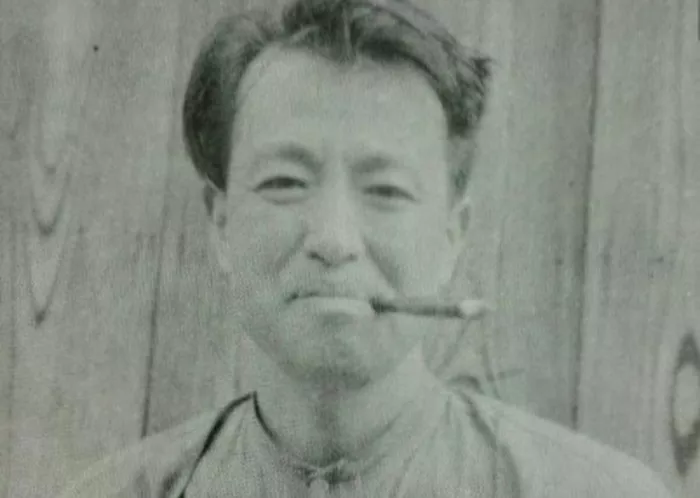

The landscape of Japanese poetry in the 20th century is marked by a vibrant transformation, a fusion of tradition and modernity that gave rise to voices both subtle and profound. Among these voices, the contributions of Tōzaburō Ono stand out for their nuanced engagement with both classical forms and new poetic sensibilities. Born in 1903, Ono’s work exemplifies the complexities and innovations characteristic of 20th century Japanese poets. To appreciate his legacy fully, it is important to place him within the broader context of Japanese poetry during this dynamic era.

Historical Context of 20th Century Japanese Poetry

The 20th century in Japan was a time of significant social, political, and cultural change. The nation experienced rapid modernization, the effects of Western influence, two world wars, and a post-war period of rebuilding. Japanese poetry mirrored these shifts. Poets explored new themes, experimented with forms, and redefined the role of poetry in society.

Japanese poetry, traditionally dominated by forms such as waka and haiku, began to diversify during this period. The traditional poetic modes continued to have influence, but poets increasingly adopted free verse and other Western-inspired forms. This diversification allowed poets to express the complexities of contemporary life, ranging from personal introspection to societal critique.

Tōzaburō Ono: Life and Poetic Contributions

Though not always the most widely known among the pantheon of 20th century Japanese poets, Tōzaburō Ono played a critical role in this poetic evolution. Born in 1903, Ono’s career spanned much of the century’s major events, and his poetry reflects a deep engagement with both traditional Japanese aesthetics and the modern world.

Ono was known for his lyrical sensitivity and philosophical depth. His poetry often explored themes of nature, impermanence, and the human condition—common themes in Japanese poetry—but he approached them with a modern consciousness shaped by the turbulent times he lived through. His work bridges the old and new, embodying the tension and harmony between classical Japanese poetic heritage and 20th century innovations.

Poetic Style and Themes

The style of Tōzaburō Ono’s poetry is characterized by a delicate balance of simplicity and complexity. Like many Japanese poets, Ono embraced minimalism, but his work is marked by subtle layers of meaning. This approach resonates with the traditional Japanese aesthetic concept of wabi-sabi, which finds beauty in imperfection and transience.

In Ono’s poems, nature is not merely a backdrop but a living presence that reflects human emotions and philosophical ideas. He often used natural imagery—such as falling leaves, flowing water, and seasonal changes—to evoke the fleeting nature of life. This use of imagery connects him to earlier generations of Japanese poets, including those of the Edo period, while also reflecting the existential questions prominent in 20th century literature.

Unlike some contemporaries who embraced overt political or social themes, Ono’s poetry tends to be more introspective. However, his subtle reflections on impermanence and change indirectly respond to the rapid modernization and upheavals experienced by Japan during his lifetime.

Comparison with Contemporary 20th Century Japanese Poets

To better understand Ono’s place in 20th century Japanese poetry, it is helpful to compare his work with other notable poets of the period, such as Shūji Terayama, Hagiwara Sakutarō, and Ishikawa Takuboku.

