Pierre Emmanuel stands as one of the most compelling voices in 20th Century French poetry. His works reflect the spiritual crisis of modernity, the experience of war, and a search for transcendence. As a French poet, Emmanuel combined Christian mysticism, existential questioning, and lyrical intensity. He was deeply engaged in the political and moral issues of his time. Alongside poets such as Paul Éluard, René Char, and Saint-John Perse, he shaped the cultural and ethical landscape of post-war France. However, Emmanuel remains somewhat underappreciated compared to his contemporaries. This article aims to explore his life, poetic vision, and influence, while situating him within the broader context of French poetry in the 20th century.

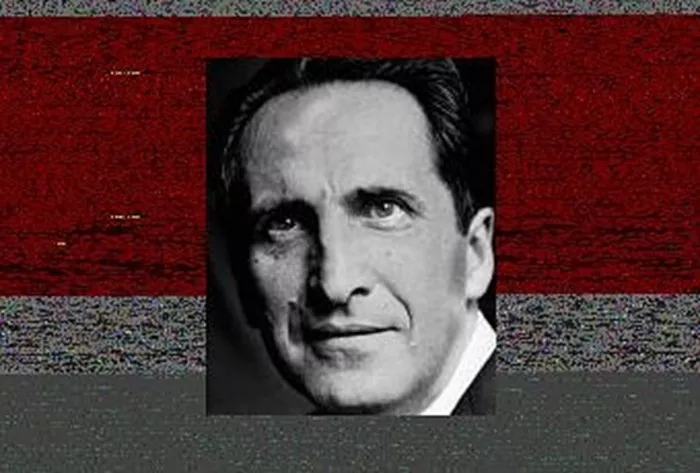

Pierre Emmanuel

Pierre Emmanuel was born Noël Mathieu in 1916 in the city of Gan, in the Pyrenees region. He adopted the pseudonym “Pierre Emmanuel” as a poetic identity, a common practice among 20th Century French Poets. He came from a modest background and studied literature and philosophy. From a young age, he was drawn to poetry, classical literature, and the spiritual texts of Christianity.

His intellectual influences included Blaise Pascal, Saint Augustine, and the French symbolist poets. This mixture of religious fervor and literary refinement laid the groundwork for his poetry. During the 1930s, Emmanuel began publishing his poems, quickly gaining attention for their intense, lyrical, and metaphysical style.

The Role of Faith and Spirituality

Emmanuel’s poetry is marked by a persistent engagement with Christian theology and mystical thought. Unlike secular or political poets of his generation, Emmanuel turned to spiritual themes to address the anguish of existence and the horror of war. For him, poetry was not merely an aesthetic exercise but a vocation—a spiritual calling.

In his early collections, such as Élégies (1940) and Jour de colère (1943), Emmanuel expressed sorrow and outrage at the condition of humanity, especially in the context of World War II. The Holocaust, the occupation of France, and the decline of moral values led him to write poetry that was both prophetic and penitential. His belief in the redemptive power of language set him apart from more nihilistic or surrealist trends in French poetry.

Poetic Style and Themes

Pierre Emmanuel’s poetic style is characterized by its grandeur, oratorical rhythm, and biblical resonance. His use of free verse, symbolic imagery, and liturgical vocabulary gives his work a timeless, sacred tone. Unlike André Breton or other 20th Century French Poets who experimented with automatic writing, Emmanuel wrote with careful structure and theological intention.

Themes commonly found in his work include:

Spiritual exile and return

The crisis of modernity

Sacrificial love

The search for divine grace

Human dignity in the face of evil

In Le Poète et son Christ (1959), Emmanuel proposes a vision of poetry as a path to the divine, aligning the poet’s suffering with Christ’s passion. This religious metaphor underscores his belief in the poet as an intercessor between humanity and the divine.

World War II and Resistance Poetry

During World War II, Pierre Emmanuel became an important voice of literary resistance. Like René Char and Paul Éluard, he refused to remain silent during the Nazi occupation of France. His collection Jour de colère (Day of Wrath) was a direct response to the atrocities of the time.

This period marked a turning point for Emmanuel. He saw poetry as an act of moral witness. His words became weapons of resistance and hope. While Char’s poetry embraced ambiguity and surrealism, Emmanuel’s voice remained prophetic, drawing on Old Testament wrath and apocalyptic imagery.

In contrast to surrealist or existentialist poets, Emmanuel offered a spiritual reading of the war. He did not romanticize suffering. Instead, he viewed it through the lens of Christian theology, suggesting that suffering could be redemptive when aligned with divine justice.

