Louis-Nicolas Ménard (1822–1901) occupies a unique and often underappreciated space in the pantheon of 19th Century French poets. As a French poet, philosopher, chemist, and historian, Ménard stood at the crossroads of art, science, and politics. His literary works reflect a philosophical engagement with antiquity and a forward-looking vision of culture, religion, and poetic form. While not as widely known as some of his contemporaries, Ménard’s contributions to French poetry are profound and deserve critical attention. His work offers a bridge between Romantic idealism and classical formalism, situating him as a transitional figure within the broader landscape of 19th Century French poetry.

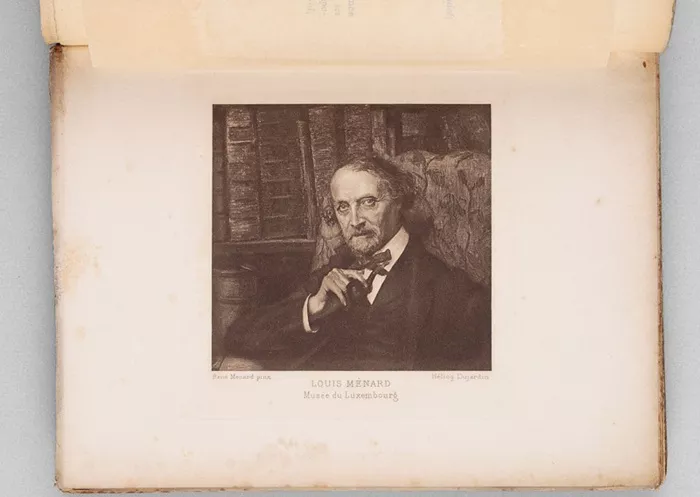

Louis Ménard

Louis Ménard was born in Paris on October 19, 1822. He was educated at two of France’s most prestigious institutions: the Collège Louis-le-Grand and the École Normale. These schools shaped his foundational knowledge of classical literature, science, and philosophy. From an early age, Ménard demonstrated a deep interest in the intellectual traditions of Greece and Rome, which would become the primary inspiration for his poetic and philosophical works.

By his early twenties, Ménard was already publishing translations of classical texts, signaling both his scholarly expertise and his literary ambitions. His translation of Prometheus Unbound, rendered from the ancient Greek, underscored his desire to revive the spirit of antiquity through the lens of modern thought. This early accomplishment revealed a philosophical commitment that would guide his entire career.

Philosophy and Poetry: A Unified Vision

Ménard did not separate poetry from philosophy. For him, both disciplines sought to uncover deeper truths about the human experience. In his poetic and prose writings, he emphasized the symbolic and spiritual power of ancient mythology. His work Poèmes (1855) is a direct result of this union between poetic form and philosophical substance. The collection draws heavily on themes from Hellenic culture, yet it speaks in a voice distinctly modern in its moral and existential questioning.

His later work, Rêveries d’un païen mystique (1876), exemplifies his synthesis of poetic intuition and metaphysical speculation. This text presents a dialogue between imagined figures—representatives of ancient and modern thought—who debate the moral implications of paganism, spirituality, and modernity. The result is neither pure poetry nor strict philosophy but a hybrid form that reflects Ménard’s broader intellectual project.

His view of ancient Greek polytheism was particularly notable. He saw it not merely as a collection of superstitions, but as a profound spiritual and philosophical framework. In his essay Du polythéisme hellénique, he argued that the multiplicity of gods symbolized different aspects of the human psyche and the natural world. To Ménard, myth and poetry were vehicles for the expression of universal truths.

Exile and Revolution

Ménard’s political ideas were closely tied to his literary and philosophical beliefs. A supporter of revolutionary ideals, he was actively involved in the upheavals of 1848 in Paris. His engagement with socialism and republicanism was not just political—it was also spiritual. He believed that a more just society could arise from a return to values rooted in both reason and myth.

In 1849, following the publication of a politically provocative pamphlet, Ménard was sentenced to prison. Rather than serve time, he fled to London, where he remained in exile for several years. This period of displacement deepened his intellectual resolve and shaped his vision of a cosmopolitan and philosophical form of French poetry.

When he returned to Paris in 1852, he resumed both his scientific and literary activities. His scientific background—especially in chemistry—fed his precision and clarity of language, even as his poetic vision became increasingly metaphysical.

