Among the major figures of modern literature, Saint-John Perse stands as a towering presence in 20th century French poetry. A Nobel Laureate, a seasoned diplomat, and a poet of epic scope, Perse offers readers an ambitious and mystical vision of human existence. His work stands apart in the French literary canon for its philosophical grandeur, rich language, and ceremonial tone. As a 20th Century French poet, Perse blended the spiritual with the political, the mythological with the historical, and the lyrical with the abstract. His poetry resists easy classification, yet its lasting influence is evident in both French poetry and global literary traditions.

This article will provide a comprehensive exploration of the life, literary career, and poetic significance of Saint-John Perse. It will contextualize his work within the broader landscape of 20th century French poetry, drawing comparisons to contemporaries such as Paul Valéry, Paul Claudel, and René Char. We will also examine the impact of his diplomatic background on his poetry, and the symbolic and stylistic features that define his unique voice. Throughout, we will consider how Perse’s contribution continues to shape our understanding of the French poet’s role in the modern era.

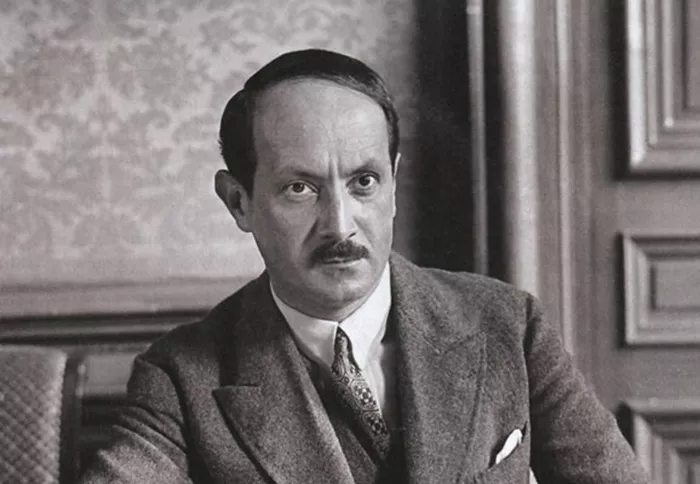

Saint-John Perse

Saint-John Perse was born as Alexis Léger on May 31, 1887, in Pointe-à-Pitre, Guadeloupe. This Caribbean origin played a profound role in shaping his sensibility. The exotic flora, maritime horizons, and colonial tensions of the Antilles left an indelible mark on the young poet’s imagination. Though born in a French colony, Perse’s early exposure to natural beauty and cultural complexity would later become a wellspring of imagery in his poems.

Following political unrest in Guadeloupe, the Léger family moved to France in 1899. Perse studied law and political science at the University of Bordeaux and later attended the École des Hautes Études in Paris. Although he initially pursued a legal and diplomatic career, poetry remained a silent yet powerful companion. His dual engagement in political and poetic spheres became one of the defining features of his career.

The Poet and the Diplomat: A Life Between Two Worlds

Saint-John Perse led a double life: by day, he was Alexis Léger, the respected diplomat; by night, he became Saint-John Perse, the poet of elemental forces and prophetic voice. As General Secretary of the French Foreign Office under Aristide Briand, Perse was deeply involved in interwar diplomacy. He represented France in major international negotiations and was a staunch advocate for the League of Nations.

However, his refusal to cooperate with the Vichy regime during World War II led to his exile. He relocated to the United States, where he worked for the Library of Congress. It was during this exile that Perse wrote some of his most significant poetic works, affirming his identity as a French poet even while physically distant from France.

Unlike many poets who retreat from politics, Perse found a way to merge the grandeur of statecraft with the grandeur of poetic expression. The tension between diplomacy and poetry, the public and private self, is key to understanding his work. In this sense, Perse was not merely a poet who dabbled in politics; he was a statesman who articulated his vision through poetry.

Style and Themes: The Ceremony of Language

Saint-John Perse’s poetic style is highly distinctive. His works are written in free verse, yet they are anything but formless. His lines are often long, rolling, and ceremonial, echoing the rhythms of oratory and liturgy. He avoids rhyme and regular meter, preferring instead a musicality born from repetition, alliteration, and syntactic parallelism.

The language of Perse’s poetry is elevated, archaic, and richly symbolic. He draws from a lexicon of myth, science, botany, and geography to construct an expansive vision of the world. His images are often abstract, yet they carry a sensuous weight that draws readers into a heightened state of awareness. This poetic language is not intended for casual reading; it demands attention and contemplation.

Central themes in Saint-John Perse’s poetry include

Exile and journey: As in Anabase, where the poetic voice reflects on leadership, destiny, and spiritual voyage.

Nature and cosmos: Elements like wind, fire, and ocean recur throughout his work, reflecting both outer landscapes and inner transformation.

Civilization and history: In works like Chronique and Vents, Perse engages with the fate of societies and the grandeur of human aspiration.

Silence and speech: Perse explores the power of language, but also the sacredness of silence, in moments of poetic revelation.

His work invites comparison to prophetic traditions in poetry—Whitman’s inclusiveness, Claudel’s Catholic mysticism, and the oracular tone of Hölderlin.

But Perse remains uniquely himself: a French poet whose language is both rooted in literary tradition and explosively original.

