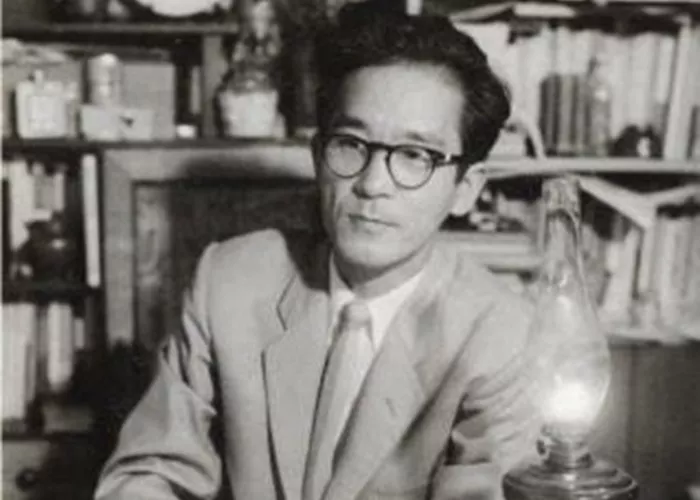

Among the most quietly influential voices in modern literature, the Japanese poet Yūji Kinoshita, born in 1914, made a lasting impression on the poetic landscape of Japan in the 20th century. His work emerged at a time of political upheaval, cultural realignment, and artistic reinvention. poets. His poetry, filled with natural imagery and subdued introspection, offers a compelling lens into the postwar Japanese psyche. This article explores Kinoshita’s life and literary contributions, placing him within the broader currents of Japanese poetry and alongside his poetic peers.

Historical and Cultural Context

To understand the importance of Yūji Kinoshita, it is essential to first grasp the turbulent backdrop of his era. Born just before the Taishō period (1912–1926), he witnessed Japan’s imperial expansion, World War II, and the country’s subsequent defeat and occupation. These events deeply shaped Japanese poets of his generation. The transition from prewar militarism to postwar pacifism created a rich but troubled environment for the arts. Writers and artists responded in various ways—some turning to surrealism, others to political commentary, and some, like Kinoshita, to quiet reflection.

The war had destroyed much of Japan physically and emotionally. The 1950s and 1960s saw a cultural shift marked by reevaluation and reinvention. In this landscape, Japanese poetry played a crucial role in helping people articulate trauma, rebuild identity, and reimagine their future. While many embraced modernist or avant-garde forms, others, including Kinoshita, looked to nature, memory, and classical aesthetics for solace and meaning.

Yūji Kinoshita’s Life and Literary Path

Yūji Kinoshita was born in Hiroshima Prefecture in 1914. Trained as a schoolteacher, he spent much of his life working in education. His connection to the land and to ordinary life informed the imagery of his poems. He did not seek fame or literary prestige, which perhaps explains his modest place in the canon despite his high artistic quality.

Kinoshita began publishing his poetry in the 1940s, but his reputation grew mostly in the postwar years. He wrote in a voice that was contemplative, deeply rooted in nature, and often melancholic. His work draws upon traditional Japanese poetry forms, such as tanka and haiku, but he adapted them into free verse and longer lyric poems suitable for modern readers. His use of seasonal imagery, especially the changing of leaves or the quiet presence of rivers, connects his poetry to centuries of Japanese literary tradition.

Themes in Kinoshita’s Work

Nature plays a central role in Kinoshita’s writing. However, unlike poets of earlier eras who celebrated nature’s beauty, Kinoshita often used natural imagery to express loss, silence, and solitude. This reflects the influence of the postwar atmosphere, where beauty was often mingled with grief.

One of his most frequently cited poems includes the image of a withered branch against a winter sky. The starkness of the image speaks to emotional barrenness but also to endurance. Many of his poems similarly emphasize survival through bleak seasons, both literal and metaphorical.

Kinoshita also explores the inner emotional life with restraint and dignity. His poems do not shout; they whisper. In a poem about his brother lost in the war, Kinoshita writes with minimal detail, allowing silence to carry the weight of sorrow. This technique—letting absence speak—became one of his hallmarks.

