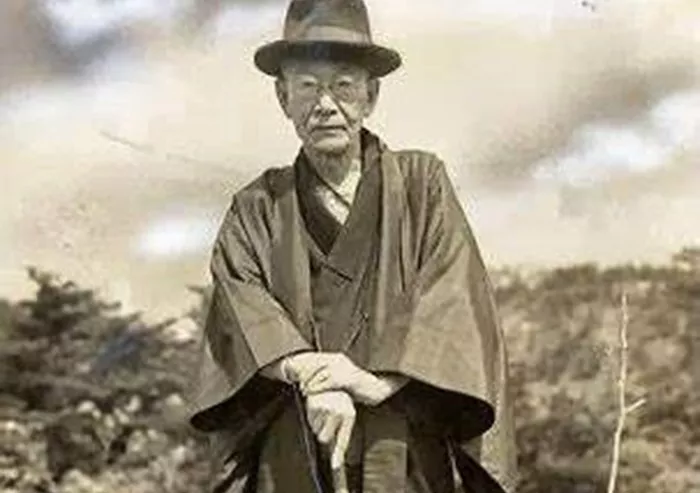

Among the many voices that shaped Japanese poetry in the early modern era, Murakami Kijō stands out for his quiet yet enduring contributions to the haiku form. A Japanese poet born in 1865, Kijō lived through a time of cultural transformation. Though his career began in the Meiji period, his poetic influence continued well into the 20th century. His work bridges traditional Japanese aesthetics with the realities of a rapidly modernizing society. Kijō’s poetry embodies the resilience and subtle grace of the spirit Japanese, positioning him among the more contemplative 20th century Japanese poets.

This article explores Murakami Kijō’s life, his contributions to Japanese poetry, and his place within the broader landscape of poets in 20th century Japan. The article also compares his work with his contemporaries to understand how different poetic voices responded to the tension between tradition and modernity.

Early Life and Influences

Murakami Kijō was born in 1865 in what is now Nagano Prefecture. His early years coincided with the final stages of the Tokugawa shogunate and the dawn of the Meiji Restoration. This historical backdrop shaped his sensibility as a poet. Like many Japanese poets of the time, Kijō received a classical education. He studied Chinese literature and traditional waka poetry. However, it was haiku that became his medium of expression.

Kijō’s life was marked by hardship. He lost his hearing due to illness at the age of 18, which may have deepened his introspective nature. Later, a house fire destroyed many of his personal belongings and early writings. These misfortunes found quiet expression in his haiku, which often evoke loss, solitude, and impermanence—themes central to Japanese poetry.

Haiku and the Evolution of Form

Murakami Kijō wrote in a time when haiku was evolving. Traditionally associated with Matsuo Bashō and the Edo period, haiku had long followed strict rules. However, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, poets began to challenge its limitations. Masaoka Shiki, often considered the father of modern haiku, led this reform. He argued for haiku as a form of personal expression rather than rigid stylization. Shiki also introduced the term shasei, or “sketch from life,” encouraging poets to observe the world directly.

Kijō was influenced by Shiki’s philosophy. He was not a direct disciple but shared Shiki’s appreciation for nature and everyday life. His haiku retained the 5-7-5 syllabic structure but focused on clarity and realism rather than ornate allusions. One of his most famous haiku reads:

First autumn morning

the mirror I stare into

shows my father’s face.

This verse is simple, yet powerful. It reflects the Buddhist concept of impermanence (mujō) and personal introspection, hallmarks of Japanese poetry.

Kijō Among His Contemporaries

To understand Murakami Kijō’s place among 20th century Japanese poets, it is helpful to consider his peers. Alongside him were poets like Takahama Kyoshi, Kawahigashi Hekigotō, and Ozaki Hōsai. Each of these poets took haiku in different directions.

