Jean-Baptiste Rousseau remains one of the most intriguing figures in 18th Century French poetry. A poet of considerable linguistic talent and a master of sharp satire, Rousseau lived during a turbulent time in French literary and political history. He was known not only for his poetic accomplishments but also for his controversial involvement in public scandals that ultimately led to his exile. In contrast with his contemporaries such as Voltaire, Nicolas Boileau, and Jean-Baptiste Gresset, Rousseau’s work captures a unique fusion of wit, irony, and melancholy. His poems reflect both the grandeur and instability of the French Enlightenment.

This article explores the life, work, and legacy of Jean-Baptiste Rousseau as a French poet. It examines his place within 18th century French poetry, compares him to other poets of his time, and assesses how his exile shaped his contributions to literature. In doing so, it seeks to shed light on a complex literary figure often overshadowed by the Enlightenment’s more celebrated voices.

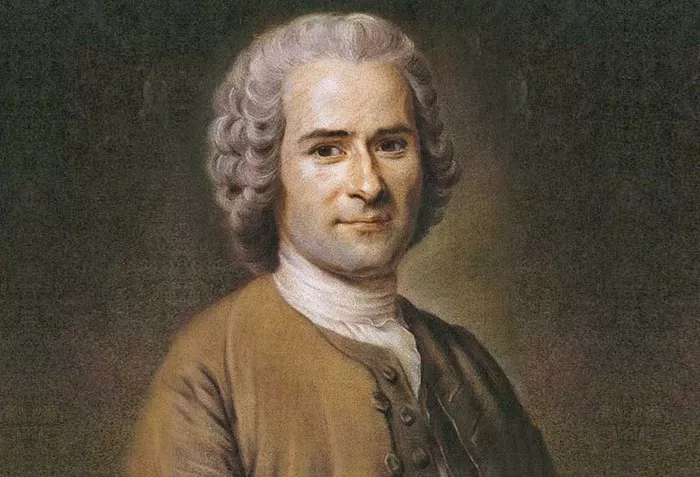

Jean-Baptiste Rousseau

Jean-Baptiste Rousseau was born in Paris on April 6, 1671, into a bourgeois family. His father was a shoemaker, and although Rousseau’s background was humble, he received a solid education at the Collège Louis-le-Grand. From an early age, he showed a keen interest in literature and language. He soon made his mark as a French poet through his lyrical and satirical verse.

Rousseau’s early poems were mainly odes and epigrams. These early works were elegant and refined, showing the influence of classical antiquity, especially Latin poets such as Horace and Juvenal. Like many French poets of the time, Rousseau believed that poetry should both instruct and delight. His talent was recognized by his contemporaries, and he quickly rose in literary circles.

Yet Rousseau was not content to follow the norms of polite verse. He was drawn to satire. This tendency would become both his trademark and his undoing.

The Power of Satire in Rousseau’s Work

In 18th century France, satire was a dangerous weapon. Poets who used their pen to mock others risked offending powerful figures. Jean-Baptiste Rousseau understood this risk, but he chose to pursue satire as a form of truth-telling.

Rousseau’s satirical epigrams targeted the hypocrisies of court life, the corruption of clergy, and the pretensions of the literati. His sharp wit earned him admirers but also enemies. His satires stood in contrast to the more balanced and polished works of Nicolas Boileau, another important 18th century French poet, who promoted clarity and classical restraint in poetry.

While Boileau sought harmony and rationality in verse, Rousseau embraced emotional sharpness and verbal attack. This divergence shows the range of styles in 18th century French poetry. Rousseau’s satires reflected a more rebellious and critical stance than Boileau’s didactic tone.

His most famous epigrams are short, pithy, and merciless. They cut to the core of his subjects. However, one such collection of biting verses led to serious legal troubles and eventually exile.

Exile and Infamy

In 1712, Rousseau was accused of writing a set of libelous poems that defamed influential people in Paris. Though he denied authorship, he was convicted and sentenced to permanent exile from France. This was a defining moment in his life and career. While some believed he was the victim of literary rivalry and political maneuvering, others thought he deserved punishment for his bold irreverence.

He fled first to Switzerland and later to Vienna and Brussels. Though in exile, Rousseau continued to write. His themes grew darker, more introspective, and more philosophical. His sense of alienation deepened, and his later works reveal a poet grappling with bitterness, solitude, and injustice.

