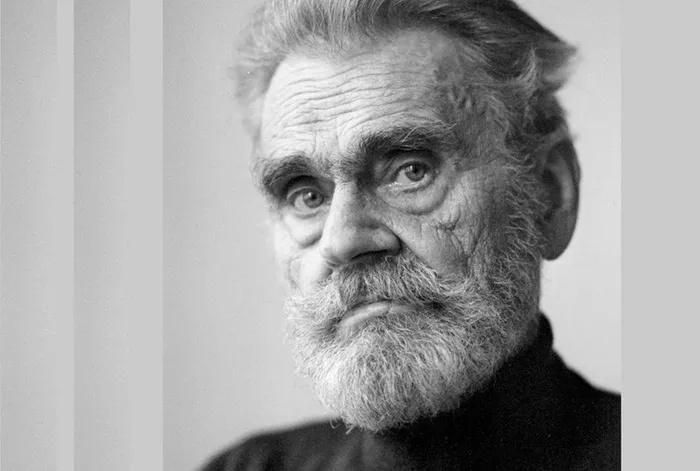

Hans Carl Artmann, a central figure in postwar European literature, stands out as one of the most inventive and playful minds in 20th Century German poetry. Born in Vienna in 1921 and active through much of the postwar era until his death in 2000, Artmann’s poetic vision defied conventional boundaries of language, genre, and identity. Although Austrian by birth, Artmann wrote in both Standard German and dialect, placing him firmly within the broader tradition of German poets. His contribution to German poetry is both experimental and linguistically rich, challenging readers with humor, depth, and political resonance.

In a century marked by war, reconstruction, and rapid shifts in art and ideology, Artmann emerged not just as a 20th Century German poet, but as a poet of European pluralism. His work intersects with many contemporaries—Ingeborg Bachmann, Paul Celan, and Günter Eich—but also stands apart for its deep engagement with language play and its commitment to anarchic freedom.

This article explores Artmann’s life, poetic innovations, relationship with language, and his place among other 20th Century German poets, while offering a broader understanding of how his works reflect and reshape German poetry in the postwar era.

Hans Carl Artmann

Hans Carl Artmann was born on June 12, 1921, in Vienna, Austria. From a young age, he was exposed to a polyphonic world of dialects, fairy tales, and literary traditions. His father, a shoe-maker, had nationalist sentiments, while Artmann gravitated toward internationalism, surrealism, and linguistic diversity. These early tensions between identity, nationalism, and language would inform much of his work.

Artmann’s multilingual environment included Viennese dialect, Standard German, and occasional exposure to Slavic languages. His fascination with words extended beyond content to sound and structure. This sensitivity would become a defining characteristic of his poetry.

While many 20th Century German poets embraced lyric introspection or political commitment, Artmann gravitated toward a radical engagement with language itself. He often manipulated language for its texture, rhythm, and humor rather than for narrative coherence or traditional lyricism. This focus on sound aligned him with avant-garde traditions like Dadaism and Surrealism, as well as with earlier figures such as Christian Morgenstern and Hugo Ball.

The Founding of the Wiener Gruppe

One of Artmann’s major contributions to 20th Century German poetry was the founding of the Wiener Gruppe (Vienna Group) in the 1950s. Alongside other experimental artists and poets like H. C. Artmann (himself), Friedrich Achleitner, Konrad Bayer, Gerhard Rühm, and Oswald Wiener, this movement challenged postwar literary norms.

The Wiener Gruppe was radical in both aesthetics and politics. They drew inspiration from Dada, Surrealism, and linguistic philosophy. Artmann, as its most visible public figure, played a key role in promoting experimental literature as a means of cultural and political resistance. His anarchic humor and anti-authoritarian stance resonated with postwar disillusionment.

In contrast to contemporaries like Paul Celan, whose dense, tragic poems bore the weight of Holocaust memory, or Ingeborg Bachmann, whose work interrogated trauma and subjectivity, Artmann focused on linguistic liberation and parody. His poetic project was not to restore meaning, but to explode and multiply it.

Language Play and Dialect Poetry

One of Artmann’s most famous contributions to German poetry is his use of dialect, especially in his early work med ana schwoazzn dintn (1958). This title, written in Viennese dialect, translates roughly as “with a black ink.” The book was revolutionary in its use of a regional German dialect for serious, ironic, and absurd poetic expression.

Dialect poetry in 20th Century German poetry was rare and often marginalized. Artmann elevated it, giving it dignity and artistic power. He challenged the notion that high poetry must be written in Hochdeutsch (Standard German). His dialect poems were filled with grotesque imagery, black humor, and fairy-tale absurdity, subverting traditional poetic expectations.

Whereas poets like Gottfried Benn or Bertolt Brecht used German to evoke philosophical or political engagement, Artmann used dialect to dislocate the reader, forcing them to confront the instability of meaning itself.

Artmann’s dialect poems are often compared to the nonsense verse of Lewis Carroll or the linguistic experiments of James Joyce. Like Joyce’s Finnegans Wake, Artmann’s poems revel in the musicality of language. Yet Artmann maintains a distinctly Germanic flavor—dark, ironic, and subversively humorous.

