Jean Chapelain, a prominent 17th Century French poet, occupies a unique position in the literary history of France. Though not celebrated today for the enduring beauty of his verse, Chapelain was a central figure in shaping the trajectory of French poetry and literary criticism in the Classical Age. His reputation rested more on his theoretical and organizational contributions than on his poetic mastery. He was a member of the newly founded Académie française, a key player in establishing standards for the French literary canon, and a trusted literary advisor to Cardinal Richelieu.

This article will examine Chapelain’s life, poetic works, influence on 17th Century French poetry, and legacy. It will also compare him to contemporaries like François de Malherbe and Pierre Corneille, highlighting how Chapelain’s philosophical and literary ideals differed from, and sometimes conflicted with, other literary voices of his time.

Jean Chapelain

Jean Chapelain was born in Paris on December 4, 1595. He came from a bourgeois family, and his father, a notary, initially intended his son for a legal career. However, Chapelain showed a stronger interest in letters, especially in classical literature and languages. He received a rigorous education, grounded in Latin and Greek, which shaped his intellectual and poetic development.

Under the guidance of Nicolas Bourbon, a neo-Latin poet and scholar, Chapelain became steeped in the rhetorical and literary traditions of antiquity. These early studies had a lasting effect on his belief in literary decorum and poetic rules—concepts that would come to define his contributions to French poetry.

The Role of a Critic and Organizer

Unlike many 17th Century French poets, Chapelain made his name not through the brilliance of his verse, but through his organizational skill and deep commitment to literary reform. His prose writings, letters, and theoretical essays made him a leading figure in the Classical movement. Chapelain believed that French literature needed structure and guidance. For him, the greatness of ancient Greece and Rome could be recaptured only through discipline, imitation, and conformity to rules.

He played an instrumental role in the foundation of the Académie française, established in 1635 under the patronage of Cardinal Richelieu. Chapelain contributed significantly to the Académie’s mission: to regulate and refine the French language and literature. He also helped draft the Académie’s statutes and was tasked with compiling its first official dictionary. Through these efforts, Chapelain’s influence on French poetry extended beyond his own verse.

Theoretical Foundations: Doctrine and Decorum

Chapelain was a staunch advocate of poetic rules. His views aligned with the larger movement of Classicism, which emphasized rationality, order, clarity, and unity. In the poetic realm, this translated into adherence to Aristotle’s Poetics and Horace’s Ars Poetica. Chapelain believed that poetry should instruct as well as delight, and he called for a return to the principles of unity of time, place, and action in drama and epic poetry.

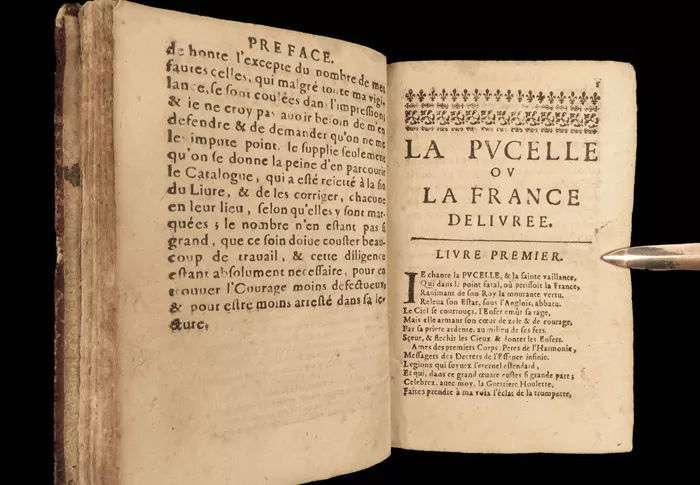

In 1630, Chapelain wrote a critical preface to his proposed epic poem, La Pucelle, where he outlined his poetic principles. He criticized the baroque extravagance of earlier poets and praised Malherbe, who had tried to purify French verse from excess. Chapelain’s essay served as a key manifesto for the Classical school and offered a template for how poets should write: with clarity, moral purpose, and respect for the ancients.

La Pucelle: The Ambitious but Failed Epic

Chapelain’s most famous poetic endeavor, La Pucelle (“The Maid”), was meant to be the great national epic of French poetry, telling the story of Joan of Arc. Encouraged by Richelieu and supported by the court, Chapelain labored on the work for many years. When the first twelve cantos were finally published in 1656, the anticipation was immense. The poem quickly sold out, aided by Chapelain’s reputation and political connections.

However, the literary reception was overwhelmingly negative. Critics panned the poem for its stiffness, lack of imagination, and awkward versification. Boileau, the foremost literary critic of the later 17th century, dismissed La Pucelle as an embarrassment. The project, initially meant to crown Chapelain’s career, became a symbol of failure. He never completed the rest of the poem and ceased writing verse altogether.

