Pierre-Joseph Bernard, affectionately known as Gentil-Bernard, is often remembered as a quintessential representative of 18th Century French poetry. His verse is elegant, sensual, and intimately connected to the intellectual and cultural movements of his age. As an 18th Century French poet, Bernard lived and wrote during the Enlightenment—a time when literature, philosophy, and the arts flourished under the influence of rationalism, humanism, and burgeoning secularism.

The nickname “Gentil-Bernard,” given by Voltaire, speaks to the poet’s refined charm and courteous manner, which was reflected in both his personality and his poetic output. In a century teeming with innovation and political change, Bernard stood out as a lyrical voice celebrating love, tenderness, and beauty—an embodiment of the more hedonistic and refined aspects of French Enlightenment culture.

French poetry in the 18th Century underwent significant transformation. Moving away from the grandiosity of 17th-century classicism, it embraced themes of individual pleasure, nature, and sentiment. Bernard played an important role in this literary shift, making his contributions to French poetry not just noteworthy but emblematic of broader cultural transitions.

Pierre-Joseph Bernard

Pierre-Joseph Bernard was born in Grenoble in 1708, the son of a modest family with strong provincial roots. Despite his humble beginnings, Bernard displayed early literary talent and intellectual curiosity. He received a sound education in classical literature and Latin, a foundation that would later influence his poetic works and translations.

Bernard moved to Paris to pursue a career in literature, a path that placed him at the heart of France’s artistic and cultural capital. Paris in the early 18th Century was a hub for poets, philosophers, and painters. Through strategic friendships and literary talent, Bernard found favor with patrons and entered elite intellectual circles. His acquaintance with prominent Enlightenment figures, such as Voltaire and the Marquise de Pompadour, allowed him to gain visibility and receive commissions.

One of Bernard’s early roles was as a translator and librettist. His translation work brought him prestige, especially for his sensitive and refined renditions of classical texts. His most famous commission was the libretto for Jean-Philippe Rameau’s opera Castor et Pollux, which premiered in 1737. This work demonstrated his skill in poetic composition and solidified his reputation as a literary figure of note.

Literary Style and Themes

Pierre-Joseph Bernard’s poetry is distinguished by its grace, lyricism, and classical balance. His language is clear and fluid, embodying the Enlightenment ideals of rational expression and aesthetic harmony. Bernard mastered the art of expressing delicate emotions with subtlety and refinement.

Themes of Love and Sensuality

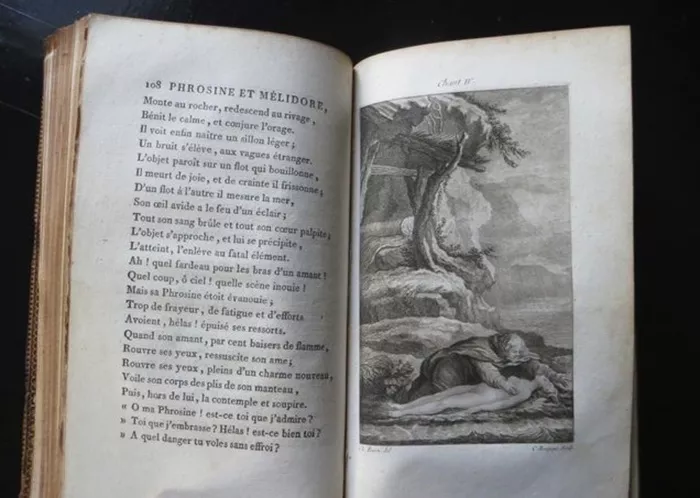

One of the most consistent themes in Bernard’s poetry is love—not the tragic or tormented love of later Romantic poets, but an elegant, joyful, often erotic celebration of intimacy. Bernard’s treatment of love is sensuous without being vulgar, playful without being trivial. His verse celebrates the physical and emotional pleasures of love in a manner that reflects the libertine spirit of the mid-18th Century.

This focus on love and sensuality aligned with the tastes of the French court, especially under Louis XV, where art and literature often revolved around courtly pleasures. Bernard’s poems often mirror this atmosphere, depicting lovers in pastoral settings, whispering sweet nothings beneath the trees or exchanging witty barbs over wine and music.

Refined Form and Structure

Bernard favored classical poetic forms such as the elegy, epigram, and ode. These forms allowed him to express emotion within a controlled, rhythmic framework. Unlike the more turbulent poetry that would emerge at the end of the century, Bernard’s work adheres to symmetry, proportion, and clarity—values inherited from the neoclassical tradition.

His use of the alexandrine (the twelve-syllable French line) is particularly skilled, and he often employed it to create a soft, flowing cadence. His verses rarely aim to provoke or agitate; instead, they invite contemplation and delight.

Mythological and Pastoral Imagery

Bernard often drew upon classical mythology and pastoral scenes to frame his poetic themes. References to Venus, Cupid, nymphs, and Arcadia abound in his work. These elements provided a timeless, idealized setting for his explorations of love and beauty, allowing him to echo the traditions of Horace, Ovid, and other Latin poets.

