19th century was a time of transformation for French poetry. The Romanticism of Victor Hugo and Alphonse de Lamartine gave way to new movements such as Parnassianism and Symbolism. Among the prominent figures of this transitional era was Charles-Marie-René Leconte de Lisle, a poet whose work stood out for its classical precision, exotic imagery, and intellectual depth. As a leading voice of the Parnassian school, Leconte de Lisle rejected the emotional excesses of Romanticism and emphasized formal discipline and impersonal beauty in poetry.

Leconte de Lisle’s poetry offers a rich perspective on art, nature, myth, and history. This article will explore his life, poetic ideals, key works, stylistic features, and influence, while comparing him with his contemporaries in 19th-century French poetry.

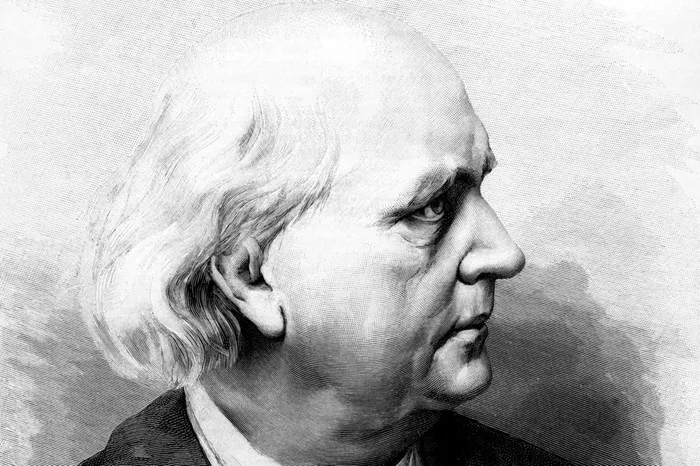

Charles-Marie-René Leconte de Lisle

Charles-Marie-René Leconte de Lisle was born on October 22, 1818, on the island of La Réunion, a French colony in the Indian Ocean. His upbringing in this lush and exotic environment would later inform the sensual and tropical imagery in his poems. At the age of fifteen, he was sent to France to study, eventually attending the Collège de Saint-Denis and later the University of Rennes.

Originally drawn to political activism, Leconte de Lisle participated in republican movements during the 1848 Revolution. However, he grew disillusioned with politics and turned instead to literature. His early experiences, both colonial and continental, shaped his worldview and poetic voice, fusing a reverence for classical antiquity with a fascination for distant lands and ancient civilizations.

The Rise of the Parnassian School

In the mid-19th century, French poetry was evolving. The dominance of Romanticism, with its emotional fervor and subjective voice, began to face criticism. A group of poets sought a more detached and structured aesthetic. Leconte de Lisle became a key figure in this movement.

The Parnassian school, named after the 1866 anthology Le Parnasse Contemporain, advocated for “art for art’s sake” (l’art pour l’art). Poets in this school valued form, clarity, and restraint. They believed poetry should be beautiful and intellectual, not a vehicle for personal emotion or political ideology.

Leconte de Lisle was the spiritual leader of the Parnassians. His poetic philosophy emphasized the timeless and the universal. Like a sculptor, he carved verses with precision, eschewing the confessional mode of the Romantics. He once remarked that poetry should reflect the grandeur of the universe and the immortality of human achievements, not transient feelings.

Major Works

Poèmes antiques (1852)

This collection marked Leconte de Lisle’s emergence as a serious French poet. Poèmes antiques explores Greek and Roman mythology, history, and philosophy. The poems are rich in allusions to classical texts and are written in a stately, dignified tone. Leconte de Lisle paints a world of gods, heroes, and ancient rituals, portraying them with both sensuality and detachment.

One notable poem, “La Mort de Sardanapale,” revisits the Assyrian king’s extravagant suicide, echoing Eugène Delacroix’s famous painting. Leconte de Lisle does not moralize; he presents the scene as an aesthetic tableau—lush, violent, and timeless.

Poèmes barbares (1862)

In this collection, Leconte de Lisle expanded his focus beyond the Greco-Roman world. Poèmes barbares delves into Indian, Nordic, Polynesian, and African myths. Here, he explores the human condition through non-European lenses, though still with a classical eye.

The poem “Le Manchy” offers a lyrical rendering of Hindu mythology, while “Qaïn” reflects on the biblical figure of Cain, presenting him as a symbol of existential isolation. These poems are deeply philosophical, often meditating on death, fate, and the cruelty of nature.

Poèmes tragiques (1884)

This later work is darker and more introspective. The tone shifts from the majestic to the mournful. Poèmes tragiques examines the futility of human ambition and the inevitability of death. Leconte de Lisle presents life as governed by natural law, not divine providence.

In the poem “L’Orestie,” based on the Oresteia of Aeschylus, the tragic weight of inherited guilt is explored. The classical form remains, but the emotional resonance is more somber. This collection can be seen as the poet’s mature reflection on suffering and mortality.

Style and Technique

Leconte de Lisle’s style is distinguished by formal rigor, visual richness, and historical scope. He employed alexandrine verse—the classical twelve-syllable line favored in French poetry—with exceptional mastery. His language is precise and musical, carefully structured to achieve balance and harmony.

Unlike Romantic poets, Leconte de Lisle used impersonal diction. He rarely employed the first person, preferring third-person narration or objective description. This created a sense of emotional distance and timelessness.

His use of imagery is another key feature. Drawing from his colonial background and classical education, he described landscapes, mythological scenes, and rituals in vivid detail. Whether portraying an Egyptian temple or an Arctic wilderness, he rendered scenes with the eye of a painter.

Leconte de Lisle also made frequent use of allusion. Readers of his work often need familiarity with Greek tragedy, Sanskrit epics, or ancient history to fully appreciate the depth of meaning. Yet the musicality and grandeur of his language often transcend these scholarly boundaries.

Comparison with Contemporaries

Victor Hugo

Victor Hugo, the towering figure of 19th century French poetry, was the antithesis of Leconte de Lisle. Hugo’s Romanticism was passionate, political, and lyrical. His verse pulsated with emotion and personal conviction.

Where Hugo saw poetry as a tool for moral engagement, Leconte de Lisle viewed it as a temple of beauty. Hugo addressed social injustices in poems like Les Châtiments, while Leconte de Lisle remained aloof, preferring myth to manifesto.

Yet both poets were masters of the French language. Hugo’s dynamism and Leconte de Lisle’s sculptural clarity represent two poles of poetic excellence in the same century.

Charles Baudelaire

Another crucial figure in French poetry was Charles Baudelaire, whose Les Fleurs du mal (1857) revolutionized poetic themes and forms. Like Leconte de Lisle, Baudelaire was dissatisfied with Romanticism. However, Baudelaire embraced subjectivity, decadence, and urban modernity, whereas Leconte de Lisle looked to the ancient and the eternal.

Baudelaire’s imagery was sensual and often morbid. Leconte de Lisle’s was idealized and monumental. Both contributed to the transition toward Symbolism, but from different aesthetic and philosophical angles.

Stéphane Mallarmé and the Symbolists

Leconte de Lisle’s influence is also visible in the Symbolist movement. Poets like Stéphane Mallarmé admired his craftsmanship and attention to language. However, Symbolism moved away from clarity toward suggestion and mystery.

Where Leconte de Lisle sculpted meaning in marble, Mallarmé dissolved it into mist. Nonetheless, the Parnassians paved the way for Symbolists by restoring poetic discipline and emphasizing the power of pure form.

Philosophical and Aesthetic Influences

Leconte de Lisle’s work is informed by materialism, determinism, and a reverence for classical antiquity. He was influenced by the philosophies of Lucretius and the Stoics, viewing the universe as governed by natural laws, not divine will.

In many poems, nature is indifferent, even cruel. Yet this cruelty has its own sublime beauty. Leconte de Lisle did not seek solace in religion or romantic love. Instead, he found meaning in the artistic contemplation of existence. This gives his work a dignified austerity, a quiet grandeur.

His aesthetic theory can be summarized in the phrase impersonal beauty. He believed that the poet’s role was to reveal the eternal patterns beneath surface chaos. Art was not an expression of the self, but a mirror of the cosmos.

Legacy and Influence

Charles-Marie-René Leconte de Lisle played a crucial role in shaping French poetry in the second half of the 19th century. His advocacy for formal discipline and classical subjects influenced generations of poets.

As editor of Le Parnasse Contemporain, he helped launch the careers of many younger writers. He also translated ancient Greek works, including those of Aeschylus, Homer, and Sophocles, thereby contributing to the revival of classical literature in France.

Though the rise of Symbolism eventually eclipsed Parnassianism, Leconte de Lisle remained a respected figure. In 1886, he was elected to the Académie Française, a testament to his stature as a 19th century French poet.

In the 20th century, his reputation waned as modernist poets rejected classical forms. Yet in recent decades, scholars have reassessed his contribution. His meticulous verse, philosophical depth, and intercultural range now receive renewed appreciation.

Conclusion

Charles-Marie-René Leconte de Lisle was more than a poet; he was an architect of language and thought. In an age of political upheaval and literary experimentation, he offered a vision of stability, order, and transcendence. His work invites readers to contemplate the eternal through the lens of myth, history, and nature.

As a leading 19th century French poet, Leconte de Lisle carved out a space between Romantic passion and Symbolist mysticism. His poems endure as monuments of precision and grandeur in French poetry. He reminds us that beauty can be impersonal, that form can convey truth, and that poetry can be a timeless mirror of human dignity.