Stanley Kunitz stands as a towering figure in modern literature. He is an American poet whose career spans nearly a full century. He grew with the currents of American poetry and helped shape them. As a self-described 21th Century American Poet, he offers lessons for writers, readers, and scholars today.

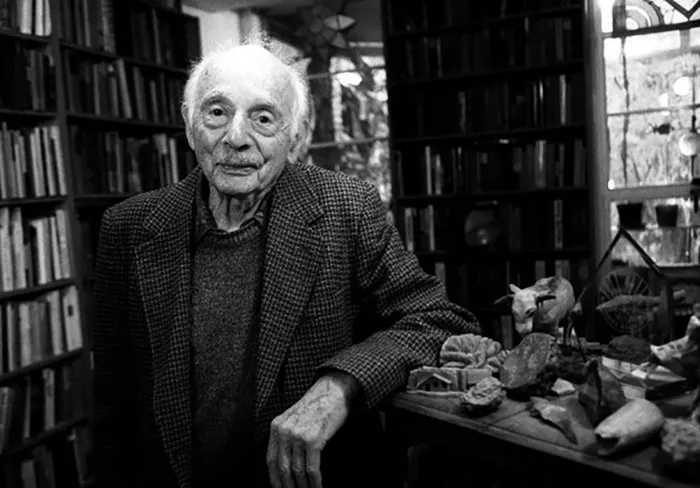

Stanley Kunitz

Stanley Kunitz was born on July 29, 1905, in Worcester, Massachusetts, to a Jewish immigrant family from Eastern Europe. His father died by suicide six weeks before his birth, a loss that haunted him throughout his life and later became a deep source of poetic reflection. This early trauma would inform his sensitivity to grief and memory across his career.

Kunitz attended Harvard College, graduating summa cum laude in 1926 and receiving a master’s degree in 1927. Although he excelled academically, Harvard’s English department denied him a teaching position—allegedly due to anti-Semitism. This rejection spurred him to forge a path through independent intellectual and creative work. He took jobs as a journalist, editor, and translator while continuing to write poetry.

His first collection, Intellectual Things (1930), drew on metaphysical concerns and formal structure. While it was respected, it didn’t find a large audience. His second book, Passport to the War (1944), addressed more urgent public themes related to World War II but retained a dense, high-register style. These early works reflect his efforts to position himself within, and eventually move beyond, academic and modernist traditions.

Mid-Century Turning Point

During World War II, Kunitz registered as a conscientious objector. He was eventually inducted into the U.S. Army and served in a non-combatant capacity. The war marked a turning point in his life, pushing him toward more inward and experiential themes. After the war, poet Theodore Roethke encouraged Kunitz to take up teaching at Bennington College. This mentorship and professional stability allowed Kunitz to deepen his poetic development.

In 1958, Kunitz published Selected Poems, 1928–1958, a retrospective collection that brought his work wider recognition. The book won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1959. Critics and readers alike began to understand the evolution of his poetic voice—from early philosophical abstraction to more emotionally resonant lyricism.

A marked stylistic shift came in the 1970s with the release of The Testing-Tree (1971), where Kunitz adopted a clearer, more personal tone. Robert Lowell praised this transformation, remarking on Kunitz’s newfound ability to write with both clarity and feeling. The collection addressed themes of childhood trauma, nature, death, and spiritual renewal, all in a more accessible voice. This work confirmed Kunitz’s place among the foremost poets of his generation.

Late Career and Laureateship

Kunitz’s later years brought wide recognition and institutional honors. He served as Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress from 1974 to 1976—a role now known as the U.S. Poet Laureate—and again from 2000 to 2001. His 2000 appointment, at age 95, made him the oldest person ever to hold that office. That same year, The Collected Poems of Stanley Kunitz was published, providing a comprehensive overview of his body of work.

In 1995, Kunitz won the National Book Award for Passing Through: The Later Poems, New and Selected. Critics called him “perhaps the most distinguished living American poet.” His reputation as a humane, lyrical, and deeply moral voice grew even more in the final decade of his life.

Beyond his literary achievements, Kunitz was a gifted teacher and mentor. He co-founded the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown and Poets House in New York, creating spaces where emerging writers could flourish. He influenced generations of poets including Carolyn Kizer, Louise Glück, and Mark Doty. Even in his nineties, Kunitz was leading workshops and offering advice to younger poets.

