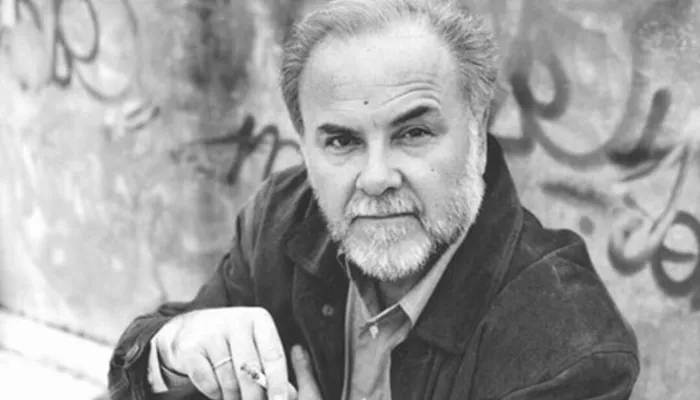

Greek poetry in the 20th century presents a complex and rich tapestry of voices that reflect the turbulent history and diverse cultural identity of Greece. Among these voices, the work of Michalis Ganas, born in 1944 in the region of Epirus, stands out for its emotional clarity, lyrical precision, and deep connection to memory and place. Though he is often considered a poet of the late 20th century, Ganas belongs to a lineage of Greek poets whose work was shaped by war, exile, and transformation. His poetry offers a unique perspective that balances personal grief with collective experience.

Historical Context and Literary Landscape

To understand Ganas’s contribution, it is essential to explore the broader literary context of 20th century Greek poets. This was a period of significant upheaval in Greece—marked by the Balkan Wars, the Asia Minor Catastrophe, World War II, civil war, dictatorship, and eventual democratization. These events influenced generations of poets, who responded to them in varied ways.

The early 20th century was defined by the emergence of modernism in Greek poetry. Poets like Kostas Karyotakis and Napoleon Lapathiotis introduced a darker, introspective tone into Greek verse, often with themes of alienation and existential despair. In the mid-century, figures like George Seferis and Odysseas Elytis brought Greek into international prominence, both winning Nobel Prizes. Their work, heavily influenced by modernist aesthetics and classical heritage, combined metaphorical density with political nuance.

Michalis Ganas entered the poetic scene later, in the post-junta years, a time of literary renewal and re-examination. His voice, however, was distinct from those of his predecessors. He did not aim for grand allegory or historical synthesis. Instead, his poetry found its strength in minimalism, emotional honesty, and a deep engagement with language and tradition.

Early Life and Influence of Epirus

Born in 1944 during the final year of Nazi occupation and just before the outbreak of the Greek Civil War, Ganas experienced early trauma and displacement. He spent his childhood in the region of Epirus, near the Greek-Albanian border—a mountainous and culturally rich area known for its folk traditions, polyphonic music, and oral storytelling. These early experiences left a deep imprint on his poetic sensibility.

In 1947, during the height of the civil war, Ganas’s family was forced into exile in communist Albania. The memory of exile, the sense of being uprooted, and the longing for return recur throughout his poetry. These themes place him in dialogue with other Greek poets of trauma and displacement, such as Yannis Ritsos, though Ganas’s style is far more restrained and lyrical.

Language and Poetic Style

Michalis Ganas’s poetry is notable for its simplicity and musicality. His language is pared down, often echoing the rhythms of folk songs or traditional laments. He avoids complex metaphors or rhetorical flourishes. Instead, his lines are clean, direct, and deeply resonant. This simplicity is not a lack of sophistication, but a deliberate aesthetic choice that connects his work to the oral traditions of his native Epirus.

While Seferis and Elytis used symbolism and myth to grapple with national identity, Ganas worked on a smaller scale, focusing on the family, the village, and the self. His poems often deal with everyday objects—a stone, a window, a tree—but these objects are invested with memory and emotion. This attention to the material world and its symbolic resonance aligns him with poets such as Nikos Karouzos, though again Ganas’s tone is more subdued and melancholic.

Key Works and Themes

Ganas published his first collection, Elliniki Demosia Teleorasi (Greek Public Television), in 1978. The title itself signals a tension between tradition and modernity, between the oral and visual, between private memory and public representation. The poems in this collection are understated but emotionally charged, often meditating on silence, absence, and loss.

One of his most celebrated collections, Parathyra Me Thea Ston Kosmo (Windows with a View of the World), deepens these concerns. The window becomes a recurring image—at once a frame and a barrier, a metaphor for both openness and confinement. Through this image, Ganas explores the poet’s position in society, caught between observation and participation.