Relationship with Other French Poets

Pierre Emmanuel’s career intersected with several major 20th Century French Poets. While he shared common ground with figures like Paul Claudel and Charles Péguy in terms of Christian inspiration, he was also dialoguing with poets of radically different orientations.

Paul Éluard: A Communist and surrealist, Éluard focused on love and freedom. Emmanuel admired his courage during the war but distanced himself from his political materialism.

René Char: A poet of the Résistance and metaphysical imagery, Char influenced Emmanuel with his austere vision of poetic truth. However, Emmanuel’s theological framework made his voice more anchored in tradition.

Saint-John Perse: Known for his grand, ceremonial verse, Saint-John Perse shared with Emmanuel a concern for the sacred, though Perse’s sense of the sacred was more universal and less explicitly Christian.

Thus, while Emmanuel belonged to the same poetic generation, his unique fusion of lyricism and spirituality placed him in a solitary position. He was respected, but also somewhat isolated within the French poetry scene.

Institutional Influence and Literary Recognition

Pierre Emmanuel was not only a French poet, but also an institutional figure in French literary culture. After the war, he worked as a literary advisor and held influential roles in organizations like UNESCO. He served as President of PEN International and was elected to the prestigious Académie française in 1968.

His appointment to the Académie française was significant. It marked the recognition of spiritual and ethical poetry in a century often dominated by experimental and political poetics. Emmanuel used his platform to defend freedom of expression and promote intercultural dialogue.

In his later years, he also became involved in public debates on education and literature. He believed that poetry should be central to human education, a belief reminiscent of ancient and medieval traditions.

Later Works and Maturity

In his later collections, such as Le Goût de l’un (1977) and La Nouvelle Naissance (1973), Pierre Emmanuel reached a state of spiritual maturity. These poems reflect a mystical joy, a deep communion with the divine, and a visionary understanding of time and history.

He moved away from the anger and despair of his wartime poems and embraced a tone of reconciliation and transcendence. Nature, love, and silence became new motifs. This evolution mirrors the path of a mystic, moving from darkness to light, from protest to peace.

One of his most ambitious works is Le Livre de l’Homme et de la Femme (1957), a poetic cycle exploring the archetypes of human love, gender, and divine union. Inspired by the Song of Songs and Jungian psychology, this collection stands as a synthesis of his major themes.

Comparative Analysis with Christian Poets

To better understand Emmanuel’s place in 20th Century French poetry, it is helpful to compare him with Christian poets of other countries.

T. S. Eliot (England): Like Emmanuel, Eliot was deeply Christian, especially in his later works such as Four Quartets. Both poets viewed history as spiritually significant and saw poetry as a form of prayer.

Paul Claudel (France): Claudel’s baroque, liturgical language influenced Emmanuel. Yet Emmanuel was more modern in tone, less theatrical, and more attuned to existential doubt.

Rainer Maria Rilke (Germany/Austria): Rilke’s Duino Elegies and Sonnets to Orpheus are spiritual but less theological. Emmanuel, by contrast, explicitly affirms Christian doctrine.

These comparisons highlight Emmanuel’s unique balance: he was both a mystic and a modern. He accepted the brokenness of the world while still pointing toward transcendence.

Legacy and Relevance Today

Pierre Emmanuel died in 1984, but his influence endures. His poetry offers a rare combination of lyrical beauty, moral seriousness, and metaphysical vision. In a world marked by secularism and cynicism, his voice calls readers back to the sacred dimensions of language and life.

His legacy can be seen in contemporary poets who seek a spiritual renewal in literature. Writers like Jean Grosjean, Jean Mambrino, and Christian Bobin have acknowledged Emmanuel as a guide.

In academic circles, there is a renewed interest in his work. Scholars of French poetry have begun to reassess his contributions, especially in light of ecological theology, post-war ethics, and religious poetics.

Conclusion

Pierre Emmanuel remains a towering figure in 20th Century French poetry. As a French poet, he embodied the conscience of a century ravaged by war, ideological conflict, and spiritual loss. Yet, he never abandoned hope. His poetry urges humanity toward justice, love, and the divine.

His life and works serve as a reminder that poetry can be both a song and a sword—a means of inner transformation and public witness. In an age still searching for meaning, Emmanuel’s verse offers the clarity of a prophetic voice and the tenderness of a believer.

His contribution to French poetry deserves greater recognition, not only for its literary merit but for its enduring moral and spiritual depth. Pierre Emmanuel is not merely a poet of the past; he is a poet for all time.