In the complex mosaic of 19th century Greek poets, one figure who stands out for his blend of ecclesiastical gravitas and lyrical depth is Chrysanthos of Madytos. Born in 1770 in the small town of Madytos near the Hellespont, Chrysanthos developed his literary identity during a time of immense social and political upheaval. Though best known as a music theorist and scholar of ecclesiastical chant, he was also a Greek poet whose contributions helped shape the spiritual tone of modern Greek poetry in a transitional era. His work bridges the late Ottoman period with the intellectual awakening that accompanied Greece’s War of Independence and its long path toward nationhood.

This article examines the literary and historical context of Chrysanthos’s poetry. It compares his style and themes with other 19th century Greek poets, providing a critical lens on the broader cultural and ideological forces of his time. In doing so, it places Chrysanthos in dialogue with both his contemporaries and the larger tradition of Greek poetry.

Historical and Cultural Context

The 19th century was a period of revival and reinvention in Greek letters. After centuries under Ottoman rule, the Greek people experienced a cultural renaissance that found expression in both revolutionary zeal and literary experimentation. The Greek War of Independence, which began in 1821, was not only a political struggle but also a symbolic reclamation of a classical and Byzantine past. Poetry became one of the main instruments of national identity.

Greek poets of this century often drew on themes of patriotism, exile, and religious faith. These themes were rooted in both ancient tradition and lived experience. Against this background, Chrysanthos of Madytos composed poetry with a distinct voice that combined ecclesiastical solemnity with historical awareness. As a deacon, theologian, and music theorist, he infused his verse with the cadences and vocabulary of Orthodox liturgy, offering a unique variation on the poetic norms of his time.

The Life and Work of Chrysanthos

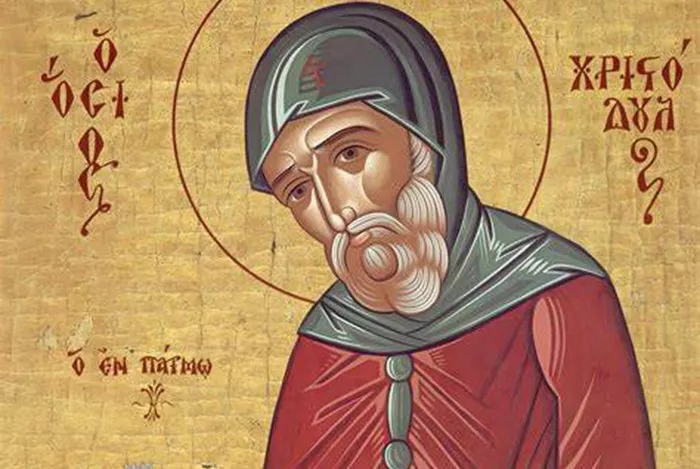

Chrysanthos was educated at the Patriarchal School of Constantinople, one of the leading centers of Orthodox scholarship. He became a hierodeacon and later the protopsaltis (chief cantor) of the Great Church of Christ. His most famous written work is Theoretical and Practical Manual of Music, which laid the foundation for the modern notation system used in Byzantine chant. However, lesser known are his poetic compositions, often embedded in theological commentary or liturgical contexts.

His poetry reflects a Byzantine sensibility. It is steeped in theological symbolism, metrical chant, and the rhythm of Orthodox services. His verses did not aim for the romantic individualism common among Western poets of the same era. Instead, he employed a collective voice—a voice of a people yearning for spiritual and cultural renewal.

Themes in Chrysanthos’s Poetry

Several recurring themes characterize the poetry of Chrysanthos. Among them are:

Divine Order and Cosmic Harmony: Drawing from his knowledge of ecclesiastical music, Chrysanthos often linked the divine with the harmonic structure of the universe. His poems describe a cosmos where music, faith, and nature coalesce into a single divine expression.

Byzantine Nostalgia: He mourns the fall of Constantinople and laments the loss of a sacred imperial past. This is not merely a historical mourning, but a spiritual one. His verses seek to rekindle the Byzantine Christian spirit in an age overshadowed by foreign domination and secular ideologies.

Sacred Liturgy as Art: Chrysanthos did not separate poetry from liturgy. He saw them as mutually reinforcing. His poetic work often mirrors the structure of hymns, complete with refrains, responsive verses, and theological motifs. The musicality of his language, derived from chant, marks a distinct mode of expression among 19th century Greek poets.

National Identity Through Faith: While not overtly political, Chrysanthos’s poetry indirectly supports the national cause. For him, true Greek identity is Orthodox Christian identity. In this sense, his work participates in the broader movement of cultural nationalism.

