In the rich and diverse landscape of 19th century French poetry, a few names dominate literary discussions—Baudelaire, Verlaine, Mallarmé, and Rimbaud. However, the period was also shaped by lesser-known but equally innovative figures. One of these is Charles Cros, a unique and visionary poet who stood at the intersection of poetry, science, and early modernism. Charles Cros was not only a 19th Century French poet but also an inventor and essayist, whose contributions to French poetry reflect both imaginative daring and intellectual curiosity. Though overshadowed by more prominent contemporaries, his work embodies key elements of Symbolism and anticipates the surrealist movements of the 20th century.

This article explores Charles Cros as a representative 19th Century French poet, analyzing his life, literary style, thematic concerns, and influence. Comparisons with other French poets of the time help situate Cros within the broader context of French poetry. His marginalization from mainstream literary canon also invites reflection on how history selects and preserves literary figures.

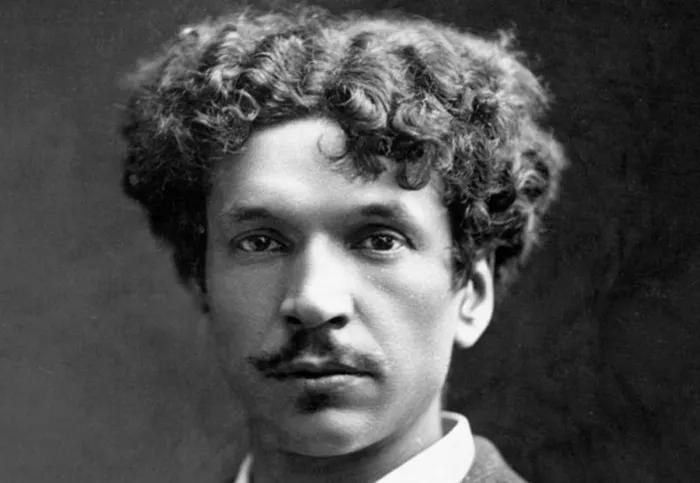

Charles Cros

Charles Cros was born on October 1, 1842, in Fabrezan, a commune in southern France. From an early age, he displayed diverse intellectual interests, including language, science, and music. He moved to Paris in his youth, where he pursued medical studies before turning his attention more fully to poetry and invention. Paris in the mid-19th century was a crucible of artistic and scientific creativity, and Cros found himself immersed in this energetic milieu.

Unlike many other French poets of his time, Cros was not part of a privileged class. He lived a bohemian lifestyle, often struggling financially, and relied on the support of fellow writers and friends. Despite this, he was active in Parisian literary circles and was associated with the Hydropathes, a group of artists and writers dedicated to art for art’s sake. His friendships with Paul Verlaine and Arthur Rimbaud also shaped his poetic orientation, even as his work remained distinct in tone and approach.

In addition to being a French poet, Cros was a pioneering inventor. He theorized the process of color photography and even proposed an early version of the phonograph. These pursuits demonstrate his commitment to bridging art and science, a theme that also runs through his poetic works.

Charles Cros and the Spirit of 19th Century French Poetry

To understand Cros as a 19th Century French poet, it is essential to situate him within the literary movements of his time. The century witnessed a shift from Romanticism to Symbolism, with Parnassianism serving as a transitional phase. Each movement had distinctive features:

Romanticism emphasized emotion, individualism, and nature.

Parnassianism focused on form, clarity, and classical themes.

Symbolism explored the mystical, the irrational, and the musical qualities of language.

Charles Cros did not belong strictly to any of these schools. However, he absorbed and responded to each. His poetry displays romantic sentiment, Parnassian technique, and Symbolist imagination. This hybridity made his work difficult to classify, contributing to his marginal status in the canon of French poetry.

Relationship with the Parnassians

Cros was sometimes grouped with the Parnassians, especially because of his interest in formal precision and mythological subjects. Like Théodore de Banville and Leconte de Lisle, he valued metrical discipline. However, unlike these poets, Cros infused his work with irony and playfulness. He was less concerned with timeless beauty and more interested in the intersection of humor and philosophical depth.

Foreshadowing Symbolism

More than any other movement, Symbolism resonates in Cros’s poetry. His work often evokes dreamlike visions and metaphysical speculation. This places him in proximity to poets like Stéphane Mallarmé and Paul Verlaine. Yet Cros retained a more tangible and sometimes comedic tone. Where Mallarmé’s verse could verge on the abstract, Cros remained grounded in material imagery and everyday observation.

Major Themes in Cros’s Poetry

Death and the Afterlife

One of the most compelling themes in Cros’s poetry is death. Unlike the solemn meditations of Romantic poets or the idealizations of Parnassians, Cros approached death with both reverence and absurdity. His famous poem “Le Coffret de santal” (“The Sandalwood Box”) exemplifies this attitude. It combines the delicate mood of loss with a sensory-rich description of a loved one’s keepsake.

