Phoebe Hesketh stands as a distinctive voice among 20th Century British poets. Though not as widely known as some of her contemporaries, Hesketh made significant contributions to British poetry through her lyrical sensitivity, keen observation of nature, and emotionally resonant themes. Her work reflects both personal and universal experiences, deeply embedded in the rural landscapes of Lancashire. As a British poet who often merged the domestic and the pastoral, she offers a refreshing counterpoint to the urban modernism of poets like Philip Larkin or the political engagement of W. H. Auden. This article explores Hesketh’s life, themes, style, and lasting legacy in the context of 20th Century British poetry.

Phoebe Hesketh

Born in Preston, Lancashire, in 1909, Phoebe Hesketh came from a family steeped in both science and the arts. Her father, Arthur E. Rayner, was a pioneering radiologist, while her mother was a violinist in the Hallé Orchestra. Adding a layer of political and feminist legacy, her aunt, Edith Rigby, was a renowned suffragette. This diverse cultural and intellectual environment helped shape Hesketh’s worldview and, subsequently, her poetry.

Educated at Cheltenham Ladies’ College, Hesketh was forced to leave at the age of 17 to care for her ailing mother. This early assumption of responsibility fostered a mature introspection that later found voice in her poetry. She married in 1931 and spent much of her life in the countryside of Lancashire—a setting that deeply influenced her writing.

Literary Beginnings and Development

Hesketh’s literary career began in journalism. During World War II, she worked as the Women’s Page Editor for the Bolton Evening News. This role helped her develop a concise and engaging writing style that would become a hallmark of her poetic voice. Her journalistic clarity, combined with poetic sensitivity, allowed her to write with emotional precision.

Her first collection, Poems (1939), was a modest beginning, which she later dismissed as immature. However, it was her second collection, Lean Forward, Spring! (1948), that garnered critical attention. The volume was praised for its grace and clarity, marking Hesketh as a promising talent among 20th Century British poets.

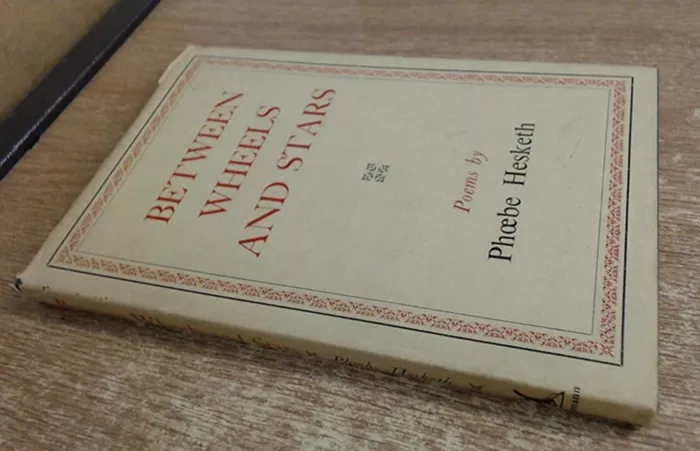

Over her lifetime, she published sixteen books, including collections of poetry, children’s literature, and autobiographical works. Some notable titles include Out of the Dark (1954), A Song of Sunlight (1974), and Netting the Sun: New and Collected Poems (1989).

Thematic Concerns

Nature and Rural Life

At the heart of Hesketh’s poetry lies an intimate relationship with nature. Her poems often describe the countryside, changing seasons, and the subtleties of plant and animal life. This attention to the natural world places her in the tradition of earlier nature poets such as John Clare and Edward Thomas, but with a distinctly 20th-century sensibility.

Unlike some of her contemporaries who explored modernity, urban alienation, or existential dread, Hesketh remained grounded in the natural and the personal. Her landscapes are not mere settings but become metaphors for emotional and spiritual states.

Women’s Experience and Domesticity

Though never explicitly feminist, Hesketh’s work subtly foregrounds women’s experiences. Poems about family, motherhood, aging, and caregiving reflect a quiet strength and resilience. In this respect, she aligns with other female British poets of the century, such as Kathleen Raine and Elizabeth Jennings, who explored similar themes with emotional depth and lyrical control.

Life, Death, and Transcendence

Hesketh’s poems often explore mortality and the fleeting nature of existence. In works such as “Geriatric Ward,” she meditates on aging and the loss of vitality, using natural imagery to offer dignity and grace to the human condition. Her handling of death is neither sentimental nor grim, but reflective and philosophical.

Style and Language

Hesketh’s poetry is marked by its clarity and musicality. She favored simple clauses and accessible vocabulary, allowing her work to resonate with a wide readership. Her style is lyrical, yet grounded, often using tight, imagistic lines to evoke mood and meaning.

She rarely experimented with radical forms or abstract language, in contrast to poets such as Dylan Thomas or T. S. Eliot. Instead, she employed traditional forms and meters, crafting verse that was both elegant and emotionally rich.

This stylistic choice aligned her more with poets such as Edward Thomas and Charles Causley than with the avant-garde. Yet it is precisely this classical restraint that gives her poems their enduring power.

Comparison with Contemporaries

Philip Larkin

Philip Larkin, one of the most prominent 20th Century British poets, is known for his bleak realism and focus on modern life’s disillusionment. While both poets wrote about mortality and the passage of time, their tones differ sharply. Larkin’s work is often cynical and ironic, whereas Hesketh’s is infused with wonder, even in the face of sorrow.

Louis MacNeice

MacNeice, another influential British poet, brought a cosmopolitan and politically conscious lens to his work. His poems reflect urban settings and international concerns, in contrast to Hesketh’s rural introspection. Where MacNeice’s style is often discursive and associative, Hesketh’s remains concentrated and lyrical.

Stevie Smith

Stevie Smith’s blend of whimsy and existential dread offers a unique comparison. While both poets address themes of life and death, Smith’s idiosyncratic voice and irony contrast with Hesketh’s more traditional, earnest approach. Nonetheless, both shared a talent for compressing complex emotions into deceptively simple forms.

Recognition and Later Life

Although Hesketh never achieved the level of fame that some of her contemporaries enjoyed, her work was well-respected. In 1956, she was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature. In 1990, she became a Fellow of the University of Central Lancashire, further affirming her importance within the canon of British poetry.

Hesketh continued writing into her later years, even as her eyesight deteriorated. Her final poems reveal a continued commitment to observing the world with precision and empathy. She died in 2005, leaving behind a rich body of work that continues to be appreciated by scholars and readers alike.

Legacy

Phoebe Hesketh’s contribution to 20th Century British poetry lies in her unwavering attention to the quiet details of life. She was not a revolutionary, nor was she part of any literary movement. Instead, she carved out her own space—a poetic world where the domestic and the natural coalesce, where emotion is conveyed through simple language and subtle imagery.

As a British poet, her work reflects a distinctly regional sensibility, yet speaks to universal themes of love, loss, and renewal. In the broader tapestry of 20th Century British poets, she provides a necessary balance: a voice of calm in a century often marked by turbulence.

Conclusion

Phoebe Hesketh may not dominate anthologies or syllabi, but her work remains a vital part of British poetry. Her poems, grounded in nature and lived experience, offer clarity and emotional depth that stand the test of time. In comparing her to other 20th Century British poets, we see the breadth and diversity of voices that defined the period.

Hesketh reminds us that poetry need not be loud to be heard. Sometimes, the quietest voices speak with the most enduring resonance. As we continue to explore the landscape of 20th Century British poetry, her work deserves recognition, study, and admiration—not only for its beauty, but for its honesty.