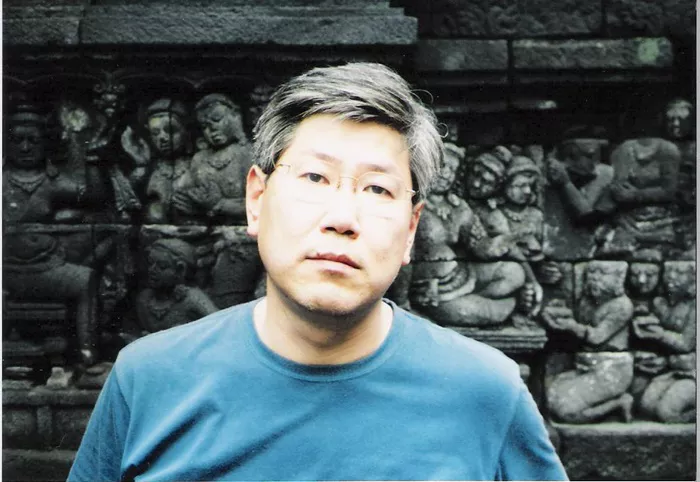

The development of Japanese poetry in the 21st century has seen a dynamic evolution, as traditional forms blend with modern perspectives. Among the significant voices contributing to this transformation is the Japanese poet Hisaki Matsuura, born in 1954. Matsuura’s work bridges past and present, offering a literary lens through which readers can view both the legacy and the reinvention of poetic expression in contemporary Japan. His contribution is notable not only for its thematic depth but also for its stylistic innovation. In a poetic era defined by both continuity and rupture, Matsuura stands out as a thinker and creator deeply engaged with the complexities of modern identity, language, and art.

Introduction to 21st Century Japanese Poets

The 21st century has witnessed a renewed interest in poetry among Japanese readers and writers. These poets operate in a world shaped by rapid technological change, globalization, and evolving cultural identities. While some have chosen to embrace traditional poetic forms such as haiku and tanka, others have moved toward free verse, hybrid styles, and even multimedia poetry. Within this landscape, a number of poets have emerged as central figures in redefining what Japanese poetry can mean in this new century.

Among these 21st century Japanese poets, there is a shared commitment to introspection and experimentation. Their works often examine the tension between individual and society, the fleeting nature of time, and the enduring question of what it means to be human. This group includes well-known names such as Shuntaro Tanikawa, Ryoichi Wago, and Hiromi Itō. Hisaki Matsuura, however, offers a unique voice that is both philosophical and poetic, scholarly and emotive.

Hisaki Matsuura: Life and Background

Although often classified as a contemporary writer, Hisaki Matsuura began his career in the latter part of the 20th century. Born in 1954 in Tokyo, he studied French literature at the University of Tokyo and later became a professor. This academic background has had a strong influence on his literary work. He is known not only as a poet but also as a novelist, critic, and translator. His multilingual expertise and deep engagement with Western philosophy have enriched his Japanese poetry, infusing it with intellectual rigor and cross-cultural resonance.

Matsuura’s work reflects a conscious engagement with European thought, particularly the works of Nietzsche, Baudelaire, and French symbolist poets. This global sensibility has allowed him to develop a poetic voice that is at once deeply Japanese and universally human.

Stylistic Characteristics of Matsuura’s Poetry

Hisaki Matsuura’s poetry is notable for its clarity, abstraction, and meditative tone. He often writes in free verse, avoiding the constraints of traditional Japanese forms. Yet his poetic language is deeply rooted in the aesthetics of Japanese culture, including the concepts of yūgen (mysterious profundity), mono no aware (sensitivity to ephemera), and wabi-sabi (austere beauty).

His poems explore themes such as time, death, silence, and the nature of being. Rather than focusing on personal narrative or external events, he tends to examine inner landscapes. His work invites readers to pause, reflect, and engage with poetry as a space for philosophical inquiry. This places him in contrast with some of his contemporaries who have leaned more toward political or autobiographical themes.

Matsuura’s style is minimalistic, often using short lines and sparse imagery. He uses metaphor not for ornamentation but as a tool for thought. The result is a body of work that feels intimate and intellectual, personal and metaphysical.

Major Works and Themes

Among Hisaki Matsuura’s most celebrated poetry collections is “Hikari no riron” (Theory of Light). In this work, Matsuura explores the relationship between light and perception, using light as a metaphor for consciousness, memory, and existence. The poems are dense with philosophical allusions yet remain accessible in their language.

Another important work is “Kaze no kioku” (Memory of the Wind), in which nature becomes a mirror for the poet’s internal world. Here, wind serves not only as a natural force but as a symbol for change, absence, and transience. These recurring motifs are common in Japanese poetry, yet Matsuura gives them new life through his philosophical treatment.

