Rolf Dieter Brinkmann is one of the most important and controversial figures in 20th century German poetry. Born in 1940 and tragically killed in 1975, his life was short, but his influence remains profound. Brinkmann pushed the boundaries of form, language, and content. His writing broke with post-war traditions and introduced a raw, experimental, and deeply personal voice to German poetry. Through this article, we will explore his biography, themes, styles, and legacy. We will also compare him with other 20th century German poets to place his work in a broader literary context.

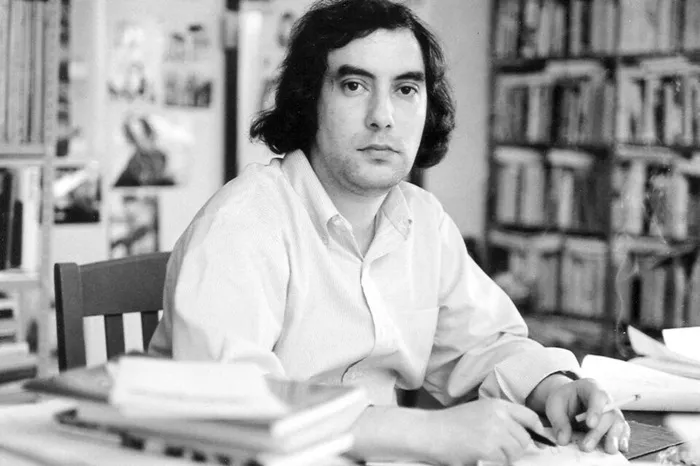

Rolf Dieter Brinkmann

Rolf Dieter Brinkmann was born on April 16, 1940, in Vechta, a small town in Lower Saxony, Germany. He was raised in a conservative environment shaped by the trauma and destruction of World War II. Like many 20th century German poets, Brinkmann experienced the tensions between the memory of war and the new, modern realities of postwar West Germany.

He began writing poetry in his teenage years. His early works show the influence of traditional German poetry. However, his interest quickly turned to modernist and avant-garde literature, especially from the United States and France. American poets such as William Carlos Williams, Frank O’Hara, and Ezra Pound deeply inspired him. These poets offered new ways of seeing the world and expressing personal experiences.

Brinkmann studied German literature and art history in Cologne. His academic background gave him access to the classics, but he never fully accepted the conventional literary culture of the university. He wanted to create a new kind of poetry—one that reflected the chaos and vitality of modern life.

The Cologne Years and Early Publications

In the 1960s, Brinkmann settled in Cologne, where he became part of a vibrant artistic and literary scene. His first major work, Keiner weiß mehr (1968), challenged the conventions of German poetry. This collection combined everyday language with surreal images and sudden emotional shifts. The poems were marked by a sense of alienation and anger, but also by a desire to connect with the world in new ways.

Brinkmann’s writing from this period often reflects a struggle between private experience and public life. He was influenced by pop culture, film, radio, and advertising. He experimented with montage and collage techniques, sometimes mixing prose, poetry, and visual art in a single work. This was a significant departure from the more traditional lyricism that still dominated much of 20th century German poetry.

Key Themes in Brinkmann’s Work

1. Urban Life and Alienation

Brinkmann’s poetry often depicts city life in its most chaotic and fragmented forms. He wrote about neon lights, crowded streets, and late-night radio programs. The city was not a place of peace or beauty, but a space of confusion and sensory overload. In this way, he captured the alienation of the individual in modern society.

2. The Body and Desire

Many of his poems focus on the physical body. He wrote about sex, desire, pain, and illness with shocking honesty. This emphasis on the body was rare in postwar German poetry, which often remained abstract or politically focused. Brinkmann’s focus on the body connected him with international literary movements like the Beat Generation.

3. Time and Transience

Brinkmann was haunted by the passage of time. His poems often reflect a sense of impermanence. He used fleeting images—sunlight on a window, a passing face, a voice on the radio—to suggest that life is always slipping away. This melancholy tone contrasts with the energy and aggression found in other parts of his work.

4. Rebellion Against Tradition

Above all, Brinkmann was a rebel. He wanted to destroy the stale forms of German poetry and replace them with something urgent and alive. He attacked established writers and institutions. His essays and interviews were filled with polemic statements. He wanted poetry to be direct, dangerous, and honest.

Brinkmann and the American Influence

One of the key aspects that set Brinkmann apart from other 20th century German poets was his strong connection to American literature. While many of his contemporaries looked to the German or European tradition, Brinkmann was reading the New York School poets and Beat writers.

In 1972–73, Brinkmann spent a year in Austin, Texas, as a visiting fellow. During this time, he wrote and translated extensively. He absorbed the rhythms and aesthetics of American life and brought them into his German writing. The result was Rom, Blicke (1979, posthumously published), a collage of poems, photographs, diary entries, and reflections. It remains one of the most innovative books in German literature.