This failure, though damaging to his poetic reputation, did not erase Chapelain’s importance as a critic and intellectual. His theoretical writings continued to shape the direction of 17th Century French poetry, particularly through the Académie française and his patronage decisions.

Patronage and Literary Networks

One of Chapelain’s most enduring contributions to French letters was his role as a literary advisor and patronage mediator. Richelieu trusted Chapelain’s judgment and often consulted him on literary appointments andpensions. Later, under Louis XIV, Chapelain became a key figure in the distribution of royal pensions to writers.

Chapelain used this position to reward and elevate writers he believed upheld Classical ideals. He supported figures such as Jean de La Fontaine and Charles Perrault, helping to shape the tastes of the age. His correspondence reveals a methodical and principled approach to literary evaluation—one that tried to balance artistic merit with moral and national purpose.

In this sense, Chapelain was more than just a French poet; he was a cultural gatekeeper. While he lacked the creative genius of Racine or Molière, he helped define the ecosystem in which such poets thrived.

Comparisons with Contemporary Poets

Chapelain and Malherbe

François de Malherbe was an earlier reformer of French poetry and a major influence on Chapelain. Malherbe’s emphasis on linguistic purity, metrical regularity, and rhetorical restraint found a devoted follower in Chapelain. However, where Malherbe was a craftsman of verse, Chapelain was more of a theorist. Malherbe’s poetry, though austere, had a lyrical and emotional power that Chapelain’s verse lacked.

Chapelain admired Malherbe’s efforts to “cleanse” French poetry of its medieval and Renaissance excesses. Yet Malherbe’s vision was more poetic than Chapelain’s didactic one. The latter pushed further into theory, sacrificing poetic spontaneity for the sake of structure.

Chapelain and Corneille

Pierre Corneille, best known for his tragedies like Le Cid, represents a more dramatic and independent voice among 17th Century French poets. Chapelain was one of Corneille’s early critics, particularly during the Le Cid controversy. Chapelain found the play lacking in adherence to the Classical unities and moral decorum.

Corneille, by contrast, favored emotional complexity and dramatic freedom. His genius lay in transcending rules without undermining them. The Le Cid affair exposed the limitations of Chapelain’s rigid Classical outlook. While Chapelain tried to standardize poetry through criticism, Corneille showed that poetic greatness often required breaking the rules.

Chapelain and Boileau

Nicolas Boileau, the later champion of Classical poetics, had little patience for Chapelain’s actual poetry. Though Boileau agreed with Chapelain’s views on decorum and Classical structure, he mocked La Pucelle and derided Chapelain’s literary taste.

The irony is that Chapelain’s theoretical groundwork helped pave the way for Boileau’s more refined synthesis of Classical poetics. Without Chapelain’s early efforts to establish critical norms, Boileau might not have had such a fertile ground to build upon.

Chapelain’s Place in the Classical Tradition

Chapelain occupies a paradoxical position in the history of French poetry. On the one hand, he was not a successful poet. His verse lacked charm, grace, and aesthetic beauty. On the other hand, he was a foundational figure in the rise of French Classicism. Through his essays, letters, and work with the Académie, Chapelain helped codify the very principles that would define 17th Century French poetry.

He was a man of reason and order in a period that increasingly valued those traits. His belief in rationalism, didactic purpose, and national glory mirrored the broader currents of the Grand Siècle—the “Great Century” of Louis XIV. Though the poet failed, the thinker and critic left an indelible mark.

Legacy and Reassessment

Modern literary scholars have shown renewed interest in Chapelain, not for the quality of his verse, but for what he reveals about the cultural politics of his time. He is now seen as a bridge between Renaissance experimentation and Classical rigor—a transitional figure who helped shape the rules before others perfected them.

In today’s classrooms and literary studies, Jean Chapelain is often remembered as a footnote to greater names. Yet, his story offers essential insights into how French poetry was institutionalized and standardized in the 17th century. Without Chapelain’s advocacy for critical norms, the golden age of Racine, Boileau, and La Fontaine may have taken a very different path.

Conclusion

Jean Chapelain may not be a household name among French poets, but his contributions to 17th Century French poetry are impossible to ignore. As a poet, he was overly theoretical and rigid, unable to bring his grand ideas to life in verse. As a critic and organizer, however, he helped define the principles of French Classicism.

His failures as a poet serve to illuminate his success as a thinker. While his epic La Pucelle faded into obscurity, his influence lived on in the rules, institutions, and values that shaped one of the greatest periods in French literary history.