ules Supervielle was a French poet whose work bridged the classical and the modern. Born in 1884 and active through much of the twentieth century, he witnessed dramatic changes in literature and society. As a French poet, he turned his gaze toward both the inner self and the external world. His verse reflects a love of nature, a sense of wonder, and a lyrical clarity. In this article, we explore his life, his art, and his place in French poetry. We also compare him to other writers of his era. Through this, we gain insight into the evolution of the 20th Century French Poet.

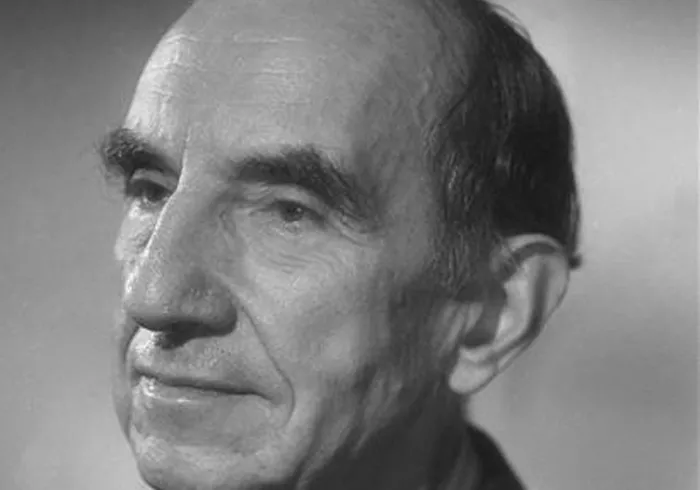

Jules Supervielle

Birth and Family

Jules Supervielle was born on January 16, 1884, in Montevideo, Uruguay. His father was a French engineer and his mother was Uruguayan. In 1895, the family moved to France. There, he studied in Bordeaux and Paris. This dual heritage shaped his view of the world. It gave him a sense of distance from Parisian life even as he became part of it.

Education and First Interests

He studied at the Lycée Michel-Montaigne in Bordeaux. He later attended the École des Chartes in Paris. This training in history and archives honed his attention to detail. He read widely in French classics and in world literature. He discovered Victor Hugo, Charles Baudelaire, and Paul Verlaine. He also read modern Spanish and Latin American writers. These influences fed into his own work.

Return to South America

After his studies, Supervielle traveled again to Uruguay and Argentina. He stayed in Montevideo and Rosario. He taught French literature at the French Lyceum. These years in South America deepened his love of the landscape. He absorbed the sounds of rivers, winds, and the pampas. Such images later found their way into his poems, bringing a distinct flavor to his French poetry.

Literary Career

First Publications

Supervielle began to publish from 1907 onward. His first volume, L’Homme de la pampa, appeared in 1917. It collected poems that blend memory, dream, and nature. His early style is simple yet evocative. He writes of the horizon, of morning light, and of the silent pulse of life. This debut marked him as a fresh voice among the 20th Century French Poet.

Interwar Period

During the 1920s, he published several key collections:

Gravitations (1925)

Le For intérieur (1921)

Abandons (1923)

In these books, he developed a philosophy of poetry. He saw verse as a space of freedom. He believed that words could carry the reader beyond everyday time. His themes include exile, memory, and the unity of all things. He often used short lines and clear images. This simplicity sets his work apart from more ornate styles.

The 1930s and Beyond

In the 1930s, Supervielle continued to write both poetry and prose. He published:

Rebellions (1939)

Né sous une étoile (1941)

He also wrote essays on literature. He taught at the Collège de France. He served in the French Resistance during World War II. After the war, he resumed his literary work with renewed vigor. His later collections include:

Placard (1955)

Jeunes saisons (1959)

He was elected to the Académie française in 1960. He held the seat until his death in 1960, at age 76.

Poetic Themes and Style

Nature and the Cosmos

Nature is central in Supervielle’s work. He often writes of rivers, skies, and winds. He sees the cosmos as a living whole. In Gravitations, he compares human emotion to the pull of planets. He writes simple clauses that evoke grandeur:

The river moves in silent turns.

The mind drifts, free as wind.

This clarity aligns him with the classical tradition in French poetry, yet his cosmic vision is modern.

Memory and Exile

Exile marks Supervielle’s life. Born abroad and living between continents, he felt a sense of displacement. His poems often recall childhood scenes in Uruguay:

I hear the horses on the plain.

Their hooves echo my lost home.

Memory becomes a refuge. It also becomes a source of questioning. He asks whether time can heal absence. These themes resonate with many 20th Century French Poet who lived through wars and migrations.

Dream and Reality

Supervielle believed in the power of the imagination. He saw poetry as a bridge between dream and reality. His style often shifts suddenly from concrete image to dreamlike reflection. For example, in Abandons, a simple scene of a garden turns into a meditation on eternity. This fluidity links him loosely to Surrealism. Yet he never fully embraces automatic writing or shocking images. His dream is gentle, lyrical, and rooted in nature.