Contributions to French Poetry

Gentil-Bernard’s poetry may not have reshaped French literature in a revolutionary way, but his contributions were substantial in refining the poetic voice of the Enlightenment period.

Revitalizing the Elegy and Epigram

Bernard’s talent for short poetic forms helped reinvigorate the epigram and elegy, giving them new charm and

vitality. These forms, often overlooked in favor of longer epic or philosophical works, became fashionable again due to Bernard’s mastery. His poems, though brief, often carried an emotional punch, wrapping complex feelings in tight, elegant packages.

Bridging Classical and Enlightenment Values

Through his translations and original compositions, Bernard helped bridge the gap between classical antiquity and Enlightenment France. His translations of Horace and Ovid not only demonstrated his linguistic skill but also introduced classical erotic and pastoral themes to a new generation of French readers. This synthesis of classical form with Enlightenment ideals of clarity, wit, and worldly pleasure is a defining feature of 18th Century French poetry.

Literary Influence and Recognition

Bernard’s success with opera librettos, particularly with Castor et Pollux, also underscored his versatility. His work on this opera was praised for its poetic elegance and dramatic pacing, proving that poetry could thrive in both literary and performative settings.

He was admired by contemporaries and even dubbed “the French Anacreon” for his lyrical and amorous style. His influence can be traced in the works of later 18th Century poets who sought to blend the sensual with the sophisticated, the emotional with the intellectual.

Comparing Bernard with Contemporaries

Voltaire

Voltaire, perhaps the most famous French literary figure of the 18th Century, used poetry as a weapon. His verse was sharp, satirical, and politically charged. Bernard’s poetry, by contrast, was apolitical and lyrical. While Voltaire railed against injustice and superstition, Bernard immersed his readers in romantic escapades and pastoral delights. The comparison highlights the diversity within French poetry of the period—ranging from philosophical critique to the exploration of sensual beauty.

Jean-Baptiste Rousseau

Jean-Baptiste Rousseau, another early 18th Century French poet, shared Bernard’s love for classical form. However, Rousseau’s verse often bore a melancholic and moralizing tone. Bernard’s poems rarely touch on grief or morality; they are light-hearted, even indulgent. While Rousseau looked backward to moral order, Bernard gazed forward—or inward—toward pleasure and personal expression.

André Chénier

André Chénier, active at the end of the 18th Century, was among the poets who began to break from neoclassicism and move toward Romanticism. Chénier introduced more emotional intensity and political engagement into French poetry. Bernard’s work can be seen as a precursor to Chénier’s, especially in its emphasis on personal feeling and classical motifs. However, Bernard lacked the revolutionary fervor and tragic depth that characterized Chénier’s poetry.

The Role of French Poetry in the 18th Century

French poetry in the 18th Century was both a mirror and a molder of its cultural milieu. Poets were expected to be both artists and intellectuals. Poetry was not just a private indulgence but a public act of shaping taste, opinion, and identity.

Poetry and the Enlightenment

The Enlightenment emphasized clarity, rationality, and elegance—all qualities that Bernard exemplified in his writing. But the Enlightenment was also about liberty and the challenge to tradition. In this regard, Bernard’s poetry may seem less revolutionary, but his celebration of sensuality and personal pleasure was itself a form of quiet rebellion against the more rigid moral codes of earlier eras.

Audience and Reception

French poets of this period were often dependent on patronage, and Bernard was no exception. His works were popular among the elite, especially those connected with the court of Louis XV. His light eroticism, pastoral escapism, and lyrical sweetness appealed to an audience seeking refinement and entertainment rather than philosophical depth.

Legacy of Pierre-Joseph Bernard

Today, Pierre-Joseph Bernard may not be a household name, but his work remains an important part of the tapestry of 18th Century French poetry. His verse offers a valuable lens through which we can understand the values, aesthetics, and pleasures of Enlightenment France.

Preserving Poetic Grace

Bernard’s commitment to grace and balance helped preserve the poetic ideals of classical antiquity even as France moved toward Romanticism. He showed that poetry could be emotionally expressive without being bombastic, sensually rich without being obscene, and intellectually elegant without being cold.

Influence on French Literary Tradition

His influence can be felt not only in poetry but in French opera and the broader cultural embrace of lyricism and elegance. He occupies a space between the moralists of the early 18th Century and the Romantics who would emerge later, making him a transitional and transformative figure.

Conclusion

Pierre-Joseph Bernard stands as a graceful and refined voice among 18th Century French poets. His poetry is not grand or revolutionary, but it is undeniably beautiful anl of feeling. He embraced the Enlightenment’s love of elegance, reason, and sensuality, and he conveyed these values through verses that remain fresh and vivid even today.

As a French poet, Bernard helped define the sensibility of his time. His contribution to French poetry lies not in radical innovation but in the perfection of form, the delicacy of emotion, and the art of poetic pleasure. In celebrating love and life with refinement, he captured the spirit of a vibrant and complex age—an age where beauty and reason danced hand in hand.