The 18th century in France was an era of Enlightenment, revolution, and a dynamic shift in intellectual thought. French poets of this period stood at a unique intersection between classical tradition and modern innovation. Among them, Antoine-Léonard Thomas played a distinct role. He was not only a French poet but also a moralist and academic who sought to unite poetic elegance with philosophical depth. Though not as widely known today as Voltaire or Rousseau, Thomas carved a niche for himself in French poetry through his meditative odes, eloquent prose, and philosophical reflections.

This article examines the life, works, and legacy of Antoine-Léonard Thomas. It places him within the context of 18th century French poetry and compares him with other literary figures of his time. The analysis will show how Thomas’s work reflects the era’s cultural concerns and moral debates, and why he deserves renewed attention today.

Antoine-Léonard Thomas

Antoine-Léonard Thomas was born on October 1, 1732, in Clermont-Ferrand, France. He came from a modest background but demonstrated a precocious talent for literature. He was educated by Jesuits, a common path for intellectuals of his era. The Jesuit emphasis on rhetoric and classical literature deeply influenced his early development.

From a young age, Thomas showed an aptitude for writing and oratory. He excelled in Latin and Greek, which later informed his stylistic choices and thematic preferences. Like many 18th century French poets, Thomas absorbed the models of antiquity, particularly Horace and Cicero, blending their moral seriousness with the clarity and reason favored by Enlightenment thinkers.

Professional Rise and Academic Career

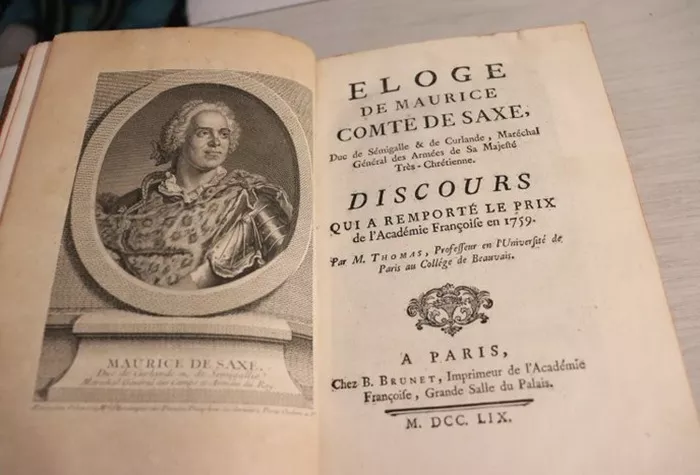

Antoine-Léonard Thomas gained recognition in 1760 when he won a prize from the Académie française for his essay Éloge de Marc-Aurèle (Eulogy of Marcus Aurelius). This work exemplified the blend of stoicism, reason, and civic virtue that marked his poetic and philosophical sensibility.

Thomas became a prominent member of the Académie française, ultimately serving as its permanent secretary. His acceptance into such an elite institution highlighted his intellectual prestige. Unlike more flamboyant contemporaries like Voltaire, Thomas was reserved and scholarly. Yet, his influence within academic circles was significant, particularly in shaping the style and content of public discourse.

Thematic Concerns in Thomas’s Poetry

Thomas’s work can be described as moralistic and meditative. His odes often explore themes such as virtue, justice, death, and public duty. As a French poet, he sought to align poetic beauty with ethical purpose. This dual concern sets him apart from the more hedonistic or satirical voices of the time.

For instance, his Ode sur la mort de Jean-Jacques Rousseau mourns the passing of the great philosopher while reflecting on the tension between genius and society. In this ode, Thomas shows his deep admiration for Rousseau’s commitment to virtue and truth, while subtly lamenting the loneliness of intellectual honesty in a corrupt world.

His poetry typically avoids personal confession or romantic subjectivity. Instead, it engages with collective values and public morality. This characteristic links him more to the classical tradition than to the burgeoning Romanticism of the later 18th century.

Style and Structure in Thomas’s Work

Thomas favored elevated language, clear syntax, and classical forms. His verses are composed with careful attention to rhythm and balance. The influence of ancient rhetoric is evident in his structured arguments and persuasive tone.

While not known for musicality or sensual imagery, Thomas’s poetry is marked by intellectual rigor. He often used enjambment and antithesis to highlight moral contrasts. His odes are didactic but not dry, shaped by a belief that poetry should uplift and instruct.

In this way, Thomas differs from poets such as André Chénier, whose work would later move toward a more lyrical and emotional style. Chénier, who was executed during the French Revolution, embodied the transition toward Romanticism. Thomas, by contrast, represents the final flowering of the classical tradition in 18th century French poetry.