French Poetry and the Classical Ideal

In the context of 19th Century French poetry, Ménard occupies a space often overshadowed by more flamboyant figures like Victor Hugo, Charles Baudelaire, and Paul Verlaine. However, Ménard’s contribution lies not in romantic excess or decadent experimentation but in the careful crafting of a poetic language rooted in classical discipline and philosophical inquiry.

He was an early precursor to the Parnassian movement, which emphasized formal rigor, objectivity, and a return to classical themes. Though never officially aligned with the Parnassians, his influence is evident in their rejection of Romantic subjectivity and embrace of aesthetic idealism. Poets such as Leconte de Lisle and José María de Heredia echoed Ménard’s devotion to antiquity and mythological themes, though they often lacked his philosophical depth.

In contrast to Symbolists like Stéphane Mallarmé, who sought to dissolve meaning in a haze of musicality and abstraction, Ménard aimed for clarity, precision, and spiritual resonance. His vision of poetry was not as a mystery to be deciphered but as a vehicle of universal truths.

Comparison with Contemporaries

To fully understand Ménard’s position within French poetry, it is helpful to compare him with the major literary figures of his age:

-

Victor Hugo was the towering figure of French Romanticism. His poetry was emotional, political, and grandiose. In contrast, Ménard offered a quieter, more meditative voice. Where Hugo appealed to the passions, Ménard appealed to the intellect.

-

Charles Baudelaire, often considered the father of modern French poetry, explored the decadent and the urban. His poems dwelt on sin, death, and ennui. Ménard, on the other hand, turned toward ancient ideals and spiritual harmony. Baudelaire sought salvation in beauty; Ménard sought wisdom in myth.

-

Stéphane Mallarmé, a key figure in Symbolism, aimed for opacity and ambiguity. Ménard, by contrast, believed in the intelligibility of poetry. He used myth not to obscure but to reveal. His classical grounding gave his work a clarity that many Symbolists eschewed.

-

Leconte de Lisle, often considered the chief of the Parnassians, shared Ménard’s love for ancient themes. However, while Leconte de Lisle’s poetry could be cold and detached, Ménard’s verse retained a quiet warmth. His passion for antiquity was not aesthetic alone; it was philosophical and spiritual.

In this way, Ménard serves as a bridge between schools and eras—a 19th Century French poet who looked backward in order to look forward.

Scientific Mind, Poetic Soul

It is important not to overlook Ménard’s scientific background. As a chemist, he was methodical and precise. These traits are reflected in his poetry, which is disciplined and deliberate. However, he never allowed science to eclipse the spiritual. In his view, science and poetry were complementary ways of understanding the world.

He believed that mythology could coexist with modern science, each offering insights into human nature. This belief placed him at odds with more materialist thinkers of his time, but it also enabled him to articulate a uniquely balanced worldview—one where reason and intuition worked together in the service of truth.

Legacy and Influence

While Louis Ménard never achieved the public fame of some of his contemporaries, his influence is quietly felt across generations of French poets and thinkers. His efforts to integrate classical wisdom into modern literature helped prepare the ground for later movements that sought to revive metaphysical and philosophical dimensions in poetry.

Philosophers and literary critics alike have admired his synthesis of poetic form and philosophical content. His work serves as a model for those who believe that poetry can still be a vehicle for wisdom, not just aesthetic pleasure.

His writings are also of enduring interest to historians of religion and philosophy. His concept of a mystical paganism—one that draws ethical and spiritual value from ancient myth without resorting to superstition—has inspired comparative religion scholars and cultural theorists alike.

Conclusion

Louis Ménard stands as one of the most intellectually rich figures in 19th Century French poetry. As a French poet, he defied the dichotomy between emotion and reason, blending myth and modernity, science and spirituality. His works invite us to consider the deeper meanings behind classical stories and to explore how these narratives continue to shape human thought.

In an age often divided between romantic emotion and cold rationalism, Ménard charted a third path—one grounded in the harmony of thought, form, and feeling. His poetry remains an essential part of French literary heritage, and his philosophical insights continue to resonate with readers seeking meaning beyond the superficial.

Louis Ménard may not be a household name, but his contribution to French poetry is undeniable. His legacy endures not only in the lines of his verse but in the timeless questions his work dares to ask: What is beauty? What is truth? What is the role of myth in a modern world?

Through such questions, this 19th Century French poet continues to speak to us today.