The 20th century was a transformative period for Japanese literature. During this time, Japan underwent rapid modernization, two world wars, cultural reconstruction, and deep philosophical questioning. Among the voices that emerged during this complex century was the Japanese poet Genyoshi Kadokawa, born in 1917. Though less internationally known than some of his contemporaries, Kadokawa played a quiet but significant role in the landscape of 20th century Japanese poetry. His work, rooted in classical tradition yet aware of modern discontent, provides insight into a changing nation and a poetic identity in flux.

This article explores Kadokawa’s contribution within the broader tapestry of 20th century Japanese poets. It compares his work with that of his contemporaries, examines the historical and literary contexts of his writing, and considers the unique qualities that define his poetry. In doing so, it aims to offer a portrait not only of the man himself but of the evolution of Japanese poetry across a century of profound change.

The Emergence of a Poet in a Transitional Era

Genyoshi Kadokawa was born in 1917, during the Taishō era (1912–1926), a short but culturally rich period marked by democratic movements and a flourishing of the arts. As Kadokawa grew into his literary voice, Japan entered the Shōwa era (1926–1989), which spanned militarism, war, defeat, and rebirth. His poetic development coincided with Japan’s tumultuous transition from empire to pacifist democracy. These changes deeply influenced the work of many 20th century Japanese poets, including Kadokawa.

Kadokawa’s poetry reflects both a reverence for traditional Japanese poetic forms, such as waka and haiku, and a keen awareness of modern anxieties. This duality—bridging the classical and the modern—characterizes much of 20th century Japanese poetry. It is this tension that gives Kadokawa’s poetry a distinctive voice: neither purely nostalgic nor entirely modernist, but a negotiation between the two.

Literary Influences and Style

Kadokawa was influenced by both the classical Japanese canon and modern literary movements. He admired poets from the Heian period, such as Ki no Tsurayuki and Murasaki Shikibu, whose aesthetics of refined emotional expression shaped early Japanese poetry. At the same time, Kadokawa was attentive to the avant-garde experimentation that defined much of 20th century literature in Japan and abroad.

His poetic style often blends simplicity with subtle philosophical depth. He preferred clarity over ornamentation, and emotional sincerity over abstraction. This places him in contrast with contemporaries like Shūji Terayama (1935–1983), whose experimental and surrealist approach often challenged conventional forms. Kadokawa, by contrast, remained closer to the lyrical traditions, although he did so with a voice that recognized the chaos of modern life.

Comparison with Contemporaries

To understand Kadokawa’s place in Japanese poetry, it is helpful to compare him with other 20th century Japanese poets such as Kenji Miyazawa (1896–1933), Yosano Akiko (1878–1942), and Sakutarō Hagiwara (1886–1942).

Kenji Miyazawa was a devout Buddhist and agrarian who wrote deeply spiritual poetry. His work, filled with nature imagery and mystical themes, presents a cosmic view of human suffering and redemption. While Kadokawa shared an appreciation for nature, his tone was more restrained and introspective.

Yosano Akiko, one of the most influential female poets of the era, brought passion and sensuality into the traditional tanka form. Her poetry challenged social norms, especially regarding gender and personal freedom. Kadokawa, on the other hand, was more conservative in form and tone, but no less reflective. Where Yosano’s voice was fiery and progressive, Kadokawa’s was quiet and contemplative.

Sakutarō Hagiwara revolutionized modern Japanese poetry with his free verse and psychological depth. Often considered the father of modern Japanese poetry, Hagiwara broke with classical form entirely. Kadokawa did not pursue this radical break, but he did adapt and evolve traditional forms to suit contemporary themes.

Through these comparisons, we see that Kadokawa occupied a middle ground—neither a traditionalist in the rigid sense, nor a radical. His contribution lies in how he preserved classical beauty while responding to modern life.

Themes in Kadokawa’s Poetry

Kadokawa’s poetry often centers on impermanence, solitude, memory, and nature. Like many Japanese poets, he was deeply influenced by the concept of mono no aware—an awareness of the impermanence of things and a gentle, melancholic acceptance of that transience.