His engagement with American poets helped modernize German poetry. It also reflected a shift in postwar cultural identity. Instead of looking to the German past, Brinkmann looked outward—to America, to modernity, to everyday life.

Comparison With Other 20th Century German Poets

To better understand Brinkmann’s unique role, it is useful to compare him with other major figures in 20th century German poetry.

Paul Celan

Paul Celan (1920–1970) is often considered the most important German poet after World War II. His work deals with trauma, memory, and the Holocaust. Celan’s language is dense, symbolic, and philosophical. In contrast, Brinkmann’s poetry is fast, raw, and emotional. While Celan looks inward into language and loss, Brinkmann looks outward into the chaos of contemporary life.

Ingeborg Bachmann

Ingeborg Bachmann (1926–1973) also explored themes of war, gender, and identity. Her poetry is elegant and introspective. Bachmann used lyric forms to investigate existential and political questions. Brinkmann admired her work but rejected her style. He wanted to destroy lyrical beauty and replace it with a kind of poetic realism.

Hans Magnus Enzensberger

Enzensberger (b. 1929) is a major intellectual and poet. He used satire and irony to critique modern society. He often wrote about politics, media, and technology. Brinkmann shared Enzensberger’s critical eye but rejected his detached tone. Brinkmann’s poetry is more visceral and emotional.

Peter Handke

Peter Handke (b. 1942) emerged around the same time as Brinkmann. Both challenged literary norms and experimented with language. However, Handke focused more on narrative and theater, while Brinkmann remained devoted to poetic form. Handke’s tone is often cool and philosophical, while Brinkmann’s is urgent and personal.

Brinkmann’s Use of Form and Language

Brinkmann was not only a poet of content but also of form. He experimented with how poems looked and sounded. He used long lines, sudden breaks, and unexpected punctuation. Sometimes his poems read like diary entries or letters. Other times they explode with strange images and disjointed thoughts.

He also used collage and montage. He would take snippets from newspapers, advertisements, conversations, and music lyrics. These fragments created a layered and chaotic poetic space. This technique echoed the visual art of the 1960s and 70s, such as Pop Art and Dada.

Brinkmann’s language was direct and unfiltered. He avoided traditional metaphors or elevated diction. Instead, he used the speech of everyday life—filled with slang, anger, and humor. This made his poetry feel alive and relevant.

Death and Posthumous Recognition

In April 1975, shortly after attending a literary conference in London, Rolf Dieter Brinkmann was struck by a car and killed. He was only 35 years old. His death shocked the literary world. At the time, he was working on several new projects, and many believed he was just entering his creative prime.

After his death, his wife Maleen Brinkmann helped edit and publish much of his remaining work. Collections like Rom, Blicke and Westwärts 1 & 2 (1975) cemented his reputation. These books showed the full range of his talent and vision.

Today, Brinkmann is recognized as a central figure in 20th century German poetry. He is studied in universities and included in anthologies. His work continues to influence young poets and artists.

Legacy and Influence

Rolf Dieter Brinkmann’s legacy is multifaceted. He changed the way German poetry could sound, look, and feel. His emphasis on personal experience, his experimental style, and his global influences opened new paths for writers in Germany.

Many contemporary German poets, such as Thomas Kling, Durs Grünbein, and Marcel Beyer, acknowledge Brinkmann as a major influence. His mix of raw emotion and formal innovation remains relevant in today’s poetry scene.

Brinkmann also helped introduce a transatlantic dialogue in literature. He showed that German poetry could learn from and contribute to global movements. His translations and adaptations of American poets helped expand the literary horizon of postwar Germany.

Brinkmann in Today’s Cultural Landscape

In recent years, there has been renewed interest in Brinkmann’s work. New editions, biographies, and critical studies have appeared. His notebooks, audio recordings, and visual art have been exhibited. Digital archives have made his work more accessible.

Young readers are drawn to his honesty and energy. In an age of social media and fragmented attention, Brinkmann’s quick, collage-like style feels surprisingly modern. His poetry captures the speed and strangeness of life in a way that still resonates.

Conclusion

Rolf Dieter Brinkmann remains one of the most original and influential voices in 20th century German poetry. He challenged the norms of his time and created a body of work that is still studied, debated, and admired. His poetry reflects a deep engagement with the self, the city, and the modern world. Through his experimental forms and personal themes, he opened new possibilities for German poets.

His life was brief, but his work endures. In the history of German pllious innovator—a poet who gave voice to the confusion, anger, and beauty of modern life. His legacy is not only literary but cultural. He helped redefine what it means to be a German poet in the late 20th century.

Whether through his raw language, his formal daring, or his fierce independence, Rolf Dieter Brinkmann continues to inspire. He remains a powerful reminder that poetry can be a force of disruption, connection, and truth.