The 20th century was a time of great transformation in Japan. From the aftermath of Meiji-era modernization to the devastating impact of World War II and the rise of a post-war cultural identity, Japanese poets lived through dramatic social and political changes. One poet who emerged during this turbulent time was Otokichi Ozaki, born in 1904. Although not as internationally known as some of his contemporaries, Ozaki holds a distinctive place among 20th century Japanese poets due to the quiet intensity and subtle innovation in his work. This article explores his poetic voice within the larger context of Japanese poetry, drawing comparisons with others of his generation to offer a deeper understanding of his contributions.

Historical Context of Japanese Poetry in the 20th Century

Japanese poetry underwent profound shifts during the 20th century. The era was marked by the decline of traditional forms such as waka and haiku, and the rise of shi (modern-style poetry). Western literary influences became increasingly visible, particularly after World War I, when poets began experimenting with free verse and new subject matter.

This period also saw the emergence of literary movements such as Shinkō Shi (New Poetry), which sought to break from the constraints of classical Japanese forms. The movement was influenced by French Symbolism, Russian Futurism, and the works of English-language poets like T.S. Eliot and W.B. Yeats. These foreign currents encouraged Japanese poets to re-express their cultural identity in fresh and sometimes radical ways.

Otokichi Ozaki was shaped by this shifting literary landscape. Born into a Japan that was already open to global ideas yet still rooted in feudal traditions, Ozaki represents a generation of Japanese poets who tried to reconcile the ancient with the modern, the national with the universal.

The Life and Work of Otokichi Ozaki

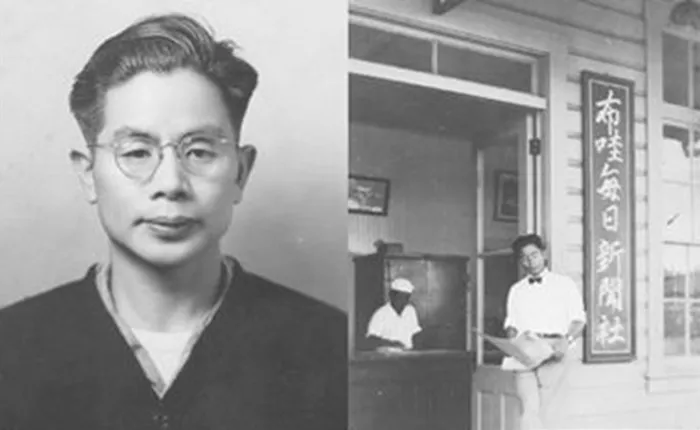

Little is known about the personal life of Otokichi Ozaki, which makes the interpretation of his poetry all the more essential in understanding his place in the canon of 20th century Japanese poets. What survives is a body of work that reflects inner restraint and contemplative depth. Ozaki’s poetry does not shout; it whispers with elegance.

He began writing in the 1920s, a time when Japan was exploring liberal democracy under the Taishō period. His early work shows a strong awareness of nature, but not in the romantic or pastoral tradition. Instead, nature appears in his poems as a mirror for internal emotional states—fog becomes confusion, wind becomes longing, silence becomes despair.

As he matured as a poet, Ozaki’s verse became more refined, more abstract. He moved away from syllabic constraints, favoring shi to explore themes of alienation, impermanence, and human vulnerability. In doing so, he placed himself in dialogue with poets such as Hagiwara Sakutarō, often regarded as the father of modern Japanese poetry. While Hagiwara’s work was more overtly psychological and fragmented, Ozaki’s poems maintained a certain traditional polish even when adopting modern forms.

Language, Form, and Imagery

A close reading of Ozaki’s work reveals his mastery of simple yet profound language. His poetry frequently employs repetition, minimalism, and carefully constructed images. A short poem from his middle period reads:

“The crow flies

without question—

dusk deepens.”

Here, the image is spare, yet heavy with implication. The crow, a common symbol in Japanese literature, might represent fate, solitude, or death. The “dusk” suggests the passage of time or the end of something. The absence of punctuation allows multiple interpretations, a hallmark of high-quality Japanese poetry.

Ozaki was also known for his use of kigo, or seasonal words, which rooted his modern expressions in classical traditions. Yet, unlike older poets such as Matsuo Bashō, who used seasonal references to evoke harmony with nature, Ozaki used them to signal disconnection. A falling leaf, in his poetry, is not just a natural event; it is a metaphor for emotional decay.