A Comparative View: Thomas and Voltaire

It is inevitable to compare Antoine-Léonard Thomas with Voltaire, one of the most prominent figures of 18th century French literature. Both were French poets and intellectuals who contributed to Enlightenment thought. Yet their temperaments and literary goals diverged sharply.

Voltaire was a satirist and a polemicist. He used wit to challenge dogma and ridicule hypocrisy. His poetry often served political and philosophical ends. In contrast, Thomas was more measured. He used poetry as a means to reflect on eternal truths and human dignity.

While Voltaire’s verse could be biting and playful, Thomas’s was solemn and idealistic. Both sought to educate their readers, but their methods and moods differed. Voltaire appealed to the reader’s sense of irony and skepticism; Thomas appealed to reason and moral seriousness.

Thomas and the French Revolution

Antoine-Léonard Thomas died in 1785, just a few years before the outbreak of the French Revolution. His passing spared him from witnessing the violence and upheaval that shook France to its core. However, his writings show a keen awareness of the social tensions of his time.

His eulogies for great men—Marcus Aurelius, Descartes, and Rousseau—read as calls for civic virtue and ethical leadership. These values would later be echoed in revolutionary discourse. In this sense, Thomas was a precursor to revolutionary idealism, though not a revolutionary himself.

Had he lived longer, it is unclear whether Thomas would have supported or opposed the Revolution. Given his conservative moralism and preference for order, he might have viewed the violence with alarm. Yet his commitment to reason and virtue aligns him with some of the Revolution’s initial goals.

Legacy and Influence

Thomas was admired during his lifetime and well into the 19th century. His essays and odes were republished multiple times, and his reputation as a moralist endured. However, changing tastes in poetry eventually led to his decline in popularity.

Romanticism, with its emphasis on emotion, nature, and individuality, overshadowed the moral classicism of Thomas. Poets like Lamartine and Hugo, who embraced subjectivity and visionary imagery, found little inspiration in Thomas’s structured moralism.

Yet in recent decades, scholars have returned to figures like Thomas to understand the full complexity of 18th century French poetry. His work offers insight into the intellectual debates of his time, especially the role of virtue, reason, and public duty in literature.

Reappraising Antoine-Léonard Thomas Today

In contemporary literary studies, there is growing interest in reevaluating overlooked poets of the Enlightenment. Antoine-Léonard Thomas is one such figure. His writing serves as a bridge between classical tradition and Enlightenment humanism.

His works are valuable for understanding how French poets responded to the philosophical shifts of their time. Thomas was not a poet of revolution or romantic rebellion, but of thoughtful moderation. In an age often polarized between progress and reaction, his voice represents the Enlightenment’s call for reasoned reform.

Moreover, in our own era of political and ethical confusion, Thomas’s focus on virtue and civic responsibility seems newly relevant. His belief that poetry can shape moral character is a message worth revisiting.

Selected Works and Critical Reception

Among his major poetic and prose works are:

Éloge de Marc-Aurèle (1760)

Éloge de Descartes (1765)

Éloge de Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1772)

Odes et poésies (a collected volume)

These texts combine biography, moral reflection, and poetic structure. His Éloges are especially significant. More than praise, they are meditations on what it means to live a virtuous life. These pieces contributed to a genre unique to 18th century French literature: the philosophical eulogy.

Critics in the 19th and early 20th centuries sometimes dismissed Thomas as dry or overly rhetorical. But more recent interpretations appreciate his stylistic clarity and ethical passion. Scholars now see him not just as a moralist, but as a craftsman of ideas, a poet who gave intellectual form to Enlightenment ideals.

Conclusion

Antoine-Léonard Thomas may not be the most famous French poet of the 18th century, but his work embodies the spirit of the Enlightenment in a unique and dignified way. His poetry is not dazzling, but it is thoughtful. It does not seduce with emotion, but it instructs with conviction.

As we continue to explore the range of voices in 18th century French poetry, Thomas deserves a place in the conversation. He represents the intellectual conscience of his time—a voice of reason, restraint, and moral purpose.

In comparing him with other poets of the era—from Voltaire’s sharp satire to Chénier’s lyrical innovation—we see how diverse and rich this period was. Antoine-Léonard Thomas reminds us that poetry is not only for beauty or rebellion but also for wisdom.

His life and works stand as a testament to the power of poetry to reflect and shape the moral imagination. In a world still wrestling with the balance between reason and passion, Thomas’s voice is one worth hearing anew.