Takahama Kyoshi, for example, upheld traditional seasonal references (kigo) and emphasized beauty and elegance in nature. He resisted some of Shiki’s reforms and believed in preserving the spiritual heritage of haiku. In contrast, Hekigotō experimented with free-style haiku, abandoning fixed syllabic patterns. Hōsai, known for his solitary life and Zen-influenced poems, stripped haiku down to its emotional core.

Kijō’s work stands somewhere in between. He did not reject tradition, but neither did he cling to it uncritically. His haiku were accessible, sincere, and deeply human. Compared to Kyoshi’s refined style, Kijō’s poems are more grounded. Compared to Hōsai’s radical minimalism, Kijō’s verses are more conventional, yet equally emotive.

Themes in Kijō’s Poetry

A distinguishing feature of Murakami Kijō’s haiku is the consistent presence of human emotion within natural imagery. While many Japanese poets used seasonal elements symbolically, Kijō gave them emotional weight. His poems often deal with time, memory, and the passage of life. These themes resonate with traditional Japanese concepts such as mono no aware—an awareness of the transience of things.

For instance:

Smoke of the grass fire—

even the things unseen

leave their traces still.

This haiku captures the ephemeral and invisible effects of existence. The image of a grass suggests fire destruction, but also renewal. It mirrors human experience: what we lose leaves traces in memory and feeling.

Another recurring theme in his poetry is solitude, not as loneliness but as a contemplative state. This distinguishes him from some urban-centered poets who were exploring social issues or experimenting with Western forms.

The Cultural Context of Early 20th Century Japan

Japan in the early 20th century was a nation in flux. The country was industrializing rapidly. Western influences were reshaping literature, philosophy, and daily life. Many 20th century Japanese poets responded to this shift in different ways. While modernist poets like Hagiwara Sakutarō explored free verse and psychological depth, haiku poets like Kijō maintained a quieter revolution—reforming form without abandoning heritage.

Kijō’s commitment to haiku can be seen as a cultural stance. He recognized the need for evolution, but within a framework that valued restraint, nature, and the subtlety of expression. His poetry offered readers a refuge in simplicity amidst the noise of modern life. In this way, he maintained the continuity of Japanese poetry while participating in its evolution.

Kijō’s Legacy and Influence

Though not as widely recognized outside Japan as Bashō or Shiki, Murakami Kijō remains respected among scholars and readers of Japanese poetry. His haiku are still included in anthologies and taught in schools. His emphasis on emotional authenticity within traditional form inspired later poets who sought to balance innovation with cultural continuity.

Contemporary Japanese poets, especially those working within the haiku tradition, often cite Kijō as an influence. His work is a reminder that even in times of change, poetic truth can be found in small, quiet moments.

Comparisons with Western Poets

Interestingly, Murakami Kijō’s sensibility finds echoes in Western poets of the early 20th century. Imagist poets like Ezra Pound and Amy Lowell advocated for clear, precise language and focused imagery. Their work parallels the shasei principle that Shiki and his followers, including Kijō, practiced.

Both traditions emphasized the power of a single image to convey deep meaning. However, where Imagists often embraced radical experimentation, Kijō’s style remained modest and reflective. This reflects a cultural difference: while Western modernism often pushed against tradition, Japanese modernism, particularly in poetry, sought harmony between past and present.

Conclusion

Murakami Kijō is an essential figure in the history of 20th century Japanese poets. His life and work represent a bridge between the classical past and the uncertain future of modern Japan. As a Japanese poet who experienced both personal hardship and cultural transformation, Kijō brought a depth of feeling and clarity of vision to his haiku. His commitment to tradition, tempered with quiet innovation, makes his work timeless.

In the broader landscape of Japanese poetry, Kijō’s legacy is one of subtle strength. He reminds us that poetic power does not always come from loud declarations or stylistic rebellion. Sometimes, it comes from a still moment, a remembered face, or the scent of autumn air. For readers seeking to understand the soul of 20th century Japanese poetry, Murakami Kijō offers a voice worth hearing—gentle, profound, and enduring.