Jean Moréas, born Ioannis Papadiamantopoulos in 1856, stands as a central figure in the transformation of 19th Century French poetry. Though Greek by birth, Moréas became deeply embedded in the French literary world and made significant contributions to French poetic thought. He is best known for his early involvement in the Symbolist movement and for initiating a return to classical ideals later in his career. This article explores his life, his literary evolution, and his influence on his contemporaries, revealing his importance in the broader context of French poetry.

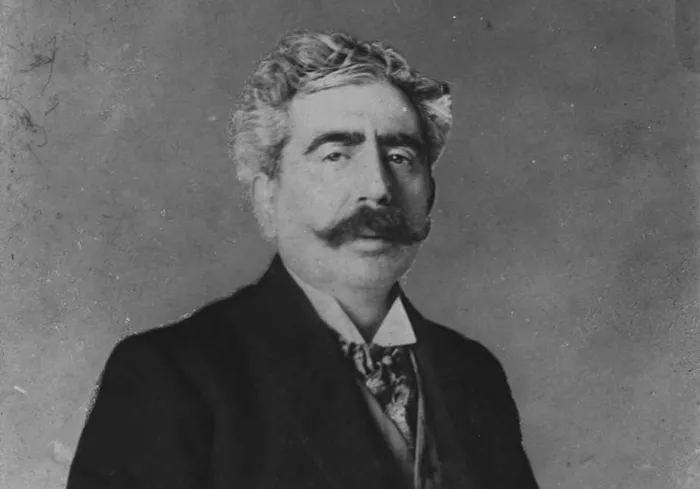

Jean Moréas

Jean Moréas was born into a prominent Greek family in Athens. His upbringing was shaped by a blend of Greek traditions and Western European culture. From an early age, he was introduced to French literature and language by a French governess. This foundation led to a lifelong love of French culture. In 1875, he moved to Paris to study law at the University of Paris. However, it was the intellectual and artistic circles of the city that would capture his attention.

Paris in the late 19th century was a hub of artistic experimentation. Writers, poets, painters, and philosophers gathered in cafés, salons, and journals to share new ideas. Moréas quickly became a regular presence in these circles. His Greek heritage gave him a unique perspective, allowing him to draw from both classical and modern sources. Though an outsider by birth, he became one of the most influential voices in French poetry.

The Symbolist Movement and Its Genesis

In the 1880s, French poetry was undergoing a dramatic transformation. The dominant schools of Romanticism and Parnassianism were losing their appeal. Poets were seeking new ways to express the inner world—feelings, visions, and the spiritual dimension of life. This search gave rise to Symbolism, a literary movement that aimed to move beyond realism and objective representation.

Jean Moréas emerged as a leader in this new movement. In 1886, he published the “Symbolist Manifesto,” which outlined the principles of Symbolism and distinguished it from Decadence, a term that was often used disparagingly by critics. In this manifesto, Moréas declared that Symbolism sought to clothe the Ideal in perceptible forms. He argued that poetry should not describe the world directly, but rather evoke it through suggestive images and symbols.

This new approach was a radical departure from the clear, objective poetry of the Parnassians. Symbolism embraced ambiguity, musicality, and metaphysical themes. Poets such as Stéphane Mallarmé, Paul Verlaine, and Arthur Rimbaud were already experimenting with similar ideas. But it was Moréas who gave the movement its theoretical foundation and its name.

Early Works and the Language of Symbols

Moréas’s early poetry reflects his Symbolist ideals. His first major collection, Les Syrtes (1884), explores mythological and dreamlike themes using rich, musical language. The poems are atmospheric rather than narrative. They seek to suggest rather than explain. The sea, twilight, ruins, and ancient landscapes are recurring motifs. These are not merely decorative images—they act as symbols for deeper truths.

In 1886, he published Les Cantilènes, a work that is often seen as one of the definitive texts of Symbolist poetry. These poems move away from the traditional structures of rhyme and meter, embracing free rhythms and incantatory repetition. The tone is often melancholic, mysterious, or ecstatic. The poet appears less as a narrator and more as a medium for a higher vision.

This aesthetic placed Moréas at the forefront of a literary revolution. By advocating for a poetry based on intuition, emotion, and the spiritual realm, he helped lay the groundwork for modernist literature in the 20th century.

The Shift Toward Classicism

Despite his initial enthusiasm for Symbolism, Moréas eventually grew dissatisfied with the direction it was taking. He believed that the movement had become too abstract and obscure. Some Symbolist poets, especially Mallarmé, were moving toward a style so hermetic that it risked losing contact with readers altogether.