Hagiwara Sakutarō (1886–1942) is often credited as the father of modern free verse in Japanese poetry. His work introduced new psychological depth and raw emotional expression. Compared to Hagiwara’s sometimes intense and turbulent style, Ono’s poetry is more subdued and meditative.

Ishikawa Takuboku (1886–1912) was known for his tanka poems that blended personal emotion with social commentary. Takuboku’s sharp, often biting tone contrasts with Ono’s quieter, more reflective voice. However, both poets share an interest in exploring the inner emotional landscape.

Shūji Terayama (1935–1983), though younger and working in a more avant-garde mode, pushed the boundaries of poetic form and performance. Ono’s poetry remains more traditional in form, yet both poets show a commitment to exploring the limits of expression.

In this context, Ono’s work can be seen as a bridge between tradition and innovation. He maintained a respectful engagement with classical forms while incorporating the philosophical concerns and stylistic openness that characterized much of 20th century Japanese poetry.

The Role of Tradition in Ono’s Poetry

A defining feature of many 20th century Japanese poets was their relationship with tradition. Some sought to break free entirely from classical forms, while others reinterpreted tradition in light of modern experience.

Tōzaburō Ono’s poetry is firmly rooted in traditional Japanese poetic sensibility. He often composed in classical forms such as tanka and haiku, yet he infused them with contemporary themes and a modern awareness of existential impermanence. This blending is significant, as it reflects a broader cultural effort to reconcile Japan’s past with its rapidly changing present.

Ono’s work exhibits the traditional Japanese value of mono no aware — the gentle sadness or wistfulness at the passing of things. His poems frequently evoke this sentiment through delicate imagery and restrained emotion. This subtlety distinguishes his poetry from more dramatic or overtly political work by some of his contemporaries.

Contribution to Japanese Poetry and Legacy

The legacy of Tōzaburō Ono lies in his ability to sustain a dialogue between past and present. His poetry serves as a quiet but powerful reminder of the enduring relevance of classical poetic forms and themes in modern Japan.

Ono’s work also contributes to a larger understanding of 20th century Japanese poetry as a field marked by diversity and complexity. While some poets focused on radical innovation or social critique, Ono’s introspective and lyrical voice offers an alternative path—one that emphasizes reflection, subtlety, and aesthetic continuity.

His poems have influenced subsequent generations of poets who seek to explore traditional themes with a modern sensibility. By preserving classical forms while engaging deeply with contemporary experience, Ono helped maintain the vitality of Japanese poetry throughout the 20th century.

Broader Trends Among 20th Century Japanese Poets

The career of Tōzaburō Ono parallels broader trends among Japanese poets during the 20th century. The century saw an expansion in poetic forms—from traditional waka and haiku to free verse and prose poetry. Poets grappled with the tension between maintaining cultural heritage and embracing modernization.

This era also saw a growing international awareness, with many poets influenced by Western literature and philosophy. Yet, despite these influences, many Japanese poets, including Ono, retained a unique voice grounded in native aesthetics and language.

20th century Japanese poets also increasingly addressed themes of identity, alienation, and the impact of war and social change. While Ono’s poetry is less explicitly political, his work’s meditation on impermanence resonates with the experiences of loss and change common in the century’s literature.

Conclusion

Tōzaburō Ono represents an important strand of 20th century Japanese poetry. Born in 1903, he lived through a century of extraordinary change, yet his poetry remained deeply connected to the classical traditions of Japanese verse. His lyrical, contemplative style, focus on nature and impermanence, and subtle philosophical undertones place him among the notable Japanese poets who helped shape the literary culture of modern Japan.

His work offers a valuable counterpoint to more radical or overtly modernist poets of the same period. Through Ono, we see how Japanese poetry in the 20th century was not simply a story of rupture but also one of continuity, adaptation, and quiet resilience.

For readers and scholars of Japanese poetry, exploring Ono’s work enriches our understanding of the era’s poetic diversity and the enduring power of tradition within modern artistic expression. His legacy reminds us that in Japanese poetry, as in life, beauty often lies in the balance between change and continuity.