This transformation mirrors the broader trends in 18th century French poetry, which began to move away from classical rigidity toward a more personal and emotional voice. Rousseau’s exile made him a precursor to the Romantic spirit, anticipating the inner turmoil that poets like Lamartine and Hugo would later explore in the 19th century.

Religious Themes and Spiritual Reflection

Although Rousseau’s name is closely associated with satire, he also wrote deeply religious verse. During his years of exile, he turned more frequently to spiritual themes. His odes on divine love and Christian morality reflect a troubled soul seeking redemption and peace.

This aspect of Rousseau’s work invites comparison with the devout poetry of Jean-Baptiste Gresset, another 18th century French poet who also explored religious themes but from a place of reconciliation with the church, unlike Rousseau, whose relationship with organized religion remained tense and conflicted.

Rousseau’s religious poems are contemplative, lyrical, and at times mystical. They reveal a poetic voice that was not simply cynical but also searching and vulnerable. These poems demonstrate that even a satirist can possess a profound spiritual side.

Comparison with Voltaire and Other Enlightenment Writers

Jean-Baptiste Rousseau was a contemporary of Voltaire, though their careers followed very different paths. Voltaire enjoyed both fame and influence during his lifetime, despite his own controversies with the church and the monarchy. Rousseau, by contrast, ended his days in poverty and exile.

Voltaire used satire as a tool for philosophical and social critique. His work, such as Candide, carried a larger intellectual agenda. Rousseau’s satire was more personal and emotional, more focused on exposing individual folly than systems of belief.

Rousseau did not align with the philosophes of the Enlightenment. While they promoted reason, progress, and secularism, Rousseau’s work remained tied to moral introspection, emotional struggle, and often religious longing. In this sense, Rousseau stands apart from the dominant literary currents of his time, even as he contributed to 18th century French poetry in significant ways.

Style and Language: The Craft of a French Poet

Rousseau’s style was precise, elegant, and highly structured. He mastered traditional poetic forms such as the ode, the epigram, and the elegy. His use of meter and rhyme followed the classical traditions of French poetry, but his tone was often subversive.

What made Rousseau’s verse distinctive was his combination of formality with personal bitterness. His language could be lyrical and cruel within the same stanza. His control over language reflected both intellectual discipline and emotional depth.

Unlike later Romantic poets who favored free expression, Rousseau remained loyal to formal verse structures. This duality—classical form with emotional tension—defines much of 18th century French poetry and is central to Rousseau’s work.

The Legacy of Jean-Baptiste Rousseau

Today, Jean-Baptiste Rousseau is not as widely read as Voltaire or Boileau, yet his legacy in French poetry is undeniable. He was one of the few 18th century French poets to live a truly tragic poetic life—celebrated early, condemned later, and misunderstood at the end.

His exile and defiance gave him a reputation as a poetic martyr. Some critics see him as a precursor to later poets who would suffer for their art and beliefs, such as Gérard de Nerval and Paul Verlaine.

Rousseau’s contributions to French poetry lie in his boldness. He dared to write with venom when others flattered. He sought spiritual truth while living in disgrace. His work represents a bridge between classical poetry and the coming age of Romanticism.

Rousseau in the Context of 18th Century French Poetry

To understand Rousseau’s importance, one must place him within the broader spectrum of 18th century French poets. Nicolas Boileau set the tone for literary decorum, while Voltaire carried forward the Enlightenment’s intellectual critique. Jean-Baptiste Gresset represented piety and refinement.

Rousseau, in contrast, carved a path of resistance and introspection. His poetry did not seek approval—it demanded reaction. This set him apart and ensured that his work remained relevant to those who value poetic integrity over social acceptance.

In many ways, Rousseau foreshadowed the struggles that would define 19th century French poetry: alienation, exile, passion, and the tension between personal truth and public voice.

Conclusion

Jean-Baptiste Rousseau is a figure worth rediscovering. As an 18th century French poet, he embodied the conflict between personal integrity and public consequence. His sharp satires, religious odes, and melancholic elegies form a body of work rich in contradiction and emotion.

In comparing Rousseau with his contemporaries, we find a unique voice—less rational than Voltaire, less structured than Boileau, and more tormented than Gresset. Yet all these differences contribute to the richness of 18th century French poetry.

Rousseau’s legacy teaches us that poetry is not only about beauty but also about courage—the courage to speak uncomfortable truths, to challenge powerful enemies, and to write even in exile. In this, Jean-Baptiste Rousseau remains one of the most compelling and courageous French poets of his century.