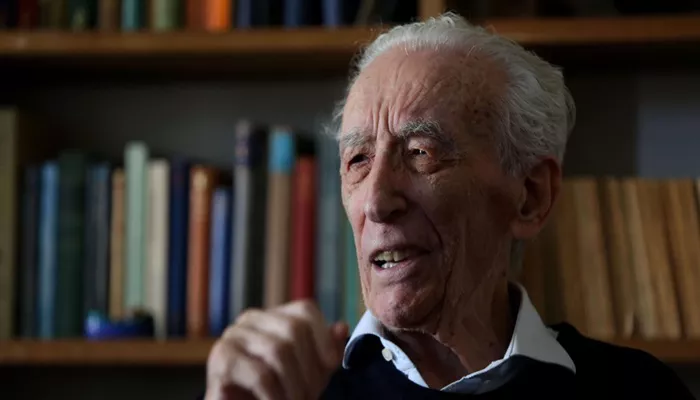

In the vast landscape of 20th century Italian poets, Franco Loi holds a significant position for his unique linguistic choices and emotional depth. Born in Genoa in 1930 and raised in Milan, Loi contributed to Italian poetry by crafting verses in the Milanese dialect, bringing regional language to the national stage. His work represents a bridge between the past and the present, reflecting Italy’s historical turbulence and cultural richness. As an Italian poet who dared to write beyond standard Italian, Loi expanded the possibilities of poetic expression in Italy during a century marked by war, reconstruction, and social change.

The Historical Context of Italian Poetry in the 20th Century

The 20th century was a time of great upheaval and transformation in Italy. The two World Wars, the rise and fall of Fascism, and the economic boom of the 1950s and 60s shaped Italian literature profoundly. Italian poetry during this time responded to these events with urgency and introspection. Poets sought to redefine their identity and the language they used, often turning to experimental forms and regional voices.

Early in the century, poets like Giuseppe Ungaretti, Eugenio Montale, and Salvatore Quasimodo established a foundation of modernist expression that combined symbolism, hermeticism, and existential inquiry. These figures are often considered the giants of 20th century Italian poetry. However, the mid to late century saw a diversification of voices and themes, and it is in this context that Franco Loi emerged.

Biography and Influences

Franco Loi’s poetry cannot be separated from his personal background and the sociopolitical context of his time. Born in 1930 to a Sardinian father and a Ligurian mother, Loi moved to Milan at a young age. The industrial capital of northern Italy became not only his home but also the soul of his poetic landscape.

After leaving school early, Loi worked in various professions before becoming involved in publishing. He began writing poetry relatively late, with his first major collection, Stròlegh, appearing in 1975. By this time, he was already 45 years old. Yet the delay in publication was not a hindrance to his creativity; rather, it marked the beginning of a mature and introspective poetic journey.

Loi was heavily influenced by the classical and modernist traditions, but he turned away from the academic style that dominated post-war Italian poetry. Instead, he focused on language as lived experience. The Milanese dialect, often dismissed as too colloquial or unrefined for serious literature, became his poetic medium. This choice aligned him with other regional writers who resisted the homogenization of Italian culture and language in the wake of national unification and mass media expansion.

The Milanese Dialect and Vernacular Poetry

Loi’s use of dialect is perhaps his most distinctive feature. Italian poets in the 20th century often grappled with the challenge of finding a language that could carry both the weight of history and the intimacy of personal expression. For Loi, the Milanese dialect was not merely a linguistic choice; it was a political and aesthetic decision.

Dialect allowed him to speak with the voice of ordinary people, to capture the rhythms of everyday life, and to preserve the memory of a disappearing world. In doing so, he challenged the elitism of literary Italian and elevated the vernacular to the level of high art. This approach connects him with poets such as Pier Paolo Pasolini, who also wrote in dialect and emphasized the authenticity of regional cultures.

Loi believed that language carried memory and identity. Through the Milanese dialect, he accessed a collective memory that included the working-class struggles, wartime trauma, and post-war optimism of northern Italy. His poems often read like oral histories—personal yet universal, lyrical yet grounded.

