Among the most intriguing figures in 20th century Italian poetry is Gesualdo Bufalino, a writer whose literary career began late but left a lasting mark. Known primarily for his prose, Bufalino also contributed significantly to the lyrical tradition of Italian poetry. Born in 1920 in Comiso, Sicily, he lived through the tumultuous decades of Fascism, World War II, and Italy’s postwar transformation. His poetic work, although often overshadowed by his novels, carries the richness of language, the tension between life and death, and the existential themes that define many 20th century Italian poets.

This article explores Bufalino’s poetic voice, its place within the broader canon of Italian poetry, and its relation to other contemporaries like Eugenio Montale, Salvatore Quasimodo, and Pier Paolo Pasolini. Through this examination, we gain a deeper understanding of the evolution of poetic expression in Italy during a century marked by crisis, reconstruction, and reflection.

The Late Bloom of a Poetic Voice

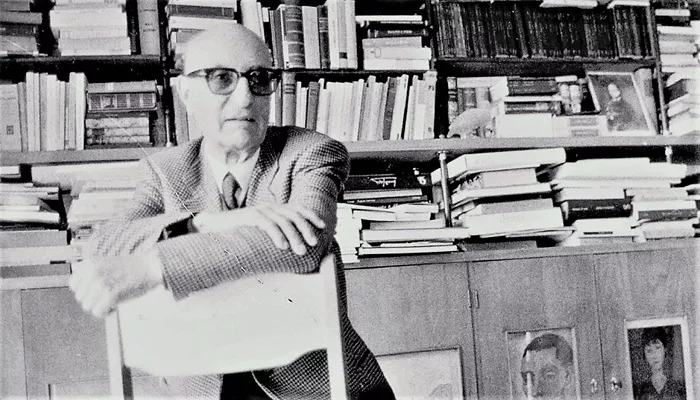

Gesualdo Bufalino did not publish his first work until the age of sixty-one. His debut novel, Diceria dell’untore (The Plague-Sower’s Tale), received immediate acclaim and opened the door for further literary production, including poetry. Despite this late start, his background as a literature teacher and translator had refined his sensitivity to language and form.

His poetry, collected in volumes like L’amaro miele (The Bitter Honey), often feels like prose distilled to its essence. It is meditative, elegiac, and linguistically rich. The themes Bufalino grapples with—death, memory, silence, and identity—are central to the landscape of Italian poetry in the 20th century. In particular, his Sicilian identity adds a regional texture to his work, linking him to other Sicilian poets such as Quasimodo and Leonardo Sciascia, though Bufalino’s tone is more introspective and less political.

In this, Bufalino represents a thread of continuity within Italian poetic tradition—one where regionalism, history, and personal memory converge.

Italian Poetry in the 20th Century: A Landscape of Change

The 20th century was a transformative period for Italian poetry. It began with the echoes of Decadentism and the residue of 19th-century Romanticism. Poets like Gabriele D’Annunzio defined the early decades with ornate language and nationalistic themes. However, the two world wars, the rise of Fascism, and the existential crises of modernity shifted poetic expression dramatically.

In the postwar period, Italian poetry turned inward. It became more experimental and more fragmented, reflecting a world that had lost its certainties. Gesualdo Bufalino’s poetry is firmly situated in this postwar poetic evolution. His works belong to a generation that bore witness to destruction but sought to reconstruct meaning through the act of writing.

Bufalino’s language, rich in literary allusion and philosophical depth, echoes the hermetic tradition seen in Eugenio Montale’s work. Yet while Montale’s poetry often conveys a stark, dry tone, Bufalino’s has a warmer, though equally sorrowful, flavor. His verses are filled with historical and literary references, offering a layered reading experience for those familiar with the broader Western canon.

The Poetic Themes of Bufalino

Central to Bufalino’s poetry is the theme of death. Unlike many of his contemporaries who approached death through political or existential lenses, Bufalino gives it an almost sensual quality. In L’amaro miele, the imagery of decay is beautiful, almost baroque. He writes of bones and silence, of lovers turned to dust, with a language that evokes both horror and tenderness.

This unique treatment of mortality distinguishes him from other 20th century Italian poets. While Quasimodo, also a Sicilian, wrote of war and exile in a political and moral tone, Bufalino writes of internal exile—the exile from youth, from beauty, from the living. His poetry is a meditation on time, a battle against oblivion.