Surrealism and Internationalism

Another hallmark of Artmann’s poetry is its engagement with Surrealism. After spending time in Paris, Sweden, and later Berlin, Artmann was deeply influenced by French Surrealists such as André Breton and Paul Éluard.

This is evident in his dreamlike imagery, juxtapositions, and anti-rational tone.

Artmann’s internationalism distinguished him from many other 20th Century German poets, especially those working within postwar national frameworks. His poetry draws from Celtic myth, Nordic folklore, and Mediterranean surrealism. This wide cultural net allowed him to escape nationalistic confines and propose a Europe united by linguistic and poetic play.

In contrast, fellow German poets like Nelly Sachs or Günter Eich often worked within national or moral frameworks to confront the horrors of the past. Artmann, by contrast, floated outside of national narratives, delighting in their collapse.

His translations also reflect this openness. Artmann translated works from French, Swedish, and Old Icelandic, demonstrating his profound respect for cross-cultural dialogue.

A Poetics of Anarchy

Artmann’s literary worldview was deeply anarchic. He distrusted authority, dogma, and systems—whether political or literary. This outlook infused his poetry with a spirit of rebellion. Even when writing about death, decay, or social dysfunction, he used humor and irony to resist solemnity.

His work has been compared to that of Christian Morgenstern, who also wrote humorous, absurd verse in German. But where Morgenstern was whimsical, Artmann was often dark and politically charged. His black humor, grotesque settings, and surreal characters critique bourgeois norms and expose the absurdities of modern life.

Artmann’s anarchism wasn’t nihilistic. He believed in the liberating power of art and imagination. Like fellow 20th Century German poet Ernst Jandl, he explored how sound and language could resist authoritarian control. In this sense, both poets share affinities with the sound poetry of the Dadaists and the experimental poetics of concrete poetry.

Artmann and the Poetic Tradition

Despite his radicalism, Artmann saw himself as part of a long poetic tradition. He admired medieval verse, baroque literature, and early modern poetry. His works often parody traditional forms while paying homage to them.

For example, his 1972 volume dracula dracula is both a satirical horror collection and a tribute to Gothic storytelling. Artmann was skilled at mixing registers—combining medieval diction with modern slang, or epic tropes with suburban absurdity.

In this blending of past and present, Artmann shares a kinship with other 20th Century German poets such as Peter Rühmkorf and Hans Magnus Enzensberger, who also sought to renew tradition through irony and experimentation.

Legacy and Influence

Hans Carl Artmann’s legacy is profound. He expanded the range of German poetry, introducing play, parody, and dialect into a literary scene still shaped by war trauma and existential seriousness. His work influenced generations of Austrian and German writers, especially those interested in language experimentation.

In 1997, Artmann was awarded the Georg Büchner Prize, the highest honor for German-language literature. The award acknowledged not just his poetic achievements, but his role in revitalizing postwar German poetry through humor, innovation, and linguistic courage.

Unlike some of his contemporaries, Artmann did not found a school or strict aesthetic movement. Instead, he offered a model of poetic freedom. He showed that poetry could be joyful, multilingual, and anarchic without losing intellectual depth.

Comparisons with Other 20th Century German Poets

To understand Artmann’s unique place in 20th Century German poetry, it is helpful to compare him to other major figures of the time:

Paul Celan: Celan’s poetry is dense, tragic, and haunted by the Holocaust. His compressed, broken syntax seeks a truth beyond words. Artmann, by contrast, explodes meaning through sound and parody. Where Celan turns inward, Artmann plays outward.

Ingeborg Bachmann: Bachmann’s lyrical introspection and feminist critique contrast with Artmann’s theatrical surrealism. Both are political, but Artmann’s anarchism is playful and subversive, while Bachmann’s is melancholic and ethical.

Günter Eich: A poet of silence and moral responsibility, Eich represents the postwar introspective voice. Artmann counters this with noise, laughter, and chaos.

Ernst Jandl: Jandl and Artmann share an interest in sound poetry and linguistic experimentation. Jandl’s minimalism and phonetic play, however, often carry more conceptual rigor, whereas Artmann indulges in excess and narrative surprise.

In this context, Artmann appears not as an outsider but as a counterforce within the German poetry tradition—a necessary jester in a court of solemn witnesses.

Conclusion

Hans Carl Artmann is a crucial figure in the history of 20th Century German poetry. His poetic work, spanning dialect verse, surrealism, anarchic prose, and sound experiments, defies easy classification. He was a true linguistic alchemist, blending words into magical, musical, and monstros.

As a German poet, Artmann challenged literary tradition without abandoning it. He embraced the grotesque, the comic, the absurd, and the revolutionary. His work reminds us that poetry is not just a mirror of suffering or a tool for truth, but also a playground of freedom.

In a century torn by war, ideology, and division, Hans Carl Artmann carved out a space of joyful resistance. His poetry continues to inspire readers and writers to see language not as a prison of meaning, but as a field of infinite possibility. In doing so, he redefined what it meant to be a 20th Century German poet and expanded the horizons of German poetry for generations to come.