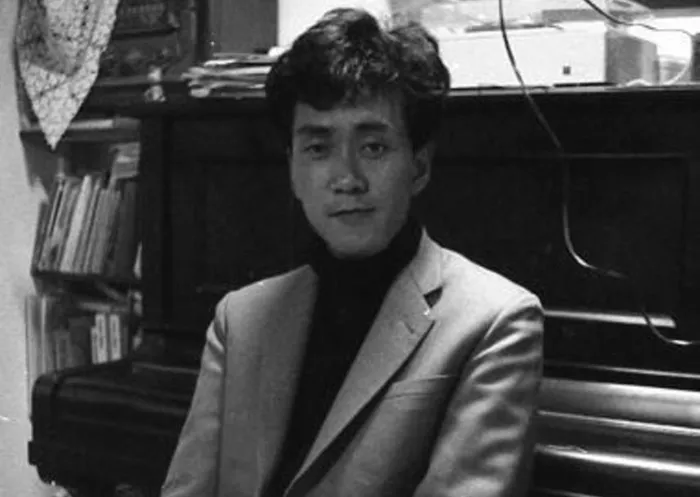

Among the varied voices that shape the world of 21st century Japanese poets, the work of Teizo Matsumura holds a distinct and haunting resonance. Though born in 1929 and best known internationally as a composer, Matsumura’s literary contributions reflect a deeply poetic mind shaped by war, illness, and spiritual searching. As a Japanese poet, Matsumura’s legacy may not be as widely recognized as that of his contemporaries in literary circles, but his written words and their connection to his musical works present a unique fusion of art forms. His poetry reflects themes of impermanence, beauty, and existential solitude—hallmarks of traditional Japanese poetry, yet rendered in a modern, minimalist voice suited for the 21st century.

The Historical Context and Emergence of a Poetic Voice

Teizo Matsumura came of age during one of the most tumultuous periods in modern Japanese history. Having survived tuberculosis and the destruction of war, he was intimately familiar with the fragility of life. These early experiences shaped not only his compositions but also the sparse, refined language of his poetry. He did not publish widely as a poet in the traditional sense, yet many of his texts and song lyrics carry poetic depth, and they are often categorized by scholars as part of modern Japanese poetry. His works resonate with a subdued emotional tone, often resembling the aesthetics of waka and haiku but layered with the introspection of modern sensibility.

Unlike the exuberant experimentation seen in poets like Shuntarō Tanikawa or the politically charged narratives in the works of Gozo Yoshimasu, Matsumura’s approach to poetry is deeply inward. This introspective quality sets him apart among 21st century Japanese poets, many of whom engage actively with postmodernism, globalization, and digital culture. Matsumura remains a contemplative figure, rooted in tradition, yet forward-looking in his minimalism and emotional restraint.

Language, Silence, and the Poetic Imagination

Matsumura’s work is characterized by economy of language. Much like the music he composed—delicate, textured, and often quiet—his poetry avoids grand gestures. Instead, he captures emotions through suggestion rather than statement. This is consistent with traditional Japanese poetic forms, which often rely on seasonal references, subtle imagery, and the concept of yūgen—a mysterious grace.

This approach contrasts sharply with other 21st century Japanese poets such as Hiromi Itō, whose work is often visceral and embodied. While Itō’s poetry explores physicality, motherhood, and gender with boldness, Matsumura’s verses drift into the metaphysical. He rarely addresses the body directly; instead, his focus is on memory, sensation, and the space between sounds and words.

Matsumura’s use of silence is particularly notable. Many of his texts—especially those set to music—utilize pauses and empty space to create meaning. Silence becomes a kind of speech. In this way, he aligns with both Japanese Zen aesthetics and modernist poetics. His poetry is not built for performance or spectacle but for quiet reflection.

Themes and Motifs in Matsumura’s Poetic Work

The dominant themes in Matsumura’s writing include nature, death, time, and the search for spiritual peace. These are classic themes in Japanese poetry, from the ancient Manyōshū anthology to modern-day free verse. What makes Matsumura’s treatment of these subjects unique is his merging of Buddhist thought with post-war existentialism.

For instance, his meditative lyricism often explores the passage of time not as loss, but as transformation. In a short lyric about autumn, he writes not about the decay of leaves but about their drift into earth as an act of return. This perspective echoes the Buddhist idea of impermanence (mujo), a cornerstone of Japanese poetry. Yet Matsumura reframes this traditional view in the context of 20th-century trauma, suggesting not resignation but a deeper appreciation for fleeting beauty.