Comparison with Contemporary Greek Poets

To understand Chrysanthos’s contribution, it is useful to compare him with other notable 19th century Greek poets, such as Dionysios Solomos, Andreas Kalvos, and Alexandros Rizos Rangavis.

Dionysios Solomos (1798–1857) is often considered the national poet of Greece. His work, especially The Hymn to Liberty, became a symbol of Greek independence. Solomos wrote in Demotic Greek and drew on Enlightenment ideas, Romanticism, and classical heritage. Unlike Chrysanthos, Solomos was deeply influenced by Western European literature and philosophies. While Solomos celebrated the heroism and suffering of the common Greek people, Chrysanthos turned inward, toward spiritual contemplation and liturgical traditions.

Andreas Kalvos (1792–1869) also wrote in a romantic and patriotic vein. Like Solomos, he was a child of the diaspora who returned to contribute to the Greek cause. Kalvos’s odes often dealt with virtue, sacrifice, and glory. His poetry uses elevated diction and classical forms. Yet, his engagement with Christian themes is less liturgical and more moralistic, unlike the theological depth in Chrysanthos’s work.

Alexandros Rizos Rangavis (1809–1892), on the other hand, was more academic and neoclassical in his orientation. A scholar and diplomat, Rangavis aimed to create a modern Greek literature that harmonized with European norms. He favored Katharevousa—a purified form of Greek that approximated ancient models. Chrysanthos, though a traditionalist, did not share Rangavis’s interest in language reform for secular purposes. His poetic Greek was closer to the ecclesiastical idiom of the Orthodox Church.

The contrast between these poets highlights the diversity of 19th century Greek poetry. Chrysanthos stood apart from the rising tide of secular nationalism and Western-inspired romanticism. He offered a vision rooted in Orthodox cosmology and the Byzantine past. While other poets focused on liberation, Chrysanthos emphasized illumination.

Language and Style

The language of Chrysanthos’s poetry is formal, sometimes archaic, and always musical. He preferred terms drawn from scripture, liturgy, and patristic theology. His sentences are often long, with a rhythmic structure suitable for chanting. This sets him apart from Solomos, who championed the vernacular, or Kalvos, who sought a new poetic diction based on classical models.

Yet, Chrysanthos’s style was not static. He adapted elements of modern Greek poetic sensibility when addressing contemporary themes, such as the longing for freedom or the dignity of martyrdom. His gift lay in his ability to speak to the present through the voice of tradition.

In this sense, he can be seen as a precursor to later poets like Angelos Sikelianos, who also explored the sacred and national as intertwined forces. Chrysanthos anticipated the spiritual nationalism that would later emerge in 20th century Greek poetry.

The Enduring Legacy

Though not widely known outside specialist circles, Chrysanthos of Madytos holds a special place in the canon of 19th century Greek poets. His fusion of liturgy and lyricism created a distinctive poetic voice. For Orthodox communities, his verses resonate as spiritual hymns rather than literary compositions. Yet, for literary historians, his work offers a vital link between the Byzantine tradition and modern Greek poetry.

His contribution is particularly important for understanding how Greek poetry evolved not only through political revolution but also through religious continuity. Chrysanthos reminds us that Greek identity was shaped not only by ancient Athens and modern Europe but also by the monasteries of Mount Athos and the choir stalls of Constantinople.

Today, his work invites renewed scholarly attention. As interest grows in the intersections of religion, identity, and culture in Southeastern Europe, Chrysanthos emerges as a figure of renewed relevance. His life and poetry demonstrate that the roots of modern Greek poetry are as much spiritual as they are political or classical.

Conclusion

The story of 19th century Greek poets is rich, layered, and full of contrasts. In this story, Chrysanthos of Madytos plays a unique role. He was not a revolutionary poet in the conventional sense, yet his poetry participates in the deeper revolution of cultural memory and spiritual revival. He drew on ancient and Byzantine sources to offer a poetic vision grounded in the eternal rather than the ephemeral.

By comparing him with contemporaries such as Solomos, Kalvos, and Rangavis, we see how varied Greek poetry could be during this century. Each poet responded to the national and cultural questions of their time in their own way. Chrysanthos’s response was to turn to the sacred, to the liturgical, and to the musical. His work remains a testament to the enduring power of faith, music, and memory in shaping poetic expression.

As scholars continue to explore the literary heritage of Greece, the name of Chrysanthos of Madytos deserves to be spoken not only in ecclesiastical history but also in the broader narrative of Greek poetry. His legacy proves that even in the age of revolutions, the ancient rhythms of chant and prayer could still move hearts and illuminate minds.