Musicality and Form

His lines are often short. He uses enjambment and pauses to create a musical effect. Unlike some contemporaries, he does not experiment with free verse extremes. He stays close to a classical sense of meter and rhyme. Yet his rhythms feel modern. They reflect speech and thought in motion. As such, he embodies a middle path in French poetry: respectful of tradition but open to innovation.

Major Works

L’Homme de la pampa (1917)

This first collection lays the groundwork. It mixes memoir and meditation. Supervielle writes of the plains of Uruguay. He introduces his central motifs: horizon, wind, and the human longing for unity.

Le For intérieur (1921)

The title means “the inner strength.” Here, he explores the self. He writes of solitude and the inner voice. He seeks a sense of wholeness that transcends earthly bonds.

Abandons (1923)

In Abandons, he abandons strict form. He allows the poem to flow. The collection shows his maturing style: short lines, precise images, and open spaces.

Gravitations (1925)

This book cements his reputation. He uses cosmic imagery to reflect on human ties. The title suggests both attraction and weight. Love, memory, and nature all gravitate toward each other.

Rebellions (1939)

Here, Supervielle writes on resistance. He questions injustice and human cruelty. Yet his tone remains measured. He does not rail or rant. He reflects on the moral responsibilities of the poet.

Né sous une étoile (1941)

The title, “Born under a star,” evokes fate. He contemplates destiny and chance. The poems here show depth of reflection, born of wartime experience.

Late Collections

Placard (1955): pens small, luminous poems.

Jeunes saisons (1959): a final celebration of renewal.

These works reveal his consistent voice. They show no decline in clarity or richness.

Comparisons with Contemporaries

Guillaume Apollinaire (1880–1918)

Apollinaire was a pioneer of modernism and free verse. His poems break with classical form. Supervielle, by contrast, keeps more structure. Apollinaire’s images shock; Supervielle’s soothe. Both explore dream, but Apollinaire leaps into Surrealism. Supervielle stays grounded.

Paul Valéry (1871–1945)

Valéry is the philosopher-poet. His work is cerebral and precise. He writes long, intricate poems. Supervielle’s verse is shorter and more lyrical. Yet both value clarity and musicality. Both aim to unify mind and world through poetry.

André Breton (1896–1966)

Breton led the Surrealists. He prized chance and the unconscious. His manifestos advocated automatic writing. Supervielle admired dream but rejected Surrealist dogma. He sought harmony over shock. His allegiance was to humanism and nature.

Louis Aragon (1897–1982)

Aragon began with Surrealism before joining the Communist Party. His later work became political. Supervielle remained personal and philosophical. Yet both wrote during wartime. Both felt poetry must respond to history. Aragon’s tone is militant; Supervielle’s is contemplative.

René Char (1907–1988)

Char’s verse is terse and elemental. He wrote the Resistance poems. Supervielle also resisted oppression, but his style is more lyrical. Both share a love of nature. Both see poetry as a moral act.

Contributions to French Poetry

A Bridge Between Eras

Supervielle links nineteenth-century Romanticism and symbolist heritage with twentieth-century modernism. He respects form but welcomes new images. He writes as a French poet aware of past glories and future challenges.

Humanism and Universality

He emphasizes the unity of all beings. His verse speaks to readers across borders. His South American roots give him a global perspective unusual among his peers.

Nature as Teacher

He restores nature to a central place in poetry. In an age of urbanization and war, he reminds us of rivers, winds, and skies. His influence appears in later poets who seek ecological and spiritual themes.

Ethics of Poetry

Supervielle believed the poet has a duty to bear witness. He saw poetry as resistance to dehumanization. This stance influenced post-war writers who held similar convictions.

Role in Literary Institutions

As a member of the Académie française, he defended literature and language. He mentored younger writers. He edited journals. Through these roles, he shaped the course of French poetry.

Legacy and Influence

Influence on Later Poets

Later generations—such as Yves Bonnefoy and Jacques Dupin—admired Supervielle’s clarity and humanism. Many take from him the lesson that poetry can be both lucid and profound.

Translations and Global Reach

His work has been translated into English, Spanish, Japanese, and more. International readers discover a poet who transcends national boundaries.

Critical Reception

Critics highlight his moral depth and lyrical grace. They praise his unique voice amid the tumult of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Some fault him for lack of radical experimentation. Yet most agree his contribution is vital.

Commemorations

Festivals in Montevideo and Bordeaux honor his memory. Scholarships bear his name. His manuscripts are preserved in the Bibliothèque nationale de France.

Conclusion

Jules Supervielle stands as a singular example of the 20th Century French Poet. He forged a path between tradition and innovation. As a French poet, he embraced nature, memory, and the dream. He wrote with simple clauses and clear images. He never lost his sense of wonder. In comparison with Apol and others, he occupies a middle ground—modern yet classical, personal yet universal. His work enriches the tapestry of French poetry. It reminds us that, even in an age of complexity and conflict, a few words can open the heart to the vastness of the cosmos.