Love and Eroticism

Love in Cros’s work often blends sensuality and irony. He was fascinated by the fleeting nature of beauty and the contradictions of desire. Poems like “Le Hareng saur” (“The Smoked Herring”) show how he used humor to deflate romantic clichés. At the same time, his poetry includes heartfelt evocations of longing and tenderness, making his treatment of love both multifaceted and human.

Science and the Imagination

Cros’s dual identity as a poet and inventor appears in his use of scientific metaphors and concepts. He often imagined fantastical machines or cosmic voyages. These elements connect him to later French poetry movements such as Surrealism and Futurism. For Cros, science was not merely a field of empirical inquiry; it was a portal to poetic vision.

Satire and Parody

Many of Cros’s poems are satirical. He mocked the pretensions of bourgeois society, the rigidity of formal education, and even the literary world itself. This satirical edge links him with Rimbaud’s rebellious energy, although Cros’s tone was generally less incendiary and more whimsical.

Selected Works of Charles Cros

Cros’s most important poetic collection is “Le Coffret de santal” (1873), which gathers many of his best-known poems. The title alludes to the preciousness of memory and the exotic allure of distant lands, both recurring motifs in his poetry. Other notable poems include:

“Le Hareng saur” – A humorous monologue about a smoked herring, layered with social commentary.

“Le Fleuve” – A lyrical reflection on the passage of time, blending natural imagery with philosophical insight.

“L’Orgie parisienne” – A grotesque portrayal of urban excess and decadence.

These works reveal Cros’s capacity to shift between tones—comic, lyrical, meditative—without losing coherence. His mastery of form and sound supports this versatility, as does his vivid imagery.

Charles Cros and His Contemporaries

To appreciate Cros’s place in 19th century French poetry, it is helpful to compare him with better-known contemporaries.

Charles Baudelaire

Baudelaire, often called the father of modern French poetry, emphasized urban alienation, eroticism, and the aesthetics of decay. Like Baudelaire, Cros found inspiration in the city and in sensory experience. However, Baudelaire’s tone was often tragic and philosophical, while Cros balanced introspection with satire.

Paul Verlaine

Verlaine, known for his musicality and Symbolist leanings, was a friend of Cros. Both poets were drawn to mood and suggestion rather than narrative clarity. Yet Verlaine focused more on emotional nuance and spiritual ambiguity, while Cros remained interested in external realities and scientific metaphors.

Arthur Rimbaud

Rimbaud and Cros shared an iconoclastic spirit. Both questioned poetic norms and experimented with language. Rimbaud’s influence is more visible in 20th-century avant-garde movements, but Cros also anticipated these trends. Where Rimbaud’s work is intense and revolutionary, Cros’s poetry often appears more playful, yet no less inventive.

Cros as Precursor to Modernism

Though Cros died in 1888, his poetry remained relevant into the 20th century. Surrealists such as André Breton admired his capacity for dreamlike imagery and conceptual daring. His exploration of consciousness, perception, and artificiality places him in the lineage of modernist experimentation.

His poetic technique, which often included abrupt shifts in tone, playful logic, and invented lexicons, aligns with modernist aesthetics. These features also distinguish him from more traditional 19th Century French poets, who adhered more strictly to classical forms.

The Inventor as Poet

Cros’s contributions to photography and sound recording illustrate his belief in the interconnection of disciplines. He theorized a process for color photography years before the Lumière brothers succeeded in its realization. Similarly, he developed a version of the phonograph, which he called the “paleophone,” around the same time as Thomas Edison.

These inventions were not just technical feats; they represented new ways of capturing and preserving human experience. This is also the aim of poetry. In this way, Cros’s identity as a French poet and as a scientist was not contradictory, but complementary.

Legacy and Rediscovery

Charles Cros’s reputation suffered after his death. Unlike Mallarmé, whose aesthetic theories inspired generations of poets, or Rimbaud, whose life became mythologized, Cros faded from literary memory. Yet there has been renewed interest in his work since the mid-20th century. The Académie Charles Cros, founded in 1947 to promote audio recording and poetic arts, was named in his honor.

Cros’s ability to merge humor and depth, his openness to interdisciplinary thinking, and his experimental poetics now appear prescient. As scholars re-evaluate the canon of 19th century French poetry, Cros’s position becomes more secure.

Conclusion

Charles Cros was a 19th Century French poet who defied easy categorization. His work synthesizes formal discipline with imaginative freedom. He explored themes such as death, love, science, and satire, using language that is at once musical and conceptual. Although he was overshadowed by poets like Baudelaire, Verlaine, and Rimbaud, Cros made unique contributions to French poetry.

In bridging thlds of poetry and invention, Cros anticipated many aspects of modernist and postmodernist thought. He belongs to the lineage of French poets who expanded the boundaries of poetic language and imagination. Today, as we rediscover neglected voices, Cros stands out as a pioneer—playful, profound, and prophetic.

The legacy of Charles Cros invites us to consider how innovation, in both form and content, shapes the trajectory of literature. He remains a remarkable figure in the history of 19th century French poetry—one who reminds us that poetry is not only about beauty or emotion but also about curiosity, experimentation, and the joy of language.