His poems often occupy the space between silence and sound. They read like whispers from another room—present, elusive, and emotionally resonant.

Comparison with Other 20th Century Japanese Poets

In understanding Ozaki’s unique voice, it is useful to compare him with other Japanese poets of the 20th century. As mentioned, Hagiwara Sakutarō was a dominant force. His collection “Howling at the Moon” (1917) broke many literary conventions and set the tone for psychological modernism in Japanese poetry. Hagiwara’s language was raw, experimental, and deeply personal.

In contrast, Ozaki’s poetry shows restraint. He was more aligned in tone with Yasano Akiko, who, though best known for her earlier tanka, also engaged in modernist expression. Both poets used personal experience to explore broader human themes, though Akiko’s was often erotic or feminist, while Ozaki’s remained existential and solitary.

Miyazawa Kenji, another notable contemporary, infused his poetry with mysticism and moral idealism, often using rural settings and Buddhist philosophy. Ozaki shared the minimalist aesthetic but lacked Kenji’s overt spirituality. Instead, he offered a kind of poetic secularism—a quiet exploration of meaning without religious framework.

Later poets such as Tanikawa Shuntarō brought a lighter, more playful tone to post-war Japanese poetry. In this context, Ozaki can be seen as a bridge figure, connecting the heavy introspection of early modernists with the more flexible voices of the post-war generation.

Themes in Ozaki’s Poetry

The dominant themes in Otokichi Ozaki’s work reflect both personal and collective preoccupations of 20th century Japanese poets. These include:

Impermanence– A Buddhist concept deeply rooted in Japanese aesthetics. Ozaki’s work frequently returns to the fleeting nature of time, relationships, and identity.

Alienation and Silence – Many poems are populated by solitary figures, sparse dialogue, and muted tones. This gives his work a haunting quality.

Nature as Inner Landscape – Though inspired by external environments, his nature imagery often mirrors emotional states. The sea may be calm, but inside, the subject is in turmoil.

Post-war Disillusionment – While he wrote before and after World War II, some of his later works reflect the disorientation felt in Japan’s cultural psyche. The optimism of early modernization gave way to confusion and loss.

These themes were not unique to Ozaki, but his treatment of them was uniquely subtle. In a literary culture that includes extremes—from Bashō’s precise beauty to Hagiwara’s chaotic emotion—Ozaki’s voice is one of contemplative balance.

Influence and Legacy

Though Otokichi Ozaki never reached the fame of poets like Hagiwara or Tanikawa, his influence is felt in the quiet evolution of Japanese poetry. He represents a school of thought that values introspection, discipline, and economy of language. In a century where poetry became increasingly globalized and experimental, Ozaki remained committed to the integrity of the poetic moment.

Younger poets, particularly those writing in the 1970s and 1980s, have cited his work as an influence, especially in how to handle emotion with restraint. Scholars of Japanese literature have begun to reassess his place in the canon, emphasizing how his poems serve as a counterpoint to louder or more political voices.

His work is often included in anthologies of modern Japanese poetry, though few complete translations exist. For non-Japanese readers, this presents a challenge. But for scholars and poets who engage with the original texts, Ozaki offers a rich and rewarding study in how tradition and modernity can coexist.

Conclusion

Otokichi Ozaki stands as a significant though understated figure among 20th century Japanese poets. His work offers a compelling example of how Japanese poetry evolved through a century of unprecedented change. While other poets of his time embraced chaos, experimentation, or overt political messaging, Ozaki remained quietly focused on the craft of poetry itself. Through his measured language, deep imagery, and philosophical themes, he adds a valuable voice to the diverse chorus of modern Japanese literature.

The 20th century was a golden yet troubled age for Japanese poetry. It witnessed the decline of certain forms, the rise of others, and the ongoing negotiation between past and present. In this continuum, Otokichi Ozaki occupies a place of poetic stillness—a reminder that in a noisy world, there is still power in silence.

By examining his life and work, we gain not only insight into his unique poetic vision but also a broader understanding of what it meant to be a Japanese poet in the 20th century. His legacy invites us to consider poetry not just as an art form, but as a way of being in the world—quiet, attentive, and deeply human.