Eugen Gomringer stands as a defining figure in 20th-century German poetry, particularly as the father of concrete poetry, a form that fundamentally reshaped the relationship between language and visual space. Unlike traditional lyricism or narrative-driven verse, Gomringer introduced a poetics that emphasizes visual arrangement, simplicity, and immediacy. Born in 1925 in Bolivia to a Swiss father and a German mother, Gomringer’s multi-cultural roots and multilingual fluency enabled him to reimagine poetry as an international medium — one that transcends national boundaries and linguistic barriers.

The 20th century saw German poets grappling with the legacy of war, trauma, and modernity. While many poets turned inward to explore personal and collective memory, Gomringer offered a radical alternative. He envisioned poetry not as a vehicle for confession or political commentary but as a constructed object — a linguistic constellation that could be seen and experienced as much as it could be read. His innovation marked a clean break from the emotionally heavy, historically burdened traditions of German literature.

This article delves into Gomringer’s life, philosophy, and achievements. It explores the intellectual backdrop of his work, the aesthetic of concrete poetry, his international collaborations, and his position alongside contemporaries such as Paul Celan, Ingeborg Bachmann, and Hans Magnus Enzensberger. Through a comparative and contextual lens, we will see how Eugen Gomringer reshaped the poetic landscape of the 20th century.

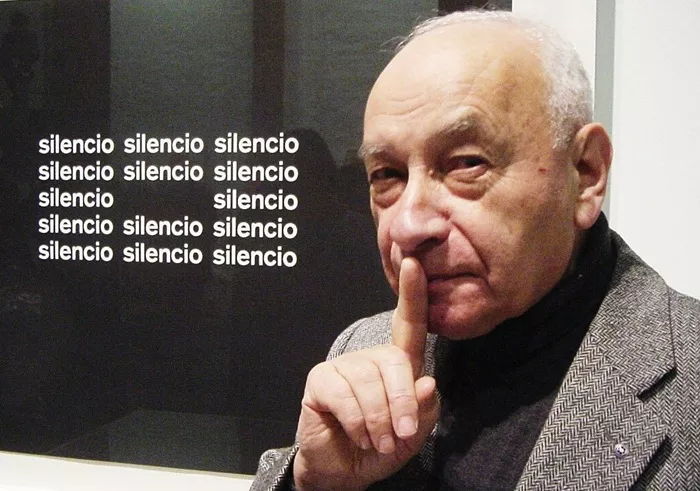

Eugen Gomringer

Eugen Gomringer was born on January 20, 1925, in Cachuela Esperanza, a small Bolivian town near the Brazilian border. Raised in a multicultural household, Gomringer spoke Spanish, German, and French, a formative influence that nurtured his interest in the mechanics of language. His father, a Swiss engineer, and his German mother ensured that education and discipline played central roles in his upbringing.

In the late 1940s, Gomringer moved to Switzerland and enrolled at the University of Bern, where he studied economics and art history. The precision of economics and the aesthetics of modern art shaped his emerging literary philosophy. It was during this time that he became increasingly influenced by the Bauhaus school and Swiss design aesthetics, especially the work of Max Bill, who later collaborated with him. He was particularly drawn to Constructivism, with its emphasis on function, clarity, and geometric order.

Rather than engaging with the emotionally dense poetics emerging in post-war Germany, Gomringer focused on structure, space, and the visual potential of language. His approach to poetry was shaped not only by literary traditions but also by architectural and typographic disciplines. For Gomringer, the poem was not a lament or confession — it was a designed object, precise and intentional.

The Concept and Characteristics of Concrete Poetry

Concrete poetry redefines the boundaries between literature and visual art. It is not merely about what the words mean, but how they appear. Eugen Gomringer’s role in formulating and formalizing concrete poetry cannot be overstated. He saw the poem as a visual composition, where linguistic elements interacted on the page to produce meaning through form, repetition, and spatial orientation.

His 1954 manifesto, vom vers zur konstellation (“from line to constellation”), laid out the theoretical foundations of the movement. In it, Gomringer argued that poetry should be economical, universally accessible, and stripped of unnecessary ornament. The idea of a “constellation” represented a poetic structure that was not linear but spatial — a fixed field of elements that readers could absorb holistically.

One of his most iconic works, “avenidas,” captures this philosophy:

avenidas

avenidas y flores

flores

flores y mujeres

avenidas

avenidas y mujeres

avenidas y flores y mujeres y

un admirador

This poem, composed in Spanish, illustrates his belief in repetition and rhythm as tools of both visual and linguistic power. The simplicity of vocabulary belies a deeper rhythm, an architectural harmony. The reader does not follow a story — they enter a space.

Concrete poetry challenged traditional poetics by divorcing language from its usual syntactical flow. Gomringer’s poems are often unpunctuated, without verbs or narrative cues. They do not describe reality — they construct one.

Gomringer’s Role in 20th Century German Poetry

In a century of profound literary upheaval, Gomringer’s work marked a distinctive turn toward formal innovation. Post-war German poetry was dominated by existential inquiry and philosophical introspection. Poets like Paul Celan grappled with Holocaust trauma, and Günter Eich confronted the ethical dimensions of war and memory. Amid this somber landscape, Gomringer’s clarity and abstraction were revolutionary.

