Philippe Soupault was a major figure in the early 20th century literary avant-garde. As a 20th Century French poet, his work spanned multiple movements, most notably Dadaism and Surrealism. His contribution to French poetry is both foundational and underappreciated. While André Breton and Paul Éluard often dominate discussions about Surrealism, Soupault’s work was just as vital in shaping the movement. His unique voice—introspective, dreamlike, and richly textured—helped establish a new poetic direction that influenced generations of writers.

This article explores Philippe Soupault’s role as a French poet within the context of 20th century literature. It examines his collaborations, literary experiments, and his evolving poetic philosophy. Comparisons with his contemporaries will further highlight his originality and importance.

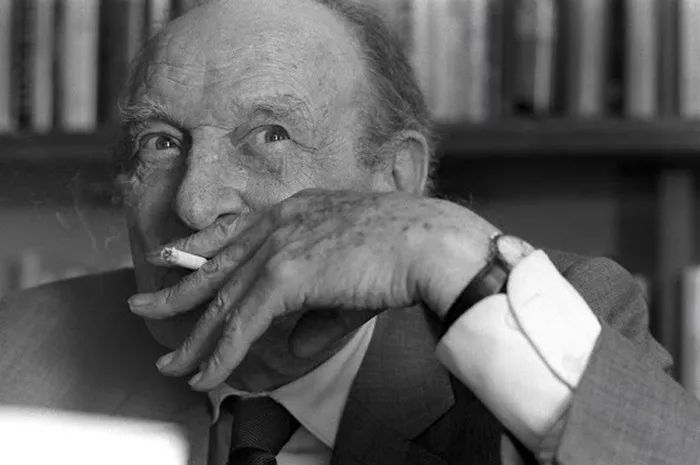

Philippe Soupault

Born in Chaville, France, in 1897, Philippe Soupault grew up in a bourgeois family that encouraged intellectual and artistic pursuits. As a young man, he was exposed to literature, music, and visual art. He studied at the Lycée Montaigne and later at the Lycée Fénelon, where he met future collaborators like André Breton.

World War I interrupted Soupault’s education, but the conflict also shaped his worldview. Like many 20th Century French poets, he became disillusioned with traditional institutions. He sought artistic freedom and innovation. This desire for transformation led him to the Dada movement.

Dada and the Birth of Literary Rebellion

Philippe Soupault was one of the early adopters of Dada in France. He contributed to several Dada journals and participated in its performances. For Soupault, Dadaism offered a way to confront the absurdities of modern life and the devastation of war. The movement’s rejection of logic and embrace of chaos appealed to his poetic sensibility.

However, Soupault’s Dadaist phase was relatively brief. While he appreciated Dada’s rebellious energy, he longed for a more structured method of exploring the unconscious. This quest would lead him to co-found the Surrealist movement.

The Magnetic Fields: A Surrealist Milestone

In 1920, Philippe Soupault and André Breton published Les Champs Magnétiques (The Magnetic Fields). This book is widely regarded as the first work of literary Surrealism. Using the technique of automatic writing, the two poets produced a text that flowed without rational control.

Les Champs Magnétiques broke new ground in French poetry. The writing was spontaneous, unpredictable, and deeply introspective. It aimed to tap into the subconscious mind, revealing hidden truths and emotional depths. As a 20th Century French poet, Soupault helped usher in a radical new method of composition.

Though The Magnetic Fields is often attributed more to Breton, Soupault’s voice is crucial. His lyrical style provided balance to Breton’s more cerebral tone. The book remains a cornerstone of Surrealist literature.

Break with Breton: Independence and Evolution

Despite their early collaboration, Soupault eventually distanced himself from André Breton and the increasingly dogmatic Surrealist group. While Breton wanted to tie Surrealism to Marxist politics, Soupault valued poetic freedom over ideological alignment.

In the 1930s, Soupault pursued solo projects and journalistic work. His poetry evolved to incorporate more personal and political themes. He became a prolific writer of novels, essays, and travel literature, while continuing to write poetry marked by introspection and emotional nuance.