In the early 1890s, Moréas made a dramatic shift in his poetic style. He began advocating for a return to classical forms, clarity, and restraint. This transformation culminated in his 1891 collection Le Pèlerin passionné, where he began to revive themes from ancient Greece and Rome. The diction became more measured, the images more concrete, and the structure more formal.

He founded a new literary group known as the “École Romane,” or Roman School, which emphasized the values of classical antiquity. This school stood in opposition to the mysticism and formlessness that some Symbolists were embracing. Moréas’s embrace of classicism was not a denial of imagination or emotion, but a belief that art should have order and proportion.

Works such as Énone au clair visage (1893), Eriphyle (1894), and the verse play Iphigénie à Aulide (1903) show his mature style. These poems and plays draw on mythology, history, and ancient drama. They are disciplined in form but still rich in symbolism. In many ways, Moréas was attempting to fuse the visionary power of Symbolism with the discipline of classical art.

Comparison with Other 19th Century French Poets

Jean Moréas’s trajectory offers a striking contrast with other major French poets of his time. Stéphane Mallarmé, for example, continued to push Symbolism toward abstraction. His later works, such as Un coup de dés jamais n’abolira le hasard, are highly experimental, even typographically. Mallarmé was concerned with the visual and conceptual aspects of poetry as much as with sound.

Paul Verlaine, by contrast, favored lyricism, emotional nuance, and personal confession. His poetry, especially in collections like Romances sans paroles, is marked by musical rhythm and tender sadness. Verlaine remained a Symbolist in many respects, but his tone was often more intimate and sensual.

Arthur Rimbaud, perhaps the most radical of all, abandoned poetry altogether in his early twenties after producing some of the most visionary texts of the century. His Illuminations and Une Saison en Enfer broke down the boundaries between prose and poetry, logic and dream.

In this context, Moréas’s journey is unique. He began as a theorist and champion of Symbolism, then rejected its extremes in favor of classical order. This move may seem conservative, but it was also a bold reimagining of poetic tradition. While others delved deeper into obscurity or introspection, Moréas sought balance—an equilibrium between imagination and structure, freedom and discipline.

Impact on French Poetry

The influence of Jean Moréas on 19th Century French poetry is significant but complex. His Symbolist period helped define a generation of poets and shaped literary journals, manifestos, and salons. By giving Symbolism a coherent identity, he allowed it to spread beyond poetry into art, music, and theater.

His later classical phase also had lasting effects. The École Romane inspired writers who believed that modern poetry had drifted too far into vagueness. Moréas’s return to clarity and mythology prefigured later movements such as Neoclassicism and even influenced early 20th-century modernist poetry, which often sought to balance innovation with a respect for tradition.

Furthermore, Moréas’s work helped bridge cultural traditions. He was a Greek writing in French, drawing on both Homer and Baudelaire, both Pindar and Hugo. His life and work demonstrate how literary traditions are not fixed by nationality but shaped by intellectual exchange.

A French Poet Beyond Borders

Though he was not French by birth, Jean Moréas is considered a French poet in the fullest sense. He wrote exclusively in French, participated in the major literary debates of his time, and helped redefine the direction of French poetry. His unique voice stands at the crossroads of cultures—Greek, French, classical, and modern.

Moréas’s international perspective enriched his poetry. He brought the philosophical rigor of ancient Greece into dialogue with the emotional depth of 19th-century France. He showed that the poetic imagination need not be confined by national boundaries or stylistic conventions. His example continues to inspire poets who seek to navigate between tradition and innovation.

Conclusion

Jean Moréas was not just a 19th Century French poet; he was a literary architect, building bridges between ideas, styles, and epochs. His role in defining and then critiquing Symbolism shows the depth of his engagement with poetic form. His later classical turn was not a retreat but a progression—a belief that poetry must both evolve and remember.

In the complex tapestry of 19th Century French poetry, Moréas is a thread of transformation. He began with mysticism and ended with harmony. His work reflects the tension and dialogue between freedom and form, inspiration and tradition. For these reasons, Jean Moréas remains an essential figure in understanding the evolution of French poetry.

Though not as widely read today as some of his peers, his legacy endures. He reminds us that poetry is both a personal and cultural act—an expression of the inner world shaped by the ideals of the outer one. Through his work, we hear the echoes of ancient voices made modern once more, and we are invited to explore the vast possibilities of poetic expression.