His refusal to use poetry as a vehicle for political or emotional testimony positioned him outside the dominant currents of his time. Yet this was precisely his strength. By shifting attention to the materiality of language, Gomringer redefined poetic value. He aligned his work with international modernism — artists like Piet Mondrian, Wassily Kandinsky, and Le Corbusier — rather than with literary traditionalists.

Furthermore, Gomringer’s theoretical contributions positioned him as a guiding figure for an entire generation of poets and designers. His essays explored the poet not as a bard or prophet but as a language engineer, someone who crafts experiences with minimalist precision. He encouraged others to think of poetry as a medium, not just a message.

His work at institutions like the Hochschule für Gestaltung in Ulm allowed him to teach this philosophy across disciplines. Students of typography, graphic design, and architecture all found relevance in his ideas, and his poetic reach extended well beyond Germany.

The International Impact of Eugen Gomringer

Eugen Gomringer’s influence was global in scope. His multilingual capabilities allowed him to write in German, Spanish, French, and English, enabling broad dissemination of his work. In the 1950s, he connected with the Brazilian Noigandres group — a pioneering collective of poets who were independently developing concrete poetry in South America.

This collaboration helped form a transatlantic network of concrete poets. Together with Augusto de Campos, Haroldo de Campos, and Décio Pignatari, Gomringer co-authored manifestos and exhibitions that defined the international style of concrete poetry. These poets shared a belief in the universality of visual language and the democratization of literary forms.

Gomringer’s role as a cultural diplomat was enhanced by his leadership at the Institut für Konstruktive Kunst und Konkrete Poesie (IKKP) and the Swiss Concrete Foundation. His works were featured in major art exhibitions, often alongside paintings and installations, further blurring the line between poetry and visual art.

He lectured extensively in Europe, Latin America, and Asia, helping to plant the seeds of concrete poetry in multiple cultural contexts. In doing so, he ensured that this new poetic form would not remain a German experiment but would become a global phenomenon.

Comparison with Contemporary Poets

To better understand Eugen Gomringer’s singularity, we can contrast his work with that of his contemporaries:

Paul Celan dealt with the trauma of the Holocaust, creating poetry that was dense, elliptical, and deeply symbolic. Celan’s work is often cryptic, layered with references to loss and survival. Gomringer, in contrast, stripped language of historical weight, aiming instead for neutrality and clarity.

Ingeborg Bachmann focused on the politics of identity, love, and alienation. Her rich, lyrical style stands in stark contrast to Gomringer’s austere constructions. Where Bachmann sought emotional resonance, Gomringer sought aesthetic function.

Hans Magnus Enzensberger infused his poetry with political critique and irony. He was a public intellectual, engaging directly with contemporary social issues. Gomringer rejected polemics, positioning his poems outside the immediate currents of history.

These comparisons highlight Gomringer’s radical departure from mainstream German poetry. His emphasis on form over content, visual over symbolic, universal over national, placed him in a unique category — not against his contemporaries, but beside them, charting a different course.

Themes and Philosophy in Gomringer’s Poetry

At the heart of Gomringer’s philosophy is the idea that language is material. Just as a sculptor works with clay or a designer with shapes, Gomringer works with words — not as vehicles of narrative but as objects with inherent spatial and aesthetic value.

His themes are deliberately neutral: avenues, flowers, admiration, objects, environments. These are chosen not for their emotional charge but for their capacity to be arranged into visual systems. In this sense, Gomringer’s poetry is post-literary — it aspires to the condition of architecture or painting.

Another central concept is participation. The poem is not a completed thought but an invitation to the reader to interact, to make meaning through experience. Gomringer’s poems are never prescriptive; they are spaces to be explored.

His commitment to accessibility is also key. Gomringer believed that poetry should not belong to an elite but should be approachable to anyone. His minimalist style opens the door to non-specialists, allowing his work to be exhibited in public spaces, taught in schools, and adapted for digital formats.

Legacy and Continuing Influence

Today, Eugen Gomringer’s legacy continues to thrive. His daughter, Nora Gomringer, is a celebrated poet in her own right, known for performance poetry and spoken word, and she helps manage the Gomringer archrequently cited in discussions of intermedia art, typographic design, and visual culture. Digital poets and artists working with code, animation, or augmented reality often cite Gomringer as an inspiration, noting that his spatial logic anticipated many aspects of digital expression.

Museums and galleries continue to exhibit his poetry, often presenting it not in books but on walls, floors, or screens — fitting for a poet who always saw words as visual elements. Academic programs across Europe and Latin America include Gomringer in courses on modernist literature, design theory, and poetics.

In 2011, his poem “avenidas” was installed on the wall of a university building in Berlin, sparking debate over public art, poetry, and feminism — a testament to his continued relevance in cultural discourse.

Conclusion

Eugen Gomringer holds a singular position in the history of 20th-century German poetry. While his contemporaries used verse to grapple with memory, trauma, and politics, Gomringer chose clarity, structure, and universality. His concrete poetry transformed the way we think about language — not as a flow of syntax and metaphor, but as form, rhythm, and space.

As both a poet and theorist, Gomringer helped shape modern poetry not only in Germany but globally. His minimalist yet radical approach invited audiences to see and experience poetry in new ways. Through spatial arrangement, linguistic economy, and visual experimentation, Gomringer made poetry more democratic and more profound.

His legacy lives on in visual poetry, graphic design, digital media, and contemporary literature. He is not merely a poet of his time — he is a poet for our time, and for the future.