Comparison with Other 20th Century Japanese Poets

To appreciate Kinoshita’s unique voice, it is helpful to compare him with other 20th century Japanese poets. His near contemporary, Shūji Terayama (1935–1983), adopted a radically different approach. Terayama’s poetry was flamboyant, theatrical, and rebellious. He experimented with language, performance, and social taboos, becoming a symbol of the 1960s counterculture. Kinoshita, by contrast, preferred quiet reflection and traditional forms.

Another relevant comparison is with Nobuo Ayukawa (1920–1986), a poet deeply marked by wartime experiences. Ayukawa wrote with existential dread and intellectual depth, often influenced by Western philosophy. While Kinoshita also experienced the war’s trauma, his response was more lyrical and rooted in the Japanese landscape rather than abstract thought.

Junzaburō Nishiwaki (1894–1982) represents a bridge between Japanese and Western modernism. As a translator of T.S. Eliot and a leading modernist, Nishiwaki’s poetry shows technical experimentation and dense allusion. Kinoshita did not engage with foreign influence in the same overt way. His poetic world was smaller but more emotionally intimate.

Yet despite these differences, all these poets share a mission: to find language that could express a fractured reality. Whether through philosophical reflection, surreal drama, or natural imagery, Japanese poets of the 20th century sought to restore meaning in a time of loss.

Kinoshita’s Style and Language

Kinoshita’s language is deceptively simple. His sentences are often short, his metaphors clear. He avoids abstraction. The Japanese language, with its layered allusions and cultural references, lends itself to subtle expression. Kinoshita mastered this quality. He never used ten words where five would do.

One striking feature of his poetry is its rhythm. Even in free verse, Kinoshita maintained a gentle cadence, often echoing traditional meters. This gave his poems a meditative quality. Reading his work feels like walking slowly through a forest after rain—quiet, observant, and inward-looking.

In his later years, Kinoshita’s poetry became even more spare. Illness and aging crept into his themes. Yet he did not write with bitterness. Instead, he accepted impermanence, a key concept in Japanese aesthetics. In this way, he embodied the ideal of mono no aware, the awareness of life’s transience.

Legacy and Influence

While Kinoshita never achieved the international recognition of figures like Yukio Mishima or Kenzaburō Ōe, his influence on Japanese poetry is profound. Many younger poets cite him as a model of quiet excellence. His work reminds readers that deep emotion need not be loud, and that traditional forms can still hold modern truth.

Kinoshita’s poetry is also frequently anthologized in Japanese school curricula, particularly in the 1980s and 1990s. His straightforward language and emotional clarity make his poems accessible to younger readers while still offering layers of depth for mature interpretation.

Moreover, in the world of Japanese literary journals, his work continues to be discussed. His approach has influenced poets such as Hiromi Itō, who combines lyrical detail with emotional restraint, and Shuntarō Tanikawa, who values clarity and musicality.

Relevance Today

In the 21st century, Kinoshita’s poetry remains relevant. As the world faces environmental crisis, political instability, and emotional alienation, his quiet attention to nature and inner life offers a form of resistance. He does not provide answers but models a way of seeing—patient, attentive, and open.

Modern Japanese poets are once again turning to nature and simplicity. The digital age has brought speed and noise. In contrast, Kinoshita’s poems act like deep wells—still, dark, and nourishing.

Furthermore, the themes of grief, endurance, and impermanence have gained new resonance in a post-pandemic world. Many readers find comfort in his verses, which speak to the universality of sorrow and the possibility of beauty even in hardship.

Conclusion

Yūji Kinoshita, though not a household name outside of Japan, deserves his place among the significant 20th century Japanese poets. His work reflects the turmoil and transformation of his time while offering a deeply personal vision grounded in nature and quiet emotion. His poems are not declarations but meditations. In a century filled with noise, he wrote with silence. And in that silence, he found truth.

Through his clear-eyed attention to the small and the ordinary, Kinoshita enriched Japanese poetry. His legacy reminds us that restraint is not weakness, that grief can be dignified, and that poetry, at its best, connects us to what is most enduring in the human spirit.

In the landscape of 20th century literature, where many poets shouted to be heard, Yūji Kinoshita listened. And in listening, he taught us how to hear again.