Among the significant voices of Russian poetry in the 20th century, one finds Lydia Chukovskaya—better known for her prose and literary criticism, yet whose poetic output and literary stance place her squarely among the most courageous and ethically grounded writers of her generation. Although she is often overshadowed by more widely recognized Russian poets such as Anna Akhmatova and Marina Tsvetaeva, Chukovskaya’s life and work form an indispensable chapter in the evolution of 20th century Russian poets.

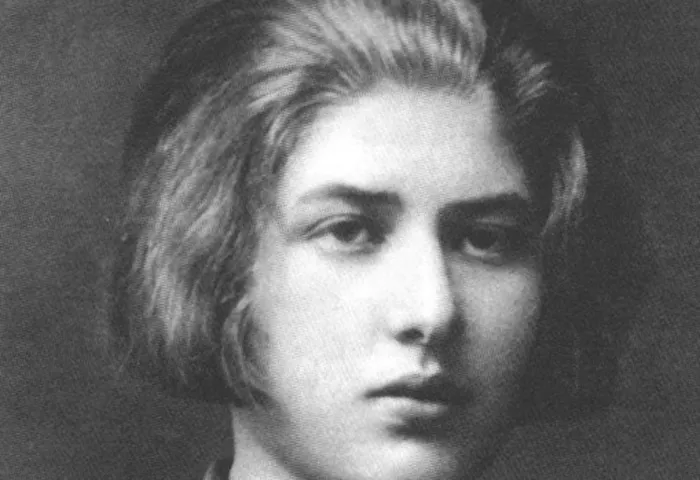

Chukovskaya’s significance lies not only in the words she wrote, but also in the moral clarity with which she confronted the tragedies of her time. Born in 1907 into a prominent literary family—her father was the noted children’s writer Kornei Chukovsky—she was exposed to literature and the Russian intelligentsia from an early age. Her proximity to major figures in Russian poetry gave her a deep understanding of literary tradition, which she carried with her throughout her life.

The Context of Russian Poetry in the 20th Century

To understand Chukovskaya’s role, it is necessary to consider the larger picture of Russian poetry during the 20th century. This was a period marked by revolution, repression, war, and ideological turmoil. The early decades of the century saw a flourishing of creativity, with movements like Symbolism, Acmeism, and Futurism shaping Russian poetic thought. Poets such as Alexander Blok, Osip Mandelstam, and Velimir Khlebnikov experimented with language and metaphysics, giving voice to a culture in upheaval.

However, the rise of Soviet power brought new constraints. By the 1930s, Socialist Realism became the mandated artistic doctrine, and many poets were silenced, imprisoned, or killed. Mandelstam died in a labor camp. Tsvetaeva committed suicide after returning to a country that no longer welcomed her. Even Akhmatova, though she survived, was subject to surveillance and censorship.

In this landscape, Lydia Chukovskaya emerged not only as a poet but as a witness and chronicler of suffering. Her role in preserving and defending the work of persecuted poets places her at the moral center of 20th century Russian literature.

Lydia Chukovskaya: A Life Bound to Literature and Resistance

Chukovskaya’s early career was shaped by her editorial work at Detgiz, a major Soviet publishing house. However, she was dismissed during Stalin’s purges, and her husband, physicist Matvei Bronstein, was arrested and executed in 1938. This personal tragedy defined much of her later work.

Although she wrote some poetry, she is best known for her novella Sofia Petrovna, a powerful depiction of life during the Great Terror. Written in 1939 and circulated in samizdat (underground press), the book remained unpublished in the Soviet Union for decades. In this and other works, Chukovskaya gave voice to the silenced, becoming a moral witness to the suffering inflicted by totalitarianism.

Her poetry, though less extensive than her prose, is marked by a quiet intensity. It often deals with themes of silence, memory, and resistance. Unlike the flamboyant style of the Futurists or the lush imagery of the Symbolists, Chukovskaya’s verse is spare and contemplative. It speaks not from the center of public life but from the margins, where truth is whispered rather than declared.

