verse, often using short, incantatory lines. His language is direct but also rich in metaphors. Fire, sun, body, and wound are recurring motifs.

Sénac’s central themes include:

Eros and the body: Sénac was one of the few openly gay French poets of his time. He celebrated male beauty and sexual desire without apology. His poems are filled with images of youth, skin, heat, and longing.

Revolution and justice: He believed poetry should not remain neutral in the face of oppression. His writing bears witness to the violence of colonialism and the hope of liberation.

Alienation and exile: As a poet between cultures and identities, Sénac often wrote about loneliness, betrayal, and the search for belonging.

Sun and fire: The Algerian sun is a central metaphor in his work. It represents both erotic warmth and revolutionary energy. Fire becomes a symbol of purification, passion, and resistance.

His style is both lyrical and confrontational. He merges the sensual and the political in ways that challenge conventional categories of French poetry. His poetry is visceral, honest, and urgent.

Comparison with Other 20th Century French Poets

Jean Sénac’s work can be better understood when placed in the context of other major figures of 20th Century French poetry.

Paul Éluard: Like Sénac, Éluard believed in the political power of poetry. Both were associated with the resistance. However, while Éluard remained closer to surrealism, Sénac’s style was more corporeal and passionate.

René Char: Char also engaged with political resistance, particularly during World War II. He and Sénac shared an interest in poetry as a form of ethical action. Char’s style, though, is more abstract and philosophical. Sénac was more visceral.

Aimé Césaire: The comparison with Césaire is particularly fruitful. Both poets wrote from colonized spaces and struggled with questions of language and identity. Both used the French language to challenge French domination. However, while Césaire embraced the Black consciousness of Négritude, Sénac embraced a broader vision of human liberation that was less bound to racial identity.

Jean Genet: Genet’s homoerotic and politically radical texts share a deep affinity with Sénac’s poetry. Both foregrounded marginal identities and celebrated transgression.

Sénac thus belongs to a unique strand of 20th Century French poetry that merges aesthetic beauty with moral resistance. His voice resonates with the rebellious spirit of Rimbaud, the ethical fire of Char, and the cultural defiance of Césaire.

The Tragic End: Death and Legacy

Jean Sénac was murdered in Algiers on August 30, 1973. The circumstances of his death remain mysterious. He was found naked and stabbed in his apartment. No one was ever arrested. The murder may have been linked to his sexuality, his political views, or his public presence in a still-conservative society.

His death was a tragedy, but also a symbol. Sénac had lived and died as a poet of truth. His life was a continuous act of poetic resistance—against colonialism, homophobia, repression, and indifference.

In the decades since his death, Jean Sénac has become a cult figure. His work has been studied by scholars of French poetry, postcolonial literature, and queer theory. He remains a key figure for those interested in how poetry can express the pain and beauty of cultural hybridity.

Influence and Reception: A Voice for the Marginalized

Though not as widely read as some of his contemporaries, Jean Sénac’s influence continues to grow. He anticipated many of the themes that would later dominate postcolonial and queer literature. His insistence on writing from the margins gave his work a prophetic quality.

His collected works have been published in several volumes, and his letters with Albert Camus provide insight into the literary politics of the era. His poetry has been translated into several languages. Scholars increasingly see him as an essential figure for understanding both 20th Century French poetry and the literature of decolonization.

Younger Algerian and Francophone poets now cite Sénac as a key influence. His courage, clarity, and sensuality offer a model for writing that refuses to compromise. He taught that French poetry could be written from the desert as well as the metropolis, from the body as well as the mind.

Conclusion

Jean Sénac is a vital yet often overlooked 20th Century French poet. His work stands at the crossroads of many identities—French and Algerian, poet and revolutionary, lover and exile. His poems burn with passion, resistance, and longing.

In the canon of French poetry, he challenges the dominance of purely metropolitan voices. He reminds us that the French language was not just spoken in Paris, but also in Algiers, Oran, and Béni Saf. He wrote with the conviction that poetry could change the world—and that it must speak the truth of the body, the people, and the oppressed.

For readers and scholars of French poetry, Jean Sénac offers a powerful example of how beauty and justice can converge. His life and work remain a radiant testament to the power of words to transcend borders and ignite hope.