The 18th century was a time of intellectual, political, and artistic transformation in France. French poetry, like other branches of literature and philosophy during this period, was undergoing dynamic changes. Enlightenment thinkers and writers dominated the cultural stage, and poets were increasingly called upon to reflect the spirit of reason, nature, and society. It was in this vibrant context that Jean-Antoine Roucher emerged—a poet both shaped by and contributing to the shifting tides of 18th century French literature.

Jean-Antoine Roucher was a French poet best known for his long didactic poem Les Mois (The Months). Born in Montpellier in 1745 and executed during the French Revolution in 1794, Roucher lived in a century where literature became a medium for political and moral reflection. His poetry, deeply classical in structure yet modern in theme, is an essential contribution to the era of Enlightenment literature.

This article will explore Roucher’s life, major works, literary influences, and his place within the larger context of 18th century French poetry. Through comparison with his contemporaries, such as André Chénier and Voltaire, we will understand the unique voice Roucher brought to the poetic tradition of his time.

Jean-Antoine Roucher

Jean-Antoine Roucher was born on February 22, 1745, in Montpellier, a city known for its intellectual and cultural heritage. His early education reflected the Enlightenment ideals of reason and scientific curiosity. He was well-versed in the classical languages, Latin and Greek, and admired ancient poets such as Virgil and Horace. This classical foundation would become evident in his poetic style, particularly in Les Mois, which mirrors the Georgic tradition.

Roucher moved to Paris in 1770 to pursue a literary career. Like many young poets of his time, he was drawn to the intellectual salons of the capital, where philosophical ideas and literary trends flourished. There, he established relationships with leading Enlightenment figures, including Diderot and Voltaire. However, Roucher remained more conservative in his poetic style compared to some of the more radical writers of his day.

Les Mois: Roucher’s Masterpiece

Structure and Theme

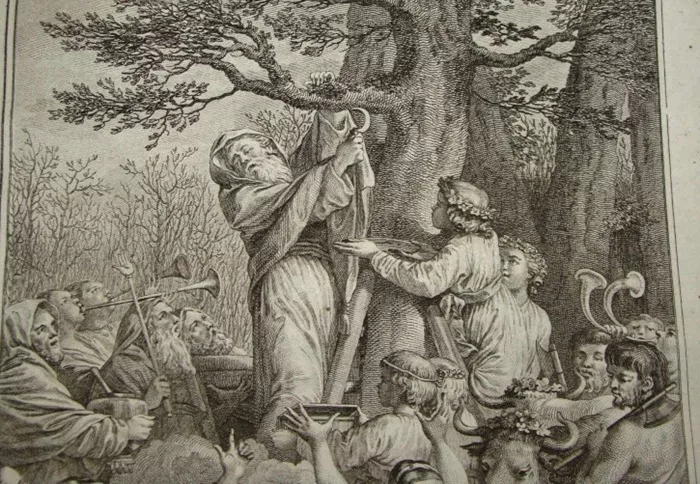

Les Mois is Roucher’s most significant contribution to French poetry. Composed between 1774 and 1779, and published in 1780, this twelve-part poem reflects on the changing seasons and rural life. Each section is dedicated to one month of the year, drawing from classical models like Virgil’s Georgics. The poem merges a love for nature with moral and philosophical reflection.

The structure of Les Mois is didactic, aiming to teach readers about nature, agriculture, and virtue. Each month brings its own set of reflections on rural labor, family life, and the cycles of growth and decay. This blend of poetic beauty and moral instruction was characteristic of Enlightenment-era literature.

Language and Style

Roucher’s style in Les Mois is classical and harmonious. He employs alexandrine verse, a twelve-syllable metrical line typical of French classical poetry. His diction is elevated yet clear, allowing his philosophical insights to resonate without becoming obscure.

Unlike some of his contemporaries, Roucher did not embrace radical innovation in poetic form. Instead, he refined traditional methods to express contemporary concerns. His poetry advocates for reason, harmony with nature, and the moral value of labor—all themes central to Enlightenment thinking.

Roucher and the Enlightenment

As an 18th century French poet, Roucher was deeply influenced by Enlightenment ideals. However, he was not a philosopher-poet in the mold of Voltaire or Diderot. His work is more reflective than polemical. While Voltaire used satire to criticize religion and government, Roucher used poetry to celebrate rural life and moral virtue.