In “Kū to ketsugō” (Void and Union), the poet confronts themes of emptiness and connection. Drawing from both Buddhist concepts and Western existentialism, he reflects on the paradoxes of solitude and togetherness. This work highlights his capacity to synthesize disparate intellectual traditions into a cohesive poetic vision.

Comparison with Contemporary Japanese Poets

To better understand Matsuura’s place in modern Japanese poetry, it is helpful to compare his work with other 21st century Japanese poets. Shuntaro Tanikawa is perhaps the most famous living Japanese poet. His work is marked by emotional openness and accessibility. While Tanikawa often addresses themes of love, childhood, and everyday life, Matsuura tends to focus on abstract and philosophical concerns. Tanikawa’s poems are outward-looking and often infused with optimism, whereas Matsuura’s are introspective and meditative.

Hiromi Itō, another prominent figure, is known for her bold, confessional voice and feminist themes. Her poetry often explores the female body, sexuality, and motherhood. In contrast, Matsuura’s voice is more gender-neutral, less concerned with personal identity and more with existential inquiry.

Ryoichi Wago, a younger poet, gained fame for his poetry in response to the 2011 Fukushima disaster. His work is urgent, political, and deeply rooted in the specific context of contemporary Japan. Matsuura, by contrast, engages with timeless philosophical questions that transcend particular events.

These comparisons highlight the diversity of 21st century Japanese poets. While many contemporary poets are grounded in personal or political realities, Matsuura offers a poetic space for abstract reflection. His work complements that of his peers by providing a different mode of engagement with the world.

Philosophical Influences and Interdisciplinary Approach

Matsuura’s academic background plays a significant role in shaping his poetry. He has written extensively on philosophy, and his poetic voice reflects this intellectual heritage. He often cites philosophers such as Heidegger, Merleau-Ponty, and Deleuze. These influences are not merely decorative; they form the conceptual scaffolding of his poetic practice.

His interdisciplinary approach sets him apart from many Japanese poets. He does not see poetry as separate from other forms of thought. Instead, he treats it as a mode of philosophical investigation. His poems pose questions rather than offer answers. They reflect a Socratic method in verse, drawing the reader into a process of inquiry.

In this way, Matsuura’s work is similar to that of Western poets such as Wallace Stevens or Paul Celan, who also explored the boundaries between language, thought, and being. Yet his grounding in Japanese aesthetics gives his work a distinctive character.

Language and Translation

Although Hisaki Matsuura writes primarily in Japanese, his fluency in French and deep engagement with Western literature have made him an important figure in the translation of ideas across languages. Some of his work has been translated into English, though he remains less known in the Anglophone world than he deserves.

The challenge of translating Matsuura lies not only in capturing the meaning of his words but in conveying the philosophical and aesthetic dimensions of his language. His poems often rely on subtle shifts in tone, rhythm, and metaphor. These qualities are rooted in the nuances of the Japanese language and are difficult to reproduce.

Nevertheless, translation plays a vital role in extending the reach of Japanese poetry. Matsuura’s work, when shared beyond Japan, contributes to global conversations about the nature of poetry and the role of the poet in modern society.

The Role of the Poet in 21st Century Japan

Hisaki Matsuura offers a model of the poet as philosopher. In an age dominated by technology, speed, and distraction, his work insists on slowness, silence, and reflection. This makes his poetry both timely and timeless.

21st century Japanese poets are tasked with addressing a rapidly changing society. Economic uncertainty, environmental crises, and cultural fragmentation pose new challenges for literary expression. In this context, Matsuura’s poetry provides a space for stillness and contemplation. He does not propose solutions but offers a space in which questions can be asked and meanings can be explored. His work suggests that poetry remains a vital form of human expression, even—or especially—in uncertain times.

Legacy and Influence

Although not as widely read as some of his contemporaries, Matsuura’s influence on younger poets and scholars is significant. His integration of philosophical thought with poetic form has inspired a new generation to see poetry not just as emotional expression but as intellectual inquiry.

He has also contributed to literary criticism and education in Japan, further shaping the discourse around poetry. His lectures, essays, and translations have helped to expand the boundaries of Japanese poetic thought.

As 21st century Japanese poetry continues to evolve, Hisaki Matsuura’s work will likely remain a point of reference. His contribution lies not only in his own writing but in his broader role as a thinker, teacher, and bridge between traditions.

Conclusion

The Japanese poet Hisaki Matsuura stands as a singular voice among 21st century Japanese poets. His poetry reflects a deep commitment to both aesthetic beauty and philosophical inquiry. In an age where many poets turn outward toward society and politics, Matsuura turns inward toward being and thought. His minimalist style, intellectual rigor, and cross-cultural sensibility distinguish him as one of the most important poetic thinkers of his generation.

As we consider the future of Japanese poetry, Matsuura’s work reminds us of the enduring power of language to explore the unknown, to question the familiar, and to connect the individual mind with the vast world of ideas. In a time of noise, his poetry offers quiet. In a world of answers, he returns us to the wisdom of questions.