Friedrich Hölderlin (1770–1843) stands as a seminal figure in the history of German poetry. Though often overshadowed by contemporaries like Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Friedrich Schiller, Hölderlin’s work profoundly shaped the evolution of poetic expression in Germany and beyond. A 19th Century German poet with deep philosophical and spiritual insights, Hölderlin fused the ideals of Greek antiquity with the restless, searching soul of Romanticism.

This article explores the life, poetic vision, and enduring legacy of Friedrich Hölderlin. By examining his style, themes, and influence, we uncover the uniqueness of his contribution to German poetry. In addition, comparisons with other 19th Century German poets will help situate Hölderlin in his literary and cultural context.

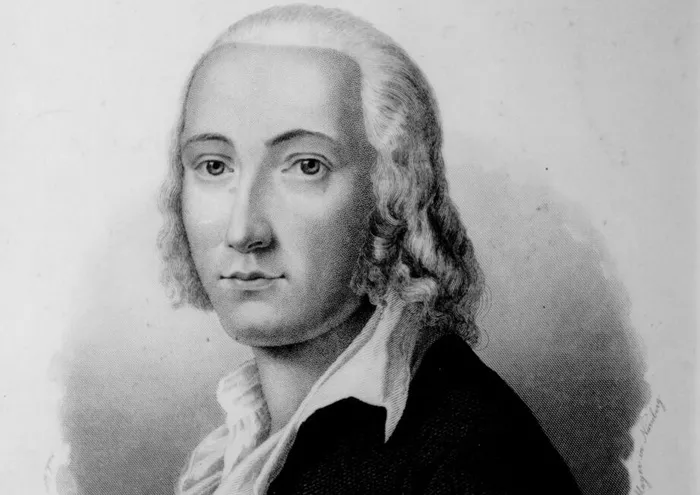

Friedrich Hölderlin

Friedrich Hölderlin was born on March 20, 1770, in Lauffen am Neckar, in the Duchy of Württemberg. His father died when he was young, and his mother enrolled him in religious schools with the hope he would enter the clergy. He studied at the Tübinger Stift, a Protestant seminary, where he became close friends with two of Germany’s greatest minds: Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel and Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling.

At the Tübinger Stift, Hölderlin immersed himself in classical literature, theology, and philosophy. The influence of ancient Greek texts would become foundational to his poetic vision. Even at this early stage, Hölderlin distinguished himself as a writer with a unique voice.

Philosophical and Poetic Foundations

Hölderlin’s poetry reflects a synthesis of Enlightenment rationalism and Romantic yearning. He admired the balance and harmony of Greek antiquity and believed that poetry should restore a lost unity between humanity and nature. Influenced by philosophers such as Spinoza, Kant, and later Fichte, Hölderlin viewed the world as an organic whole.

His philosophical leanings did not make his verse obscure. Instead, his poems present profound truths through concrete, lyrical images. His use of classical allusions, combined with personal and spiritual longing, created a rich poetic landscape.

The Impact of Ancient Greece

Ancient Greece played a central role in Hölderlin’s poetry. He saw Greek culture as the pinnacle of human achievement, a golden age when man, nature, and the divine were united. In poems such as “The Archipelago” and “The Death of Empedocles”, Hölderlin evokes this harmonious past as a contrast to modern fragmentation.

For Hölderlin, Greece was not only a source of aesthetic inspiration but also a model for political and spiritual renewal. His interest in figures like Empedocles and Sophocles reflected his desire to merge philosophical depth with poetic clarity.

Romanticism and Nature

As a 19th Century German poet, Hölderlin belonged to the early Romantic tradition, though he resisted easy categorization. Unlike many Romantic poets who idealized nature sentimentally, Hölderlin saw nature as sacred and immanent. His poems speak of rivers, mountains, and celestial phenomena not just as beautiful images, but as manifestations of the divine.

In “Patmos”, one of his most celebrated poems, Hölderlin writes, “But where danger is, grows / The saving power also.” This famous line encapsulates his belief in the dialectic between suffering and salvation, a theme common in Romantic and post-Romantic thought.