Major Works and Themes

Loi’s poetry collections span several decades and demonstrate remarkable consistency in voice and vision. His debut volume, Stròlegh, established his signature style: free verse, dialectic language, and a deep engagement with history and memory. The title refers to a kind of folk healer or fortune teller, suggesting the poet’s role as one who uncovers hidden truths.

In Teater (1978), Loi explores the theatricality of social life and the performative aspects of identity. His characters are often ordinary people—workers, neighbors, children—who become symbols of broader human experiences. The poems in this collection blend humor and sorrow, realism and myth.

L’Angel (1981) delves into spiritual and metaphysical questions, reflecting Loi’s interest in religion and mysticism. While rooted in Catholic imagery, these poems also express a deep longing for transcendence and meaning in a fragmented world.

Throughout his career, Loi returned to certain key themes: the passage of time, the nature of memory, the endurance of suffering, and the possibility of redemption.

His work reflects a moral seriousness without becoming didactic. He saw poetry as a form of testimony—a way to bear witness to both personal and collective histories.

Comparison with Contemporary Poets

In comparing Franco Loi to his contemporaries, one notices both similarities and significant differences. Like Eugenio Montale, Loi was concerned with the alienation of modern life and the search for spiritual meaning. However, while Montale’s language was dense and often allusive, Loi’s was direct and rooted in spoken tradition.

Giuseppe Ungaretti, another major figure among 20th century Italian poets, shared Loi’s belief in the expressive power of stripped-down language. Yet Ungaretti wrote in a highly stylized version of Italian, whereas Loi chose dialect. This distinction underscores their differing views on the relationship between language and identity.

Pier Paolo Pasolini, mentioned earlier, perhaps comes closest to Loi in terms of sensibility and technique. Both poets wrote in dialect, were politically engaged, and viewed poetry as a form of cultural resistance. Pasolini’s Friulian poems and Loi’s Milanese verses stand as parallel projects that celebrate regional voices in a national literary context.

Andrea Zanzotto, another contemporary, also explored dialect and experimental language. But Zanzotto’s work often leaned toward abstraction and linguistic play, while Loi remained firmly anchored in the tangible realities of daily life.

Political and Ethical Dimensions

Franco Loi was not only a poet but also a public intellectual. His political beliefs, shaped by the post-war Italian left, infused his work with a strong ethical commitment. He believed that poetry could illuminate social injustice and contribute to a more humane society.

However, Loi did not write propaganda. His politics were embedded in the human stories he told. By giving voice to marginalized individuals and communities, he highlighted the dignity of ordinary lives. His poems evoke empathy rather than outrage, contemplation rather than confrontation.

This ethical stance connects him with the broader tradition of 20th century Italian poets who saw literature as a moral endeavor. In the wake of Fascism and war, many poets turned to art as a means of reconstruction—not just of buildings and institutions, but of the human spirit.

Reception and Legacy

Franco Loi’s work received critical acclaim both in Italy and abroad. He won several major literary prizes and was often invited to speak at universities and literary festivals. Yet he remained somewhat on the margins of mainstream Italian literature, partly because of his use of dialect and his resistance to fashionable trends.

Today, scholars and readers are rediscovering his poetry as an essential part of 20th century Italian literature. His work offers valuable insights into the cultural and linguistic diversity of Italy, as well as the enduring power of poetic expression. In an era of globalization and cultural homogenization, Loi’s commitment to local identity and memory is particularly resonant.

His influence can be seen in younger poets who experiment with dialect and explore the intersections of language, place, and identity. By demonstrating that poetry could be both personal and political, both regional and universal, Franco Loi helped to expand the horizons of Italian poetry.

Conclusion

Franco Loi stands as a remarkable figure among 20th century Italian poets. Through his use of the Milanese dialect, he redefined what it meant to be an Italian poet. His work speaks to the complex realities of modern life while preserving the voices and memories of a vanishing world.

In a century marked by rapid change and cultural conflict, Loi’s poetry offers a model of rootedness and resilience. He reminds us that language is not just a tool for communication but a vessel for memory, identity, and transformation. As Italian poetry continues to evolve in the 21st century, the legacy of Franco Loi will remain a touchstone for those who seek to write with integrity, compassion, and truth.

By celebrating the local, he touched the universal. By writing in dialect, he spoke to the soul. And in doing so, Franco Loi secured his place in the pantheon of 20th century Italian poets.