His verses often evoke quiet landscapes: falling leaves, fading blossoms, morning mist. These natural images are not merely decorative; they mirror internal emotional states and philosophical reflections. Kadokawa’s sensitivity to the seasons, a long-standing feature of Japanese poetry, becomes a means to explore broader human concerns—loss, aging, change, and continuity.

Another key theme in Kadokawa’s work is historical memory. Living through World War II and its aftermath, Kadokawa—like many 20th century Japanese poets—could not avoid the imprint of war. Yet, unlike poets such as Tamura Ryūichi (1923–1998), whose poetry confronted postwar disillusionment with stark realism, Kadokawa trauma addressed with subtle, symbolic language. His reflections on loss are indirect, yet deeply moving.

Language and Form

Kadokawa’s language is notable for its simplicity and elegance. He avoided ornate expressions, favoring clean diction and careful rhythm. His poetry often uses traditional forms—particularly tanka, the 31-syllable form that has been a staple of Japanese poetry for over a thousand years. However, he was not averse to experimenting within these forms, bringing fresh nuance to well-worn patterns.

In this respect, Kadokawa’s work shares similarities with Masaoka Shiki (1867–1902), who revitalized the haiku and tanka in the Meiji period. Shiki had argued for a more realistic and less formulaic poetry, and Kadokawa carried this spirit forward, albeit in a more emotionally introspective direction.

While Kadokawa did not write much in free verse, he did incorporate modern imagery and contemporary themes into classical structures. This synthesis is part of what defines 20th century Japanese poetry: a continuous dialogue between the past and the present.

The Kadokawa Legacy

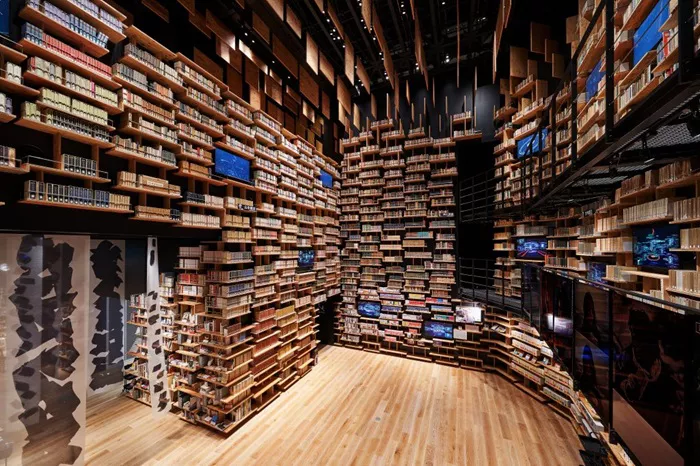

Genyoshi Kadokawa’s poetic career was also connected to the world of publishing. He was part of the family behind Kadokawa Shoten, one of Japan’s most prominent publishing houses. This gave him both access to literary networks and a platform for promoting poetic voices. His editorial and literary judgment helped shape Japanese poetry and literature during the postwar years.

While Kadokawa did not gain the fame of some of his peers, his work influenced a generation of poets who sought to maintain cultural continuity in the face of rapid modernization. His poetry offers a model for how to remain rooted in tradition while engaging with the complexities of the present.

Today, Japanese poetry continues to evolve, influenced by global literary trends, digital culture, and shifting social values. Yet, the foundation laid by poets like Kadokawa remains vital. His poetry reminds us that form, restraint, and quiet reflection still have power in an age of noise and fragmentation.

Conclusion

Genyoshi Kadokawa represents a key thread in the fabric of 20th century Japanese poetry. He is a poet who honors tradition but does not cling to it. He speaks with a voice that is calm yet perceptive, nostalgic yet aware of the present.

In comparing Kadokawa with poets like Yosano Akiko, Kenji Miyazawa, and Sakutarō Hagiwara, we see the rich diversity of Japanese poetic responses to the 20th century. Some poets turned to surrealism, others to romantic rebellion, and still others, like Kadokawa, to the reflective discipline of classical forms reimagined for modern life.

His legacy is not just in the poems he wrote, but in the example he set for how a Japanese poet can balance the weight of tradition with the urgency of the present. For readers today, his work offers both beauty and wisdom—qualities that remain essential in any era.

In studying Genyoshi Kadokawa, we gain more than insight into a single life; we glimpse the broader story of Japanese poetry as it moved through a century of conflict, change, and renewal.