While other 21st century Japanese poets like Ryoichi Wago have responded directly to events such as the 2011 Fukushima disaster, often with political or urgent tones, Matsumura’s work is more timeless. His poetry does not anchor itself in contemporary events but instead in archetypal human experience. His voice remains relevant in the 21st century not because it engages current trends, but because it transcends them.

Intersections of Poetry and Music

Perhaps the most striking element of Matsumura’s poetic contribution is how it intersects with his musical compositions. He often set his own texts to music, blurring the line between poem and song. These works are not mere settings of verse, but fully integrated lyrical compositions. The words in his songs often read like minimalist poetry—distilled, suggestive, and full of subtle rhythms.

For example, his vocal work “Chinmoku no Kawa” (“The Silent River”) embodies both musical and poetic restraint. The text is sparse, evoking water, silence, and the passing of time. When paired with slow-moving harmonies and delicate instrumentation, the result is a work of emotional and spiritual depth. In such pieces, Matsumura acts not just as a composer or a Japanese poet, but as a bridge between artistic disciplines.

This synthesis of arts aligns with the broader trend in 21st century Japanese poetry, where many poets engage in interdisciplinary work. Poets like Kazuko Shiraishi have collaborated with jazz musicians; others have incorporated visual art or performance. Yet Matsumura’s integration of poetry and music feels organic and indivisible. He does not illustrate poetry with music; he embodies it.

The Legacy and Influence of Teizo Matsumura

Although Teizo Matsumura is more frequently discussed in the context of music history, his contributions to Japanese poetry should not be overlooked. His lyrical works and poetic texts continue to inspire both musicians and writers. They offer a model of how to create art that is both deeply personal and universally resonant.

Matsumura represents a unique position among 21st century Japanese poets. He is not part of the literary avant-garde nor the pop-culture-inflected streams of contemporary poetry. Instead, he stands as a solitary figure—quiet, meditative, and deeply sincere. His writing is grounded in the traditions of Japanese poetry, yet it speaks directly to modern sensibilities. His work shows that poetry does not need to shout to be heard.

In the age of digital media and fast consumption, Matsumura’s poetry reminds us of the value of stillness. His work invites readers to slow down, to listen, and to observe. As more scholars and artists revisit his texts, his poetic voice continues to echo, subtle but enduring.

Comparative Perspectives: Matsumura and His Contemporaries

To fully appreciate Teizo Matsumura’s place among 21st century Japanese poets, it is helpful to consider his contemporaries. As mentioned earlier, Shuntarō Tanikawa stands as a towering literary figure whose whimsical, philosophical, and at times playful poetry has captivated generations. Tanikawa’s poetic language is direct, his metaphors often surprising and fresh. His themes range from love and childhood to dreams and technology. In contrast, Matsumura’s voice is less playful and more austere. Where Tanikawa seeks wonder in the everyday, Matsumura seeks depth in silence.

Similarly, Gozo Yoshimasu is known for experimental, performative poetry that challenges the boundaries of language. His poems are often multilingual, visually complex, and performative in nature. Matsumura, by contrast, maintains a minimalist aesthetic that favors subtlety over innovation. Yet, the two share an interest in sound and rhythm, suggesting different paths within the same poetic landscape.

Another important figure is Nobuaki Fushimi, a poet and translator known for his Buddhist-influenced writing. Like Matsumura, Fushimi explores impermanence, emptiness, and spiritual insight. However, Fushimi’s poetry is more explicitly religious and textual, while Matsumura’s is more sensorial and musical.

These comparisons illustrate that Japanese poetry in the 21st century is not monolithic. It contains multiple voices, from the avant-garde to the traditional, from the politically engaged to the deeply personal. Teizo Matsumura’s contribution is unique because it synthesizes classical Japanese aesthetics with a post-war consciousness and musical sensibility. His place in the lineage of Japanese poets is secure not because of the volume of his work, but because of its purity and integrity.

Conclusion

Teizo Matsumura’s poetry, like his music, resists the noise of the modern world. It whispers where others shout. It pauses where others rush. As a Japanese poet, he offers a vision of art rooted in spiritual sensitivity and emotional restraint. His work exemplifies the power of suggestion over assertion, of listening over speaking.

In the broader tapestry of 21st century Japanese poets, Matsumura’s contribution may seem understated. Yet it is precisely this restraint that makes his voice essential. He reminds us that Japanese poetry, in all its forms—traditional and modern, spoken and sung—remains a vital source of meaning in a fragmented world.

As scholars and artists continue to explore the intersection of poetry and other disciplines, Teizo Matsumura’s legacy will likely grow. His poetic texts are already studied for their lyrical qualities, and his music remains widely performed. Future generations may come to see him not just as a composer with a poetic touch, but as a full-fledged poet of the 21st century—one whose work deserves to stand alongside the most celebrated voices in Japanese poetry.