Major Works and Their Impact

Éloges (1911)

This early work introduced many of the key themes and stylistic elements that would define Perse’s later poetry. Composed during his early diplomatic career, Éloges celebrates the poet’s childhood in Guadeloupe. It is filled with sensual imagery and a sense of lost paradise. The poems do not mourn exile; instead, they transform memory into myth.

In Éloges, one finds the seed of Perse’s poetic ethos: the search for origin, the fusion of inner and outer worlds, and the ceremonial tone that invites readers into a poetic ritual.

Anabase (1924)

Published under the pseudonym Saint-John Perse and with a preface by T.S. Eliot in the English translation, Anabase marks Perse’s poetic maturity. The poem is a metaphysical journey, blending the voice of a warrior-king with that of a visionary prophet. It speaks of conquest, decay, and spiritual insight.

Anabase was highly influential, particularly in the English-speaking world. T.S. Eliot praised its abstract majesty, and the poem became a model for modernist poetic ambition. Here, the French poetry tradition intersected with a modernist aesthetic, proving that the French poet could still speak with universal authority.

Exil (1942) and Poème à l’étrangère (1943)

Written during his American exile, these poems reflect Perse’s physical and emotional distance from France. Exil is a passionate defense of the poet’s autonomy and a lament for the collapse of civilization in wartime. Yet, it does not succumb to despair. Instead, it asserts the power of poetic vision to transcend borders.

In Poème à l’étrangère, Perse speaks to a feminine figure, who represents both love and loss. This work reveals a more intimate dimension of the 20th Century French poet, yet it maintains the grand style for which he is known.

Vents (1946) and Amers (1957)

These two works, among Perse’s most acclaimed, explore elemental forces. Vents deals with wind as both a natural and metaphysical force, linking weather to history and spirit. Amers, often considered his masterpiece, focuses on the sea. It is a celebration of movement, freedom, and poetic navigation.

In both works, Saint-John Perse refines his style to its highest form. The poet becomes a seer who speaks of civilizations past and future, of inner truths mirrored in the elements. Here, the French poet does not merely describe nature; he becomes one with it.

Comparison with Other 20th Century French Poets

To fully understand Saint-John Perse’s significance, it is important to compare him with other major figures in 20th century French poetry.

Paul Valéry

Valéry, like Perse, was deeply interested in the intellectual dimension of poetry. His work often emphasizes form, thought, and clarity. However, Valéry was more restrained, more analytical. Perse, by contrast, embraced a visionary tone and a more expansive, mythic approach.

Paul Claudel

Claudel’s Catholicism and theatricality offer another point of comparison. Both poets viewed poetry as a sacred act. But Claudel’s work is anchored in religious faith, while Perse’s vision is more elemental and philosophical. Perse’s cosmos is not ordered by doctrine, but by mystery and poetic insight.

René Char

Char’s poetry is marked by its resistance and political engagement, particularly during the Nazi occupation of France. His language is often cryptic, intense, and fragmented. While Char is a poet of rupture, Perse is a poet of continuity. Yet both emphasize the ethical responsibility of the poet in times of crisis.

The Nobel Prize and Late Recognition

In 1960, Saint-John Perse was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature. The Nobel Committee cited “the soaring flight and evocative imagery of his poetry.” This recognition came as a late but powerful affirmation of his work. By then, Perse was an elder statesman of French poetry, revered for his integrity, dignity, and visionary language.

His Nobel Lecture, titled La Poésie, articulated his belief in the sacred nature of poetry. For Perse, poetry was not a luxury but a necessity—a means of reconciling the human spirit with the world’s complexity. He affirmed that the French poet must not isolate himself from the world but must instead seek to illuminate it through language.

Influence and Legacy

Saint-John Perse’s influence extends beyond French poetry. His work has inspired poets, critics, and philosophers across languages. In the United States, poets like Wallace Stevens and Robert Duncan admired his abstract and elevated style. In Latin America, figures such as Octavio Paz and Pablo Neruda acknowledged his visionary power.

In France, his reputation remains somewhat complex. His poetry is often seen as difficult, distant, and elitist. Yet this very difficulty is also what gives it its lasting value.

In an age of fast consumption and surface meaning, Saint-John Perse remindsrench poet is marked by a refusal to simplify. He resisted popular trends, ideological constraints, and aesthetic fashions. Instead, he sought a timeless voice, rooted in the French language but resonating far beyond it.

Conclusion

Saint-John Perse remains a singular figure in the history of 20th century French poetry. He stands at the intersection of poetry and diplomacy, tradition and modernity, myth and reality. His work reminds us that the French poet can still aspire to grandeur—not as a matter of ego, but as a commitment to vision, language, and the mystery of existence.

While much of contemporary poetry turns toward the personal and the fragmented, Saint-John Perse offers a different path. He shows that poetry can still speak of civilizations, oceans, winds, and stars—not as metaphors, but as realities that shape our souls.

In the age of globalization, the legacy of this 20th Century French poet takes on new relevance. His language, his vision, and his commitment to the poetic act offer a model for how art can elevate human thought. As readers return to his work, they do not find easy answers, but they encounter the full power of poetic speech.

Saint-John Perse, the French poet of wind and exile, of sea and silence, continues to sail across the literary horizon, his voice a steady compass for those who seek meaning in the vast world of words.