Hans Sahl (1902–1993) occupies a significant position in the landscape of 20th Century German poetry. As a German poet, literary critic, novelist, and translator, Sahl’s life was profoundly shaped by the political turmoil of his time. His writings, produced largely in exile, give voice to the displaced, the persecuted, and the intellectually exiled of his era. Through his poetry, Sahl confronted themes of alienation, human dignity, and resilience. He is emblematic of a generation of German poets whose identities and art were inseparable from the traumas of the century in which they lived.

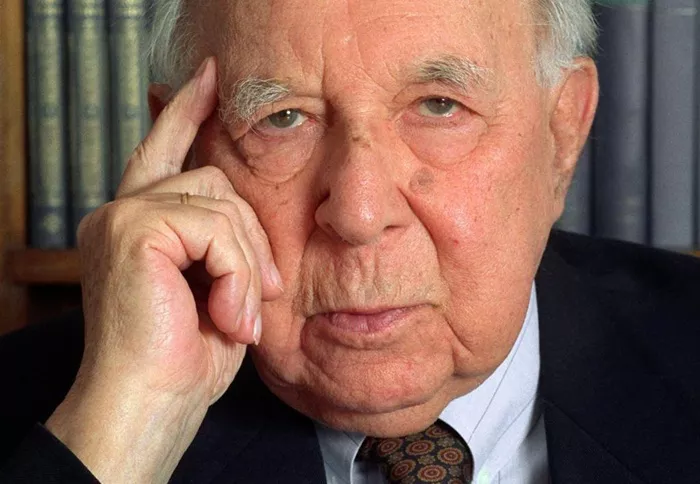

Hans Sahl

Hans Sahl was born Hans Salomon in Dresden in 1902 into an assimilated Jewish family. His early education reflected the cultural richness of pre-war Germany. He studied art history and literature in cities like Leipzig, Munich, and Berlin, eventually completing his doctoral studies. As a young intellectual, Sahl became embedded in Berlin’s thriving cultural and political scene during the Weimar Republic. He wrote theater and film criticism and began to establish himself as a literary figure.

The Nazi Rise to Power and the Life of an Exile

With the rise of the Nazi regime in 1933, Sahl—both Jewish and politically aligned with anti-fascist ideals—was forced into exile. This would become the defining experience of his life. Like many other 20th Century German poets, his career was abruptly interrupted by persecution and displacement.

He fled first to Prague, then to Switzerland, and eventually to France. There, he was interned as a “foreign enemy” but managed to escape. He worked with other exiled intellectuals to help refugees escape from Nazi-occupied Europe. His path eventually led him to the United States, where he spent nearly two decades.

Sahl’s exile deeply shaped his literary themes. He saw himself not just as an individual fleeing persecution, but as a representative of a broader cultural dislocation. The German poet in exile became a figure of resistance, remembrance, and cultural continuity.

Literary Themes and Style

Sahl’s poetry is marked by restraint, clarity, and a moral urgency. His style is classical in structure, yet modern in tone. He is known for crafting direct, deceptively simple lines that carry the weight of moral witness. The trauma of exile, the experience of rootlessness, and the anguish of cultural and personal dislocation recur as major themes.

In one of his most famous poems, Der Maulwurf (“The Mole”), Sahl uses the metaphor of the mole—blind, burrowing, persistent—to capture the inner life of the refugee. The mole does not live in light but in darkness, moving forward with instinct and memory. This became a signature metaphor for the 20th Century German poet in exile.

Unlike other exilic writers who turned to overt lament or mysticism, Sahl maintained a tone of sober reflection. His verses offered little in the way of romantic idealism. Instead, they embodied the paradox of the exiled intellectual: alienated from their homeland but unable to sever the cultural and linguistic ties to it.

Contribution to German Literature and Translation

While in the United States, Hans Sahl became an important cultural mediator. He worked as a journalist and literary critic but made his greatest impact through translation. Sahl introduced many American playwrights to German audiences by translating works of Arthur Miller, Tennessee Williams, and Thornton Wilder into German.