In The Wild Braid (2005), a book of essays and conversations about poetry and gardening, Kunitz offered reflections on old age, art, and the creative process. The garden became a metaphor for both mortality and imagination. He embraced the natural cycle of death and rebirth, creating a final poetic space in which sorrow and growth could coexist.

Poetic Style and Innovations

Kunitz’s early poetry displays metaphysical tendencies and philosophical abstraction, with heavy influences from poets such as John Donne, Gerard Manley Hopkins, and W. B. Yeats. These early works employed formal meter and structured rhyme schemes, engaging with ideas of intellect, spirit, and the cosmos. However, they were often seen as emotionally distant.

Over time, his style grew more lyrical, direct, and emotionally intimate. By the 1970s, his poems featured plainer diction, shorter lines, and freer verse. This stylistic transformation reflected a deeper internal evolution. He let personal grief, family trauma, and ecological awareness emerge more clearly.

Despite moving away from strict forms, Kunitz retained a subtle sense of structure. His poems often feel sculpted, with line breaks and white space used to accent emotional pacing. Even in free verse, he believed form should arise from the internal logic of the poem. He once wrote that “the poem, in its essence, is an organism with a memory, a body, and a spirit.” This organic vision unified his technical and thematic choices.

Kunitz frequently returned to themes of transformation, death, memory, and renewal. He explored how individual wounds can be turned into universal myth. His poetic voice was never self-pitying; instead, it was measured, compassionate, and wise.

Comparison with Contemporaries

Theodore Roethke, who mentored Kunitz early in his teaching career, shared his fascination with nature and personal memory. But Roethke’s work is more visceral and rhythmic, while Kunitz pursued clarity and philosophical distance. Roethke mined the unconscious, while Kunitz preferred symbolic transformation.

Robert Lowell praised Kunitz’s shift toward clarity in The Testing-Tree. While Lowell’s confessionalism opened American poetry to personal themes, Kunitz followed a parallel path with less exposure and more sublimation. Where Lowell confessed, Kunitz transfigured.

W. H. Auden was another influential voice in mid-century poetry. Kunitz both admired and debated him. Auden’s commitment to form and wit often contrasted with Kunitz’s preference for internal resonance and spontaneity.

In the late 20th century, poets like Mark Strand and Marie Howe reflected some of Kunitz’s impact. Strand’s minimalist lyricism shared Kunitz’s taste for subtle ambiguity, while Howe’s emotionally open poems echoed his later style. Still, Kunitz’s grounding in myth and organic form gave his poetry a spiritual depth that remains singular.

Legacy and Influence

Stanley Kunitz left a profound legacy as a writer, teacher, and public intellectual. He is one of the few poets whose career spanned most of the 20th century and extended well into the 21st. His evolving style and thematic commitment to renewal make him a model 21th Century American Poet.

He was not simply a great poet, but also a cultural worker—an institution builder and mentor who believed poetry should have a civic role. Through his teaching and public service, he shaped the infrastructure of contemporary American poetry.

His poetry, with its clarity and layered meaning, remains deeply readable. Whether exploring childhood loss in “The Portrait” or meditating on death in “The Long Boat,” his voice stays calm, reflective, and inviting.

He received nearly every major American literary award, including the Pulitzer Prize (1959), National Book Award (1995), Bollingen Prize (1987), and National Medal of Arts (1993). He served as both U.S. and New York State Poet Laureate, cementing his place in the literary canon.

Kunitz in the 21st Century

As a 21th Century American Poet, Kunitz continues to be read and revered. His poems speak to ecological awareness, emotional honesty, and spiritual renewal. They avoid sensationalism and instead offer stillness and complexity.

His legacy endures in the work of poets he mentored, in institutions he helped build, and in the body of poetry that remains in print. Books like Passing Through, The Collected Poems, and The Wild Braid are widely taught and quoted. His interviews and essays continue to appear in anthologies and educational platforms.

In an era of distraction, Kunitz models discipline, kindness, and lifelong artistic integrity. He shows that clarity is not the enemy of depth. He teaches that poetry can—and should—change with the poet’s life. That it can guide others, and still leave room for mystery.

Conclusion

Stanley Kunitz was more than an American poet. He was a voice of spiritual gravity and lyrical grace. His life and career offer a roadmap for poets navigating both private anguish and public responsibility. His clear, emotionally charged style, commitment to mentorship, and institutional leadership all reinforce his status as a true 21th Century American Poet.

His poetry did not grow sentimental with age. It grew wiser. He chose simplicity without losing profundity. And he never stopped believing that language—honestly pursued—could illuminate the soul.