Comparison with Contemporaries

To place Chukovskaya within the tradition of 20th century Russian poets, it is helpful to compare her to her peers. Anna Akhmatova, a close friend and confidante, was a towering figure in Russian poetry. Both women shared a commitment to artistic integrity and a refusal to bend to political pressure. Akhmatova’s Requiem and Chukovskaya’s Sofia Petrovna are often read together as twin responses to Stalinist terror—one in verse, the other in prose.

Marina Tsvetaeva, another contemporary, wrote with a fierce independence and tragic vision. Her poetry, full of mythic and emotional intensity, contrasts with Chukovskaya’s more restrained style. Where Tsvetaeva burns, Chukovskaya bears witness. Both were deeply affected by exile and loss, yet their voices diverged in tone and form.

Osip Mandelstam also looms large. His cryptic, allusive poetry made him a target of Stalin’s wrath. Chukovskaya, recognizing the greatness of Mandelstam’s work, became one of his earliest defenders. Her memoir The Deserted House recalls her conversations with Akhmatova and her commitment to preserving Mandelstam’s legacy, even at great personal risk.

While Chukovskaya may not have produced a large body of verse, her defense of poetry—of the right to write freely and truthfully—makes her a central figure in Russian poetry’s modern history.

Themes and Language in Chukovskaya’s Poetry

The themes of Chukovskaya’s poetry are closely tied to her personal experiences. The trauma of Stalin’s purges, the grief of losing loved ones, and the moral imperative to remember inform nearly every line she wrote. Her poetry is quiet, almost meditative, but never detached. It is infused with empathy and conscience.

Her language is simple, direct, and clear. She avoids ornamentation and rhetorical flourish. This stylistic choice reflects her commitment to truth. For Chukovskaya, poetry was not an escape but a form of witness. It had to be accessible, honest, and rooted in reality.

Consider a brief excerpt (translated into English):

“Not to forget / Not to forgive / Not to bow / Not to explain…”

These lines, stark and declarative, carry the weight of memory and moral clarity. They speak not just to personal grief but to collective responsibility. In this way, Chukovskaya’s poetry aligns with the ethical tradition of Russian literature—from Dostoevsky to Solzhenitsyn.

Legacy and Influence

Chukovskaya’s legacy is multifaceted. As a poet, she belongs to the quiet tradition of resistance through remembrance. As a writer, she preserved the memory of others when it was dangerous to do so. As a friend and defender of the persecuted, she stood alongside giants.

In the post-Soviet era, her reputation has grown. Scholars of Russian poetry now recognize her as more than a memoirist or prose writer. Her poems, though few, have been included in anthologies of Russian poetry. Her voice, steady and principled, continues to resonate in a world still grappling with censorship, propaganda, and state violence.

It is important to note that Lydia Chukovskaya’s work bridges genres—poetry, prose, memoir, literary criticism—and in doing so, she embodies the broader struggle of 20th century Russian poets to survive and speak under repressive regimes. Her writings contribute to the moral archive of a century marked by devastation and endurance.

Conclusion

Lydia Chukovskaya stands among the most important figures in Russian literature of the 20th century. Though not primarily known as a poet, her poetic contributions, both in verse and in life, position her within the tradition of 20th century Russian poets who refused silence in the face of terror.

In comparing her to other Russian poets of her time—Akhmatova, Tsvetaeva, Mandelstam—we see a shared commitment to truth and artistic freedom, though expressed through very different styles and temperaments. Chukovskaya’s poetry, characterized by its clarity and restraint, provides a quiet but enduring counterpoint to the grand voices of her era.

Her life reminds us that Russian poetry in the 20th century was not only about beauty and form—it was also about courage, resistance, and the preservation of human dignity. In honoring Lydia Chukovskaya, we honor that legacy.