Another persistent theme in his work is the idea of the double. Bufalino was fascinated by mirrors, masks, and identities. This is not uncommon in Italian literature—Pirandello, for instance, explored similar themes—but Bufalino gives the motif a personal twist. His poetic self often speaks in riddles and reversals, creating a labyrinth of meanings.

A Comparison With Contemporaries

To understand Bufalino’s place among 20th century Italian poets, it is helpful to compare his work with that of several key figures:

Eugenio Montale: Montale’s Ossi di seppia (Cuttlefish Bones) is a cornerstone of modern Italian poetry. His verses are terse, elliptical, and filled with bleak imagery. Montale’s “hermeticism” seeks to convey meaning through obliqueness. Bufalino’s work shares this density of language but is more lyrical. Where Montale closes doors, Bufalino leaves them ajar, inviting readers into a poetic puzzle.

Salvatore Quasimodo: Also a Nobel laureate, Quasimodo’s early work was similarly hermetic but evolved into a more social and political engagement. He was deeply affected by the war and used poetry as a tool of moral reflection. Bufalino, by contrast, retreats from the political. His poetry is private, philosophical, and infused with classical references. Yet both share a love for musical language and Mediterranean imagery.

Pier Paolo Pasolini: Pasolini’s poetry, raw and polemical, stood at the intersection of politics, religion, and sexuality. His Roman dialect poems broke with traditional forms and addressed the real, physical world. Bufalino’s poetry is more abstract, less concerned with the flesh of society and more with its shadows. Still, both poets interrogate identity and loss, although through very different lenses.

Through these comparisons, Bufalino’s uniqueness becomes clear. While many of his contemporaries moved outward, toward society and its crises, Bufalino remained inward-looking. His poetry resembles a monastery cell—a space of contemplation and silence.

The Italian Poet as Witness

Despite his reclusive style, Bufalino can still be seen as a witness of his time. His memory of war, particularly his time in a German POW camp, informed much of his writing. Unlike Primo Levi or Italo Calvino, he does not chronicle events directly. Instead, he sublimates trauma into metaphor. His poetry transforms historical memory into personal myth.

In doing so, Bufalino contributes to the role of the Italian poet as a keeper of collective conscience. This tradition, from Dante to Leopardi to Montale, sees poetry not just as art but as moral testimony. Though Bufalino’s voice is soft, it carries the gravity of someone who has known both beauty and despair.

The Musicality of Language

Bufalino was a master of language. His work demonstrates an extraordinary sensitivity to rhythm, tone, and wordplay. In L’amaro miele, each poem reads like a miniature sonata—delicate, precise, and haunting. This musical quality links him to the classical tradition of Italian poetry, which values form as much as content.

Yet Bufalino also experiments with modern techniques. His syntax is at times fragmented; he plays with enjambment, ellipses, and neologisms. These devices connect him with the avant-garde movements of his time, even if he never fully embraced modernist aesthetics.

The result is a hybrid voice: classical yet modern, lyrical yet intellectual. Bufalino proves that even in the age of prose dominance, the Italian poet can still craft verses of lasting power.

Legacy and Influence

Gesualdo Bufalino died in 1996, leaving behind a relatively small but powerful body of work. His poetry, though not as widely studied as his prose, is gaining recognition among scholars and readers. It reflects a quieter current in 20th century Italian poetry—one that values introspection over innovation, clarity over disruption.

Today, younger Italian poets often cite Bufalino as an influence, particularly for his fusion of philosophical depth with lyrical beauty. His Sicilian background also continues to inspire writers from the South of Italy, who see in him a model for how to turn regional identity into universal expression.

His poetic legacy stands as a testament to the enduring richness of Italian poetry. In an age dominated by digital media and ephemeral texts, Bufalino’s carefully crafted verses remind us of the power of language to illuminate the human condition.

Conclusion

In the tapestry of 20th century Italian poets, Gesualdo Bufalino occupies a unique space. He is a poet of silence and shadows, of memory and mortality. Though he arrived late on the literary scene, his contribution to Italian poetry is both profound and enduring.

Through careful comparison with contemporaries such as Montale, Quasimodo, and Pasolini, we see that Bufalino’s poetic vision is both singular and connected. He draws from the deep wells of Italian literary tradition while offering a voice that is unmistakably his own.

In celebrating Gesualdo Bufalino, we celebrate the Italian poet as philosopher, artist, and witness. His work invites us to listen carefully—not just to words, but to the silences between them. And in those silences, we find the echo of a century, and perhaps, the whisper of eternity.