Through these translations, Sahl helped reshape postwar German literary culture. He brought new voices, styles, and themes into the German literary imagination, thereby reconnecting German readers with the global literary scene from which they had been isolated during the Nazi years.

Sahl’s commitment to the German language, even while in exile, underscores his identity as a German poet. His works, though written abroad, belong firmly to the tradition of German poetry. His exile was geographical, not cultural or linguistic.

Return to Germany and Recognition

Hans Sahl returned to Germany in the 1980s after more than four decades in exile. His reception was cautious at first; postwar Germany was slow to acknowledge the voices of its exiled artists. However, over time, Sahl received numerous awards and honors.

These included membership in the German Academy for Language and Literature, the Goethe Medal, and several prestigious literary prizes. In the final decade of his life, Germany formally acknowledged his role as a vital figure in 20th Century German poetry. His works were republished, and his contributions as both poet and translator were celebrated.

The late honors reflect a broader pattern in German literary history: the posthumous rehabilitation of exiled writers who had been ignored or marginalized during their lifetimes. Sahl’s recognition came as part of Germany’s effort to confront its cultural and historical amnesia.

Comparison with Other 20th Century German Poets

Sahl’s position in German poetry is often considered alongside fellow exiles like Nelly Sachs, Stefan Zweig, and Paul Celan.

Nelly Sachs, also Jewish and exiled, won the Nobel Prize for her haunting, mystical poetry about the Holocaust and Jewish suffering. Her work is spiritual and symbolic, while Sahl’s is rational and grounded in concrete experience.

Paul Celan, a post-war German-language poet, grappled with the Holocaust through dense, image-laden poetry. Celan’s language is fragmented, nearly opaque—a stark contrast to Sahl’s lucidity. Where Celan delved into silence and trauma, Sahl maintained a moral clarity.

Stefan Zweig, although primarily known as a novelist and essayist, shared with Sahl the fate of exile and cultural displacement. Both wrote with nostalgia for a lost Europe, though Sahl retained a more overtly political voice.

Compared with these contemporaries, Sahl occupies a middle ground. He avoided abstraction but did not descend into propaganda. He was philosophical without being obscure. Among 20th Century German poets, Sahl stands out for his balance of ethical urgency and literary craft.

The Role of the German Poet in Exile

Hans Sahl’s career exemplifies the particular role of the German poet in exile. The exilic condition in the 20th century was not merely physical but linguistic and cultural. For poets like Sahl, the German language was both homeland and exile. Writing in German while being politically and physically alienated from Germany became a form of protest and preservation.

Sahl believed that the German poet had a duty to bear witness, to preserve cultural memory, and to challenge the distortions of history. This belief informed both his poetry and his translations. He was not only recording the exile experience but also resisting cultural erasure.

The Hans Sahl Legacy

Hans Sahl died in 1993 in Tübingen. His legacy remains alive through his poetry, translations, and essays. More importantly, his life and work are studied as part of the broader canon of German exile literature.

A literary prize bearing his name, the Hans-Sahl-Preis, honors writers who share his liberal, anti-totalitarian values. It reflects the lasting importance of his commitment to intellectual freedom and literary integrity.

As a 20th Century German poet, Sahl contributed not just through his writing but through the values he upheld. His work affirms the power of poetry to survive displacement, and the power of language to maintain continuity in the face of historical rupture.

Conclusion

Hans Sahl is a vital figure in the history of 20th Century German poetry. His life and work illuminate the challenges faced by the German poet in exile—challenges of language, identity, and historical responsibility. Through his poetry and translations, Sahl preserved a vision of ethical clarity and cultural continuity.

Unlike some of his contemporaries who sought to break with the past, Sahl remained anchored in the German literary tradition, even as he was cast out of the country of his birth. His poetry is a testament to the resilience of the human spirit and the enduring power of literature to give voice to the exiled, the displaced, and the forgotten.

Hans Sahl’s legacy invites us to rethink what it means to be a German poet in the 20th century: not merely one who writes in German, but one who carries the burden of memory, exile, and moral witness into every stanza.