Roucher’s Les Mois reflects Rousseau’s influence, particularly the belief in the moral purity of the natural world. Like Rousseau, Roucher saw the countryside as a source of truth and virtue, in contrast to the corruption of urban life. Yet, unlike Rousseau’s passionate rhetoric, Roucher’s tone is more measured, guided by classical restraint.

Roucher also maintained a cautious distance from the more radical political ideologies of the time. Although he sympathized with calls for reform, he feared the excesses of revolution. This ambivalence would later prove fatal, as he was executed during the Reign of Terror, accused of counter-revolutionary sympathies.

Comparison with Other 18th Century French Poets

André Chénier

André Chénier (1762–1794) is often compared with Jean-Antoine Roucher due to their similar fates and poetic styles. Both were executed during the French Revolution and wrote poetry marked by classical influence and Enlightenment thought. However, Chénier’s verse was more experimental and emotionally charged. His fragments and odes show a greater affinity for Romantic sensibility, while Roucher remained firmly rooted in classical harmony.

Chénier’s imagery is often more vivid, and his tone more impassioned. In contrast, Roucher’s poetry is calm, reflective, and morally didactic. Where Chénier anticipates Romanticism, Roucher embodies the Enlightenment ideal of reason.

Voltaire

Voltaire (1694–1778) was perhaps the most influential literary figure of the French Enlightenment. Though better known for his prose and philosophical works, Voltaire was also a prolific poet. His poetry was sharp, witty, and often satirical, targeting the Church and monarchy.

Roucher’s work is devoid of Voltaire’s biting satire. His poetry is not meant to provoke but to elevate. In this sense, Roucher represents a more harmonious and less confrontational aspect of 18th century French poetry.

Évariste de Parny

Another important figure is Évariste de Parny (1753–1814), known for his elegies and love poetry. Parny introduced a more intimate and emotional tone to French verse, laying the groundwork for Romanticism. Compared to Parny, Roucher seems distant and didactic. While Parny turned inward, exploring personal emotion, Roucher looked outward to nature and society.

Roucher’s Legacy in French Poetry

Although Jean-Antoine Roucher is not as widely read today as some of his contemporaries, his contributions to 18th century French poetry are significant. He represents a transitional figure—deeply rooted in classical traditions yet concerned with Enlightenment values. His commitment to order, harmony, and virtue made him a poet of his time, even as the times changed drastically around him.

His death during the French Revolution marked the end of an era. Roucher’s poetry, particularly Les Mois, remains a valuable document of Enlightenment thought rendered in poetic form. His legacy is one of moral clarity, literary discipline, and a deep love of nature.

Execution and Final Days

In 1794, during the height of the Reign of Terror, Roucher was arrested for allegedly supporting counter-revolutionary ideas. Like many intellectuals who were seen as moderate, he fell victim to the purges of the Jacobin regime. He was guillotined on July 25, 1794, just days before the fall of Robespierre.

Roucher’s execution is a poignant reminder of the dangers poets and thinkers faced during revolutionary upheaval. He died alongside André Chénier, another poet whose classical verse and moderate views made him suspect in the eyes of extremists.

Roucher’s Influence on Later Generations

Roucher’s influence on later French poetry is subtle but real. While he did not found a school or movement, his devotion to moral instruction and natural beauty informed the work of early 19th-century poets. Some Romantic poets, though more emotional in tone, admired Roucher’s depiction of nature and rural life.

His use of didactic poetry as a tool for social commentary inspired later poets to consider the social function of art. Even if his poetic style became old-fashioned by Romantic standards, the integrity of his vision remained admired.

Conclusion

Jean-Antoine Roucher was a French poet who lived and wrote at the intersection of tradition and transformation. As an 18th century French poet, he upheld the classical ideals of harmony and order while engaging with Enlightenment concerns about nature, virtue, and reason. His poetry reflects a world still tethered to classical models yet increasingly open to new ideas.

Les Mois stands as his greatest achievement, a work that combines poetic form with philosophical depth. Though overshadowed by more radical or romantic figures, Roucher deserves a place in the history of French poetry. He reminds us that poetry can be both beautiful and instructive, both traditional and engaged with its time.

In comparing him with contemporaries like Chénier, Voltaire, and Parny, we see Roucher’s unique position. He is not the most dramatic or innovative, but he is among the most consistent and morally serious. His legacy is one of balance—a poetic equilibrium between nature and reason, art and ethics, tradition and progress.

Through his life and work, Jean-Antoine Roucher embodies the complex spirit of 18th century French poetry. His voice continues to echo as a reminder of poetry’s enduring power to reflect, inspire, and endure even in the face of revolution.