His 1993 collection, Agapi Den Einai Na Legeis (Love Is Not to Speak), marked a mature phase in his poetic journey. In these poems, love and death are intertwined, as he reflects on personal loss, the passage of time, and the impossibility of return. His verse, though minimal, carries an emotional weight that is both intimate and universal.

Another important theme in Ganas’s work is the relationship between language and memory. He often writes about the silences within language—the words that cannot be spoken, the memories that resist narration. This theme aligns him with the broader postmodern concerns of late 20th century literature, though Ganas never fully embraces postmodern playfulness. His tone remains elegiac, sincere, and rooted in lived experience.

Comparison with Contemporaries

To better appreciate Ganas’s unique contribution, it is helpful to compare his work with other Greek poets of the 20th century. For example, Yannis Ritsos—one of the most prolific and politically engaged poets of modern Greece—used poetry as a tool of resistance. His long poems, such as Epitaphios and Romiosini, are filled with collective memory and revolutionary hope. Ganas, by contrast, turns inward. His poetry does not seek to mobilize but to mourn. Where Ritsos is declarative, Ganas is contemplative.

Another point of comparison is Kiki Dimoula, a poet known for her complex syntax and philosophical depth. Dimoula often explores themes of absence, identity, and the limits of language, much like Ganas. However, her style is more cerebral and ironic. Ganas remains emotionally grounded, more concerned with the heart than the intellect.

In the realm of lyrical expression, Ganas may also be compared to Tasos Livaditis, especially in his later work, which is marked by a similar tenderness and melancholy. Both poets write about solitude, the passage of time, and the fragility of human connection. Yet, Ganas’s work is even more stripped down, often closer to song than statement.

Influence of Music and Oral Tradition

One of the most distinctive features of Michalis Ganas’s poetry is its connection to Greek oral traditions and music. He has collaborated with composers, and many of his poems have been set to music. This relationship with song ties him to the long tradition of Greek poetry being performed and heard, not just read.

The influence of folk laments, in particular, is evident in his cadence and tone. In Epirus, the mirologia—traditional mourning songs—express grief in communal settings. Ganas adapts this form for the personal sphere. His poems often read like laments for lost time, lost family, and lost homelands. Yet, despite their sorrow, they never descend into despair. There is always a note of resilience, of holding on through memory and language.

Reception and Legacy

While not as internationally known as Seferis or Elytis, Michalis Ganas is highly respected within Greek literary circles. He has received several national awards, and his work is taught in schools and universities. His poetry resonates particularly with younger generations of Greek poets, who find in his work a model of emotional sincerity and formal restraint.

Ganas has also worked as a translator and scriptwriter, further contributing to Greek cultural life. His translations from Albanian and his involvement in television and film demonstrate his commitment to bridging traditional and contemporary forms.

His legacy lies in his ability to articulate the quiet sorrows of ordinary people. In a century filled with noise—war, ideology, revolution—Ganas offers a poetry of silence. He teaches us that Greek poetry need not always be grand or historical to be meaningful. Sometimes, the softest voice carries the deepest truth.

The Place of Ganas in 20th Century Greek Poetry

As we consider the panorama of 20th century Greek poets, Michalis Ganas occupies a special place. He represents a turn away from myth-making and nation-building toward introspection and lyricism. His work bridges the old and the new, the rural and the urban, the traditional and the modern.

While many poets of his generation engaged directly with political themes, Ganas chose the path of inner exile. His focus on the individual’s emotional landscape does not negate historical consciousness; rather, it reframes it. The trauma of exile, for instance, becomes a metaphor for emotional estrangement. The landscape of Epirus becomes a symbolic terrain for memory and identity.

In this way, Ganas expands the possibilities of Greek poetry, proving that lyricism and subtlety have as much place in the poetic canon as political fervor or mythic resonance. His work challenges us to listen more carefully—to pay attention to the silences between words, the spaces between memories.

Conclusion

Michalis Ganas is a vital voice among 20th century Greek poets. His poetry, rooted in the traditions of Epirus and shaped by the experiences of war and exile, offers a powerful meditation on loss, memory, and love. Through simple language and lyrical form, he has crafted a body of work that speaks to the universal human condition while remaining deeply Greek.

In comparison with his contemporaries, Ganas’s work is more intimate and subdued, yet equally profound. He reminds us that poetry need not shout to be heard. Sometimes, the quietest voice—the voice of a child displaced, a lover in mourning, a poet at his window—can leave the most lasting impression.

As readers continue to discover and rediscover Greek poetry, the work of Michalis Ganas will remain a touchstone of emotional honesty and lyrical beauty. His poems are not monuments; they are paths—narrow, winding, and tender—leading us back to what it means to feel, to remember, and to belong.