Language and Form

Hölderlin’s language is both elevated and intimate. He employed traditional meters, including the Pindaric ode and elegiac couplets, but often modified them in innovative ways. His style combined clarity with mystery, simplicity with depth.

His late hymns and odes often display a fragmented syntax, reflecting his mental decline but also introducing a modernist quality. This “late style” has been influential on poets such as Paul Celan and philosophers like Martin Heidegger.

Mental Decline and Isolation

Tragically, Hölderlin’s life was marked by psychological instability. By 1806, after a period of intense poetic activity, he was declared mentally unfit and was institutionalized. He spent the final 36 years of his life in a tower in Tübingen under the care of a carpenter named Zimmer.

Despite his seclusion, Hölderlin continued to write. These later works, sometimes labeled as “tower poems,” exhibit a childlike clarity and a profound spiritual tone. Though less polished, they are deeply moving and bear witness to the resilience of poetic vision in the face of suffering.

Comparison with Contemporaries

Hölderlin’s work can be fruitfully compared with other 19th Century German poets, including Goethe, Schiller, and Novalis.

- Goethe, the quintessential German poet, was concerned with balance, humanism, and the integration of art and science. His poetry was rational and universal.

- Schiller shared Hölderlin’s interest in Greek antiquity but was more politically engaged. His poetry often addressed freedom and ethical dilemmas.

- Novalis was more mystical and idealistic. While Hölderlin’s mysticism was rooted in nature and classical forms, Novalis emphasized the inner, imaginative world.

Compared to these figures, Hölderlin stands out for his philosophical rigor and spiritual intensity. His fusion of metaphysical longing with concrete imagery gives his work a distinctive depth.

Influence on German Poetry and Philosophy

Though largely unrecognized during his lifetime, Hölderlin’s influence has grown steadily since the 20th century. He is now considered one of the foundational voices in modern German poetry.

Philosophers such as Martin Heidegger saw in Hölderlin a poet of Being, someone who articulated the sacred essence of existence. Heidegger’s lectures on Hölderlin have been crucial in re-evaluating the poet’s work.

Likewise, poets like Rainer Maria Rilke, Paul Celan, and Ingeborg Bachmann have drawn inspiration from Hölderlin’s vision. His combination of lyricism, philosophy, and spiritual searching continues to resonate.

Key Themes in Hölderlin’s Poetry

Unity with Nature

Hölderlin believed in an original unity between man and nature, now lost but retrievable through poetry. Nature is not passive in his poems; it is alive, speaking, divine.

Divine Absence and Longing

A recurring theme is the absence of the gods and the longing for their return. This reflects both religious doubt and spiritual hope.

Time and Eternity

His poems often explore the tension between transient human life and eternal truths. The river is a common symbol, representing both change and continuity.

Homeland and Exile

Though deeply rooted in German soil, Hölderlin often wrote of exile, both literal and spiritual. This duality gives his work a poignant, universal appeal.

Representative Poems

“Bread and Wine”

This poem explores the absence of the gods and the role of the poet in a secular age. It asks what remains when divine presence recedes.

“The Rhine”

Here, Hölderlin turns to a German river as a symbol of national and spiritual identity. The poem blends natural beauty with metaphysical yearning.

“To the Fates”

In this short but powerful poem, the speaker pleads for just one more year to complete his work. It expresses both vulnerability and defiance.

Reception and Legacy

Hölderlin was neglected in his time. His complex style and psychological breakdown made him a marginal figure. Yet modern critics now view him as a visionary. The 20th century brought renewed interest, particularly among existentialist and phenomenological thinkers.

Today, he is recognized not only as a 19th Century German poet of rare sensitivity but also as a prophet of the modern condition.

Conclusion: Hölderlin’s Enduring Relevance

Friedrich Hölderlin remains one of the most profound voices in German poetry. As a 19th Century German poet, he bridged the ancient and the modern, the sacred and the secular, the philosophical and the lyrical. His poetry invites us to contemplate our place in nature, the role of the divine, and the power of poetic language.

In a fragmented world, Hölderlin calls us back to unity—not as a nostalgic dream, but as a living possibility. His legacy endures not just in literature, but in the hearts of all who seek meaning through words.