His independence set him apart from many 20th Century French poets who aligned themselves strictly with Surrealist orthodoxy. Soupault preferred a more fluid, open-ended exploration of language and consciousness.

Major Works and Themes

Rose des vents (1920)

This early work reveals Soupault’s fascination with dream logic and sensory perception. The poems are rich in imagery and musicality. Unlike traditional French poetry, Rose des vents avoids rhyme and meter in favor of free verse.

Westwego (1921)

A travel-inspired prose poem, Westwego blends fiction and autobiography. It captures the poet’s experiences in the United States, offering a cross-cultural lens that was rare in French poetry at the time.

Georgia (1926)

In Georgia, Soupault continues his exploration of foreign lands and inner states. The poems reflect a synthesis of observation and imagination, making the personal universal.

Later Works

Soupault continued writing into the 1960s. His later poetry became more reflective, often meditating on time, memory, and mortality. His mature style is marked by clarity, emotional resonance, and philosophical depth.

Comparison with Contemporaries

André Breton

While both poets pioneered Surrealism, their approaches diverged. Breton was more theoretical, often writing manifestos and defining the rules of the movement. Soupault was more intuitive. He focused on the aesthetics of the poem rather than its ideological function.

Paul Éluard

Éluard’s poetry is known for its romantic and humanist qualities. Like Soupault, he used Surrealist techniques, but with more emotional transparency. Soupault’s work is more cerebral and abstract, though equally passionate.

Louis Aragon

Aragon’s political engagement contrasts sharply with Soupault’s personal introspection. Though they shared Surrealist roots, Aragon’s later embrace of Communism led to a different poetic trajectory.

Antonin Artaud

Artaud’s work is more extreme and theatrical. While Soupault explored the subconscious through lyricism, Artaud delved into madness and physical suffering. Their shared interest in inner experience connects them, but their styles and goals differ significantly.

Influence on French Poetry

Philippe Soupault helped redefine French poetry in the 20th century. His early adoption of automatic writing laid the groundwork for experimental forms. His independence from literary dogma inspired future poets to chart their own paths.

Soupault’s blending of poetic genres—merging essay, fiction, and reportage—also influenced later writers. He demonstrated that poetry could be both deeply personal and outward-looking, both emotional and intellectual.

His work is studied for its stylistic innovation and historical significance. Although less famous than some of his peers, he remains a foundational 20th Century French poet.

Journalism and Political Engagement

During the 1930s and 1940s, Soupault worked as a journalist. He reported from Europe and the Middle East, and his travels informed his writing. His journalism reflected a commitment to truth and empathy, qualities that also marked his poetry.

During World War II, Soupault joined the French Resistance. He was arrested by the Gestapo and imprisoned. These experiences deepened his poetic sensibility, imbuing his later work with themes of survival, freedom, and loss.

Legacy and Recognition

Though often overshadowed, Philippe Soupault has seen a resurgence in scholarly interest. His collected poems and essays are now more widely available. Critics have begun to reevaluate his contribution to French poetry and literary modernism.

In recent decades, universities and literary journals have acknowledged Soupault’s influence. His work is included in major anthologies of 20th Century French poetry. Exhibitions and retrospectives have also highlighted his role in the Surrealist movement.

His poetry continues to inspire. Contemporary poets cite Soupault for his openness, emotional range, and stylistic daring. His commitment to artistic freedom makes him a timeless figure in French literature.

Conclusion: The Quiet Revolutionary of French Poetry

Philippe Soupault was a 20th Century French poet who helped shape the direction of modern literature. From Dada to Surrealism and beyond, his work defied easy categorization. He remained true to his own voice, even when it meant standing apart from dominant trends.

As a French poet, Soupault championed the imagination, the unconscious, and the beauty of language. His poetry invites readers to see the world differently—to question, to feel, and to dream. Though his name may not be as widely recognized, his influence runs deep.

In the vast landscape of French poetry, Philippe Soupault stands as a quiet revolutionary. His legacy reminds us that innovation often begins in the margins, and that true artistry resists confinement. He remains essential reading for anyone interested in 20th Century French